Jan Todd’s night with Johnny Carson

Terry Todd’s Documentary

How Two Powerlifters Founded One of UT’s Most Unique Places

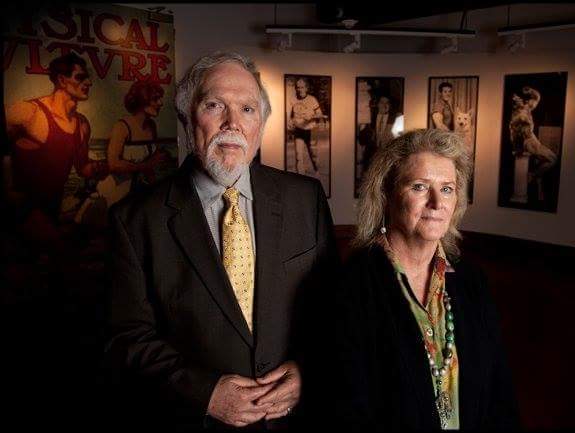

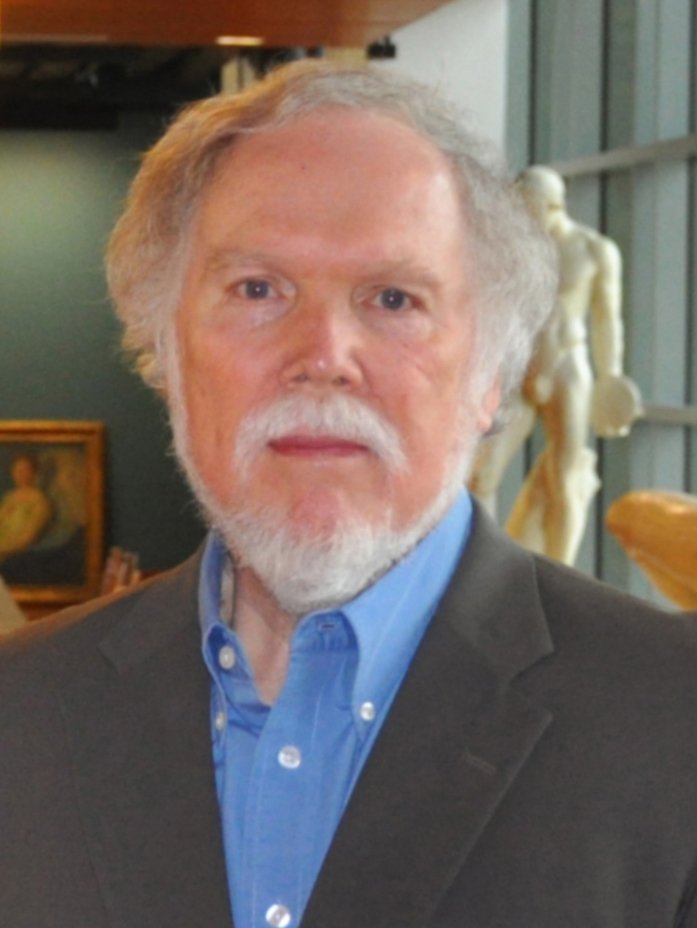

Jan Todd has a Doctor of Philosophy PH.D. American/U.S. studies/civilization for U.T. and she is a professor and Director of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center of the University of Texas at Austin. Her husband, Terry Todd, passed away in July of 2018. His biography is below.

Jan Todd continues to add value to Terry’s Legacy while continuing to add to her own impressive Legacy.

Terence (Terry) Todd—Writer, academic, journalist, champion lifter, coach, sport promoter, founder of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports at the University of Texas at Austin, and Director of the Arnold Strongman Classic, died in Austin, Texas, on Saturday, July 7, 2018.

Todd touched and helped reshape nearly all aspects of the field of strength training, brought the study of strength into academic respectability, and particularly helped create the modern sport of Strongman. He was involved in the birth and development of both men's and women's power lifting, personally coached two of the strongest men in history—Bill Kazmaier and Mark Henry (and his wife Jan Todd, a pioneer in women's power lifting), and was famous for his encyclopedic knowledge of strength history and his richly detailed, humorous stories. Todd also played a particularly important role in debunking the belief that lifting weights would make one "musclebound."

