BY PAT COSGROVE CACTUS WRITER photos added by Billy Dale

Drop the word “pain” in the presence of an athlete, and indubitably a shudder or flash of recognition was stirred deep into the heart. Pain was a phenomenon that for centuries has gone hand-in-hand with competition.

For most athletes, mere participation in a sport requires an unavoidable physical and psychological confrontation with pain that could rarely be avoided. Moreover, every sport has its injuries, with the accompanying sensations rendering an athlete considerably less effective or even non-functional in competition. From the rough extreme of football, with the possibility of a muscle pull to spinal cord severance, to a speed and precision game such as tennis, where the elbow was particularly susceptible, it was a straightforward, crystal clear maxim: sports begat injury and injury begat pain.

Most athletes quickly grew accustomed to dealing with the pain inherent in their sport. But the effects on performance were highly diverse. An injury debilitation in one sport could have little or no impact on play in another athletic contest. For example, football players have been known to stay in battle with broken bones set shielded with devices designed for athletes by doctors. Patched and protected, participation could continue with little or no loss of effectiveness. Yet, in a game such as baseball, an intimidating pitcher or a powerful slugger might be worthless by a mere blister on the fingertip.

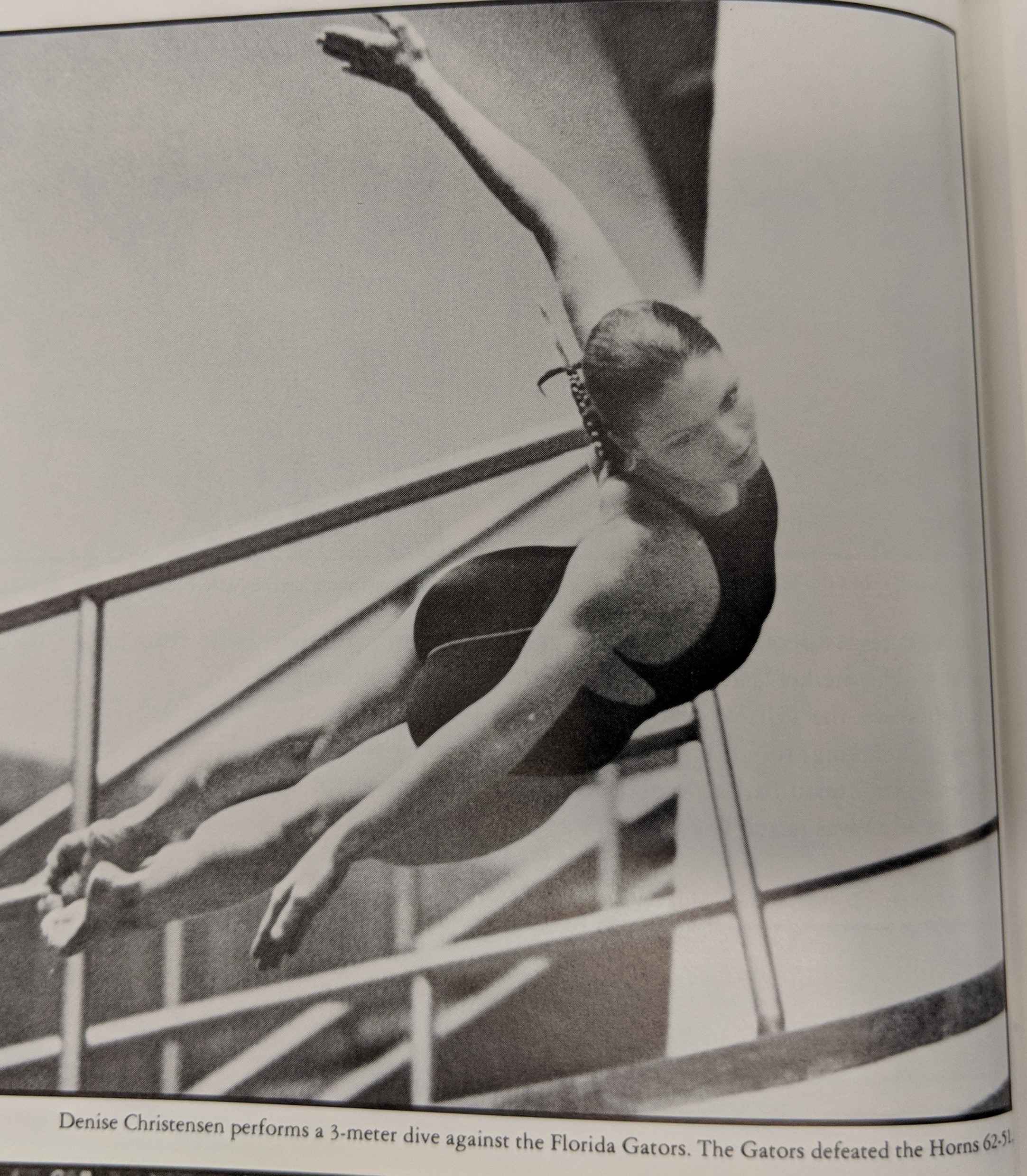

In a year filled with competitive ups and downs, many Longhorn athletes butted heads with the play-with-pain menace. Diver Denise Christensen sustained a fractured vertebra in her lower back in 1981 which kept her out of training for nine months. In her attempt to get back into shape, the pain was a major obstacle. “It was hard to start doing things again,” she explained. “I was really cautious and somewhat afraid.” As she progressed, it was pain that continued to cause her problems. “I never knew if I was overdoing it,” she said. In spite of the pain, she just kept “testing it.” When the first meet rolled around, her main concern was blocking everything out, including the discomfort. “Because of the high level of competition, you must just block it out. You know if the dive is a good one, you won’t be hurt again,” Christensen said.

“If you want to play in this league, Wilson, you’ve got to learn to play with pain!”

Bob Clary, a three-year letterman in track, grappled with minor but painful injuries over several seasons before bowing to their nagging presence. “Track is funny,” he said, “you can hardly play with even the slightest injury. The level of competition is that close.” Clary did what he could by slacking off during workouts to save himself for meets. But in the long run, he couldn’t regain a full bill of health. He summed it up very simply, saying “In track if you’re hurt, you shouldn’t be performing.”

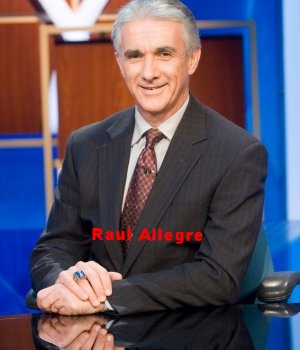