Todd's first serious sport was tennis, which he learned from his father and on the public courts at Little Stacy Park in South Austin. He played varsity tennis at Travis High School, and lettered in tennis at The University of Texas under Coach Wilmer Allison. After his high school graduation in 1956, however, he began weight training—at first simply to make his left arm as large as his dominant tennis arm—but then, as his interest in the capacity of weight training to build strength and muscle grew, he began full-body training and was soon playing varsity tennis weighing as much as 235 pounds. Coach Allison, like most coaches in the 1950s, warned Todd that lifting would hurt his tennis game and make him musclebound, a fact Todd intuitively knew then—and thousands of coaches know today —was simply not true. Todd finally gave up his scholarship rather than continue to hear about his body weight and decided to explore his strength potential.

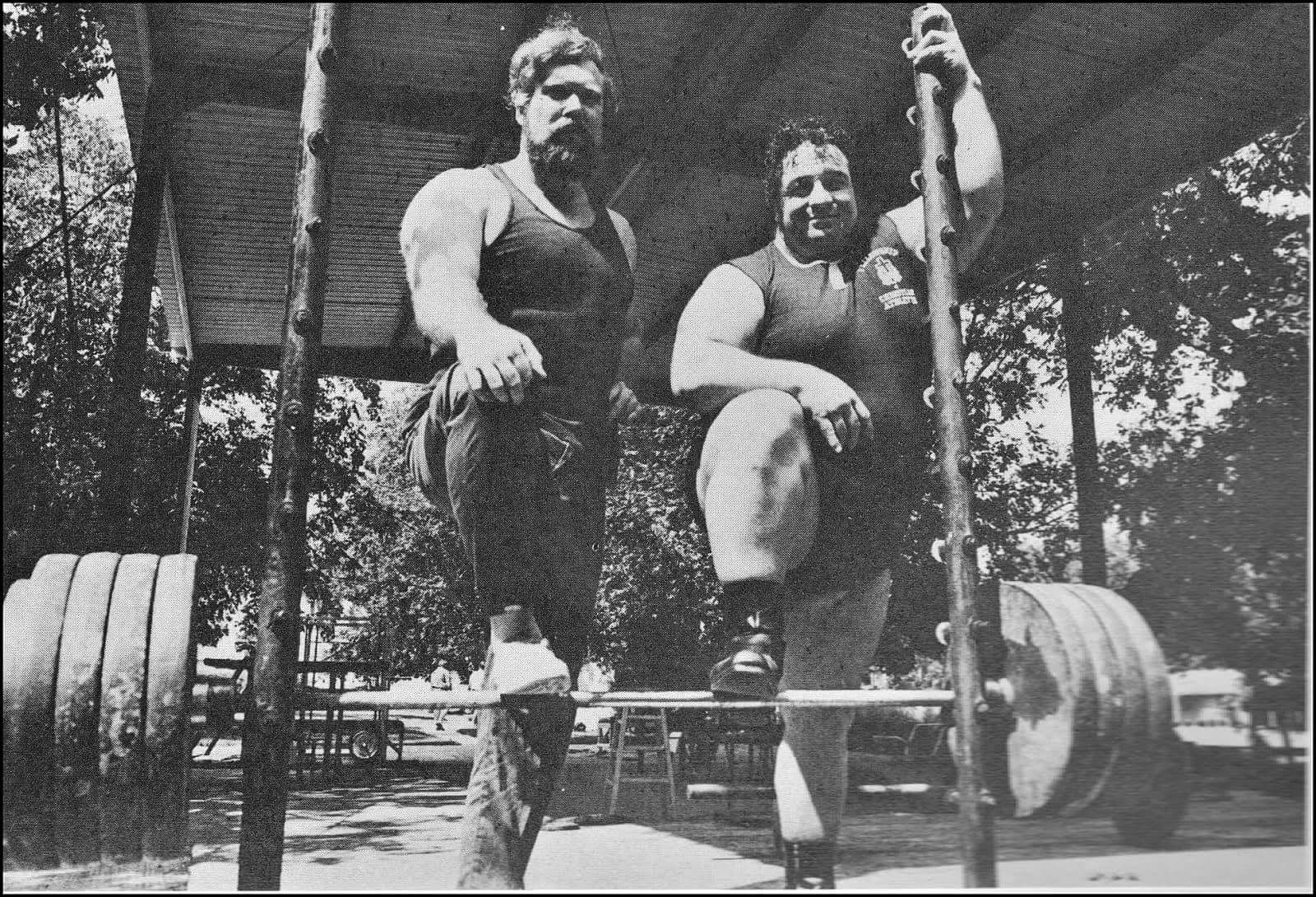

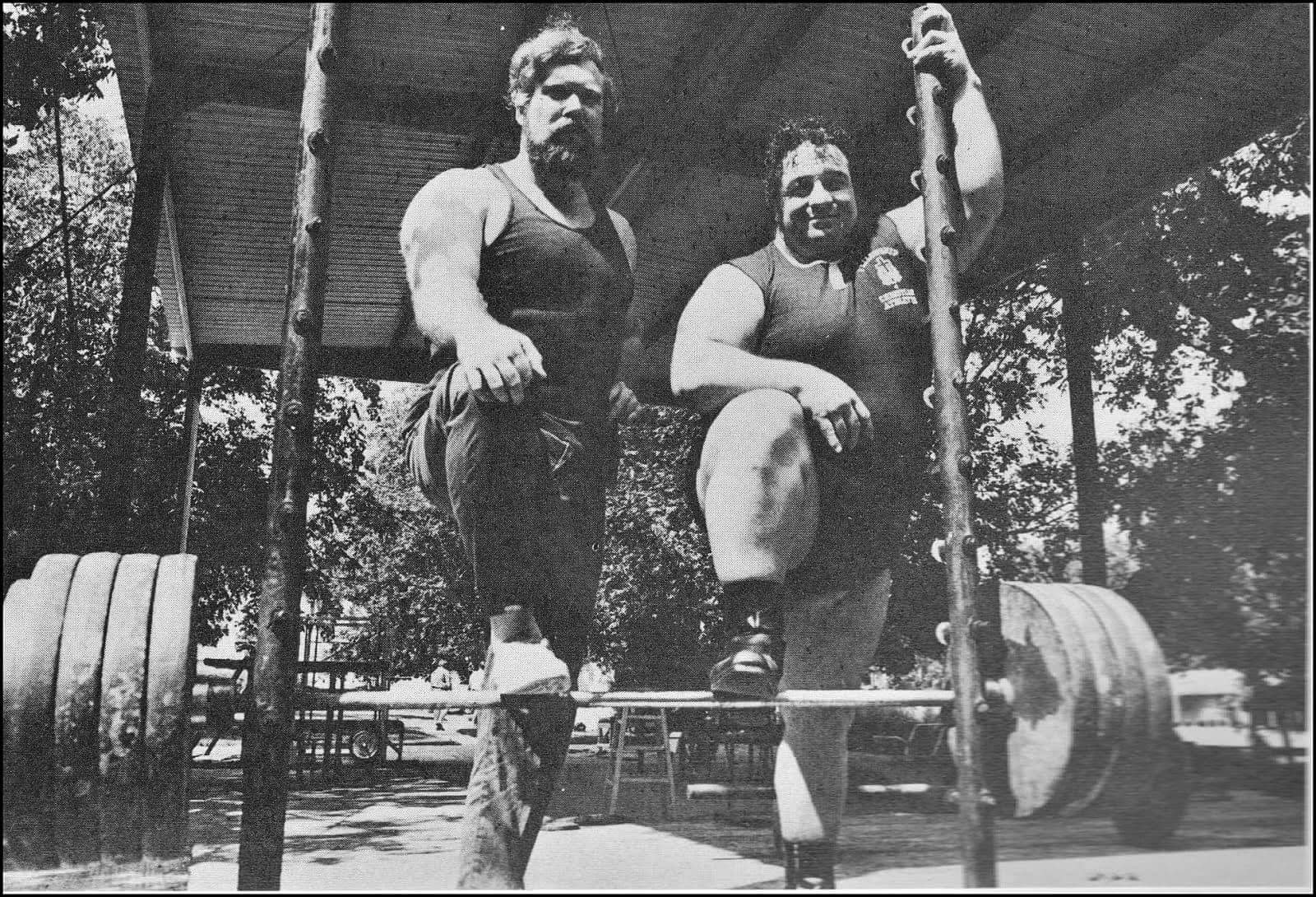

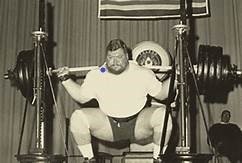

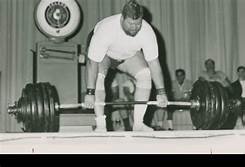

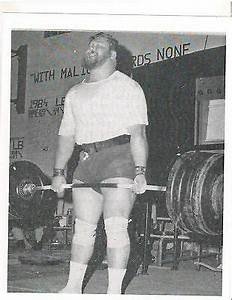

After receiving his B.A. in English from U.T. Austin in 1961, Todd began working on a doctorate in the interdisciplinary History and Philosophy of Education program and used his graduate years as a time to weight train seriously. By 1963, when he won his first major title—the AAU Junior National Weightlifting Championships—he weighed 300 pounds. He then turned to power lifting and won the first men's national championships in 1964, and, in 1965, the first official Senior Nationals in the sport. Todd was the first man to squat 700 pounds and the first man to total 1600, 1700, 1800, and 1900 pounds in power lifting. He set numerous American records, and his best official lifts were: a 720-pound squat, a 515-pound bench press, and a 742-pound dead lift. Todd retired from competition in 1967 and reduced his body weight by returning to tennis which he played for many more years.

Todd received his doctorate from the University of Texas in 1966, writing one of the first historical dissertations on the subject of resistance training. In the mid-1960s, he moved to York, Pennsylvania, and worked as managing editor of Strength & Health magazine while still a doctoral student. Following graduation, in 1966, he began his academic career at Auburn University before moving to Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, in 1969. During this early phase of his career, Todd's academic focus was not on sport or strength training, but rather on the problems faced by America's schools. At Mercer, he founded the African-American Studies program in 1969, and ran a series of summer seminars that brought together the major intellectuals working to solve the problems of American schools in the 1970s. Educational theorists John Holt, James Herndon, and Edgar Friedenberg became life-long friends. In 1973, when Todd married Janice (Jan) Suffolk, Jim Herndon served as best man at their wedding. Edgar Friedenberg, then a main reviewer for the New York Review of Books and perhaps the most important public intellectual in the school reform movement of the early 1970s, played the pivotal role in Todd's joining the faculty at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1975.

In Nova Scotia, Todd's interest in strength and powerlifting became more central to his academic focus in part because his wife Jan was setting world records in powerlifting. In 1977, after Sports Illustrated profiled her in an article entitled "The Pleasure of Being the World's Strongest Woman," the Todds were invited to New York to make several TV appearances and visit the Sports Illustrated offices. That visit resulted in an assignment from SI for Todd to write an article about champion arm wrestler, Al Turner. Once completed, more assignments for SI followed, and among the most notable are his 1982 profile of Herschel Walker, "My Body's Like an Army" that Atlanta mayor Andrew Young arranged to distribute to thousands of Atlanta school children; his 1981 article on pro wrestler Andre the Giant that was discussed in the 2018 HBO documentary Andre the Giant (in which Todd also appears); and his 1983 "The Steroid Predicament," regarded as one of most influential articles on doping and sport of the 1980s. During his lifetime, Todd authored more than 500 articles in scholarly and popular magazines. He also authored or co-authored seven books including Philosophical Considerations of Physical Strength (2010 with Mark Holowchak), Herschel Walker's Basic Training (1985 and 1989 with Herschel Walker), Lift Your Way to Youthful Fitness (1985 with Jan Todd); Inside Powerlifting—the first book on the sport of powerlifting (1978); and Fitness for Athletes (1978). His final book, Strength Coaching in America: A History of the Most Important Sport Innovation of the Twentieth Century (with Jason Shurley and Jan Todd) will be published in 2019. He and Jan also began the important academic journal Iron Game History: The Journal of Physical Culture in 1990 and have edited it for the past 28 years.

In 1979, Todd returned to Auburn where he established the National Strength Research Center at Auburn University, a training facility in which top-level strength athletes like Bill Kazmaier, Lamar Gant, and Jan Todd interacted with exercise scientists to help advance strength science. As his reputation as an expert on strength grew, Todd was often asked to do color commentary on TV and worked for several years as a "consultant on strength sports" for CBS television. Todd was also involved with the early TWI Worlds' Strongest Man Competitions both as a broadcaster and as a strength expert, and, in 1980, 1981, and 1982 he promoted his own "Strongest Man in Football" television shows.

Terry and Jan moved back to Austin in 1983 where he joined the faculty of the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education. With them came more than 300 boxes of books, photographs, magazines, and other materials related to strength training and physical culture. Todd had realized when writing his dissertation in the 1960s that many academic libraries had little information about strength training, bodybuilding, and weightlifting, and so he and Jan, began collecting such materials with the dream of one day establishing an academic library for the strength sports. The Todds realized that dream in 2009, when they moved what had grown to more than 3000 boxes and many pieces of art, into the now internationally famous H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports located in the North End Zone of the U.T. football stadium. Now used by scholars from around the world, the Stark Center has changed our understanding of what belongs within the field of "sport history". The Center is a repository for the large collections of physical culture and sport materials donated by the Todds, by UT Athletics, and by many other donors. It is also recognized as an Olympic Study Center by the International Olympic Committee. The Stark Center was yet another of Terry Todd's visionary ideas and he has been the Center's primary fundraiser. Todd was actively working toward an endowment goal of $10M needed to ensure the Center's future when he passed.

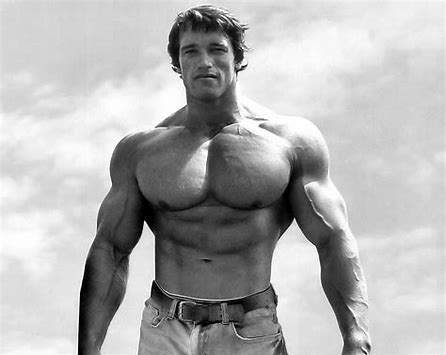

In 2001, Todd was asked by Arnold Schwarzenegger and his partner, Jim Lorimer, to create a Strongman contest for the Arnold Sports Festival, held annually in Columbus, Ohio. Now recognized as the most prestigious contest in the Strongman sport, the Arnold Strongman Classic Todd created has transformed the sport itself. Todd prided himself on offering the highest prize money in the sport and in creating events for Arnold that measure true strength and not endurance.

Creating and running the Arnold Strongman Classic not only kept Todd at the forefront of the Iron Game but also led to new opportunities for Todd to unite history and strength in a series of documentary films for which he served as producer. Sponsored by barbell and equipment manufacturer Rogue Fitness, of Columbus Ohio, the documentaries are available free on Rogue's Facebook page and include Levantadores, about Basque rural sports and stone lifting in Northern Spain; Stoneland, exploring the strength traditions of Scotland; a new 90-minute film on Iceland's strength traditions that will premiere this summer, and biographies of strongman Eugen Sandow and Louis Uni.

Todd's is an unmatched legacy in the history of the Iron Game. He was inducted into the International Sports Hall of Fame in 2018; received the National Strength and Conditioning Association's highest honor—the Al Roy Award—in 2017; was honored as a "Legend" by the Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association in 2009, has been inducted into both the men's and women's powerlifting halls of fame, and, in 2013, received the Honor Award of the North American Society for Sport History for his contributions to that academic field. As a long-time friend said when they learned of his passing on Saturday, "It may seem that our world is a bit weaker today but actually we are all immeasurably and eternally stronger for having known him."

Jul. 14, 2017

In 2017 Terry Todd was honored with the Alvin Roy Award for Career Achievement by the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). This award recognizes those who have contributed significant research and understanding to the field of sports conditioning in training over an individual’s career.

Todd was the director and is the founder, along with Jan Todd, of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center – the world’s most extensive collection of materials relating to sport and physical culture. The Stark Center serves as a library and research center, supporting research on health and performance, and the significance sports contribute to culture and society.

Terry Todd had many career achievements as a professor at several universities, lecturing on subjects relating to drugs in sports, conditioning, and sport/fitness history. Terry Todd was a faculty member for the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education for many years, He also contributed to the study of fitness and training through several books and articles in popular and academic publications on the subject.

How Two Powerlifters Founded One of UT’s Most Unique Places

The AlcaldeFollow

Nov 1 · 13 min read

By Andrew Roush

The Stark Center, UT’s museum and research center dedicated to the study of physical culture, turns 10.

Photos and videos by Andrew Roussh were added by billy dale

Hercules stands watch over the north end of Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium. His head dipped, eyes weary, body in the swivel-hipped pose of European classical sculpture. The great demigod of Greco-Roman myth leans heavily on his club, which is topped by the densely furred pelt of the Nemean lion. This towering figure, easily twice life size, brims with purposefully sculpted muscles, the kind you can only get through focused effort — or, perhaps, through the divine power of a father like Zeus.

The archetypical hero stands imposingly in the lobby of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports, one of UT’s newest and most fascinating public and academic collections.

The Stark Center is a rare institution. It’s a museum and academic research collection dedicated to the study of physical culture. Initiated in Germany in the 19th century, the health and wellness movement grew in popularity in the U.S. over the century due to increased immigration from Germany, a reaction to the more sedentary lives of the growing white-collar class, and an evolving belief in the value of personal health and wellness, among other factors.

It is also a place unafraid of the “culture” in physical culture. The Stark Center, envisioned and created by husband-and-wife powerlifters and UT professors Terry and Jan Todd, holds a trove of rare photos, books, documents, memorabilia, art, and more on the subjects of strength training, weightlifting, strongman contests, and other historical feats of strength. Among the collection are more than 30,000 books and a full array of recorded media, from correspondence, posters, and promotional materials to films and, of course, statuary. It includes the collections of Tom Kite, BBA ’03, Life Member, and Ben Crenshaw, ’73, Life Member, along with vast holdings related to the early years of athletics at UT. Opened in 2009, the Center also has a strong focus on the most classical of sporting contests, the Olympics. To that end, it contains one of the two Olympic Study Centers in the United States, denoted by the International Olympic Committee in 2011.

Few universities could balance the counterweights of old-fashioned sport, the kind of vim-and-vigor, health-centric views of physical culture, with modern notions of physical excellence and of intellectual and academic virtue. Think leotard-and-handlebar-mustache strongman meets tweed-with-elbow-patches man of letters. Though only a decade old, the story of the Center stretches back to the beginning of athletics at Texas. It took root here because UT is the kind of place that can attract two record-holding powerlifters with a bold vision — the kind of place that can draw people like Terry and Jan Todd.

The 10 feet, 6 inches tall, 2,000-pound plaster cast of the Farnese Hercules statue in the Stark Center lobby, sculptor unknown.

When Terry Todd died at age 80 in July 2018, his obituary struggled to hold all that he was. He was described as a “writer, academic, journalist, champion lifter, coach, sport promoter, founder of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports at The University of Texas at Austin, and director of the Arnold [Schwarzenegger] Strongman Classic.” The latter two achievements came later in life, after the Todds came back to Texas. By the time they did, they were the biggest names in powerlifting.

Powerlifting was a brand-new sport in 1964, when Terry, BA ’61, PhD ’66, Life Member, became its first champion. He began his path to becoming a legendary lifter at UT, where he lettered not in weightlifting or football, but in tennis. Before college, he’d already captured titles in table tennis and even in the citywide Cheerio-Top Yo-Yo Competition in Austin, where he grew up.

He had initially started weight training in 1956 with the intention of making his left arm as strong as his right. By the time he was a Longhorn tennis player, his arms and shoulders had grown bulky in comparison to the more lithe figures of tennis players. In photos from the time, Terry looks more like a football player holding a fly swatter than a tennis player ready to hit the court. Todd’s coach, Wilmer Allison, told him to lay off the bodybuilding, fearing Todd would become too hard and steely to execute the flexibility and precision tennis requires. Terry didn’t believe this, and poured himself into the new world of powerlifting, defined by three now-common lifts: the deadlift, the bench press, and the squat. He’d already claimed the national junior Olympic weightlifting contest in 1963, and won the first national powerlifting championship in 1964. He soon became one of the biggest names in the sport, winning the first senior nationals competition in 1965.

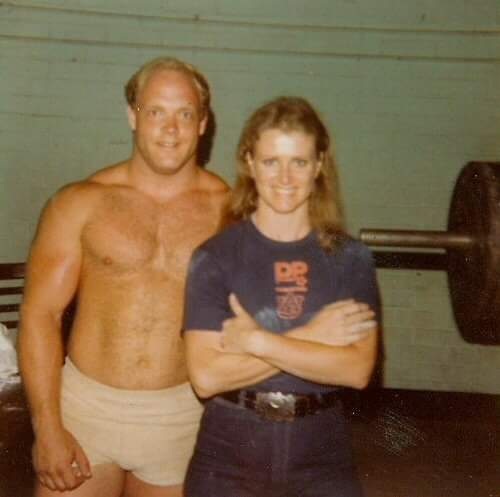

A 1977 article in Sports Illustrated, a publication held in its entirety today at the Stark Center, described the sport of powerlifting as “elemental,” contrasting it to the graceful, swift, and tightly regulated Olympic weightlifting category. “Technique plays a part, but not nearly so much as brute strength,” wrote SI author Sarah Pileggi. Her story chronicled the rise of a new star in women’s powerlifting, one who would go on to win the first women’s championship that same year. In fact, Jan Todd, PhD ’95, Life Member, organized the event with the help of her husband, Terry.

Terry had already retired from the competitive lifting world by the time he met then-student Jan in 1969 at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. He was a professor of education, physical education, and sociology, who, SI noted, was “visible not only because of his size but also for his activist stance on the campus issues of the day.” During his time at Mercer, from 1969–75, Terry, who was white, founded the African-American Studies program and hosted a series of seminars on educational theory and reform.

But the article was about Jan. Titled “The Pleasure of Being the World’s Strongest