The Longhorn football team had its share of imposing physical performances in the face of extreme pain. Placekicker Raul Allegre turned in one of his key outputs of the season after a considerable struggle just to make the game. Completely down with bronchitis before the Houston game, he spent the entire day resting in bed. However, as the game got underway, “I just forgot about it,” he said. Allegre booted two crucial field goals enabling the Horns to gain a 14-14 tie. He spent the next four days in the Student Health Center.

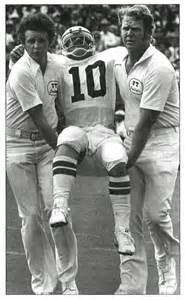

Rick McIvor

Athletes continued to compete in the face of pain because they despised the thought of sitting out or felt it was a part of the game. “You just suck it up,” said Rick McIvor, Longhorn quarterback.

Perhaps the most heart-breaking injuries of the year occurred to defensive lineman Kenneth Sims and key forward Mike Wacker. Sims was out for the season and with his injury went all hopes for the Heisman Trophy. After Wacker underwent crucial knee surgery, the previously undefeated basketball team skidded to a halt, dropping 11 of the last 13 games.

1980s Rodney Tate becomes the only Oklahoman to letter at UT since 1893.

Longhorn tailback Rodney Tate held a decidedly upbeat view on the haunting pain associated with athletics. After suffering a severe thigh bruise against Texas Tech, he spent several days in the Student Health Center and then returned to action in considerable pain. “The main thing is to forget about it,” he said. “The first time you get the ball, you’ll be thinking about it, but once you’ve been hit, you’ve got to get right up again. To keep getting up after the knocks you’ve got to concentrate,” Tate said.

Rodney Tate’s attitude reflected a personal philosophy on life; “ To be successful, in football and in life, nothing is going to be easy. Playing with pain is part of the game.”

Comments below were added by Billy Dale to expand on Pat Cosgrove’s article.

Why do athletes play with pain?

In addition to Pat Cosgrove’s observation of how and why players play through the pain, I would like to add that the possibility of losing a starting position on the team is another key motivator to play hurt.

There is an article on the TLSN site that deals with how some people just have a higher threshold of pain in their genes. Ragan Gennusa’s successful struggle to overcome pain is very inspiring.

“ I don’t want the coaches to know they can get along without me.”

There is a story told by author and former Longhorn football player R.E. Peppy Blount's book titled Mamas, don’t let your babies grow to play Football which occurred during Coach Bible watch. Blount said the Bible never played injured players so many chose to play hurt and not tell him. In the 1938 game, Nelson Puett made a touchdown to defeat the Aggies. It was the only victory for the longhorns that year. Watching the films in a dark room the next day with the player’s Coach Bible criticized Puett for carrying the ball in the arm closest to the tacklers. Bible says “why didn’t you have the ball under the other arm?” Puett says “the other arm was broken.” Coach Bible shocked turned on the lights in the film room and there sat his halfback with his left arm in a sling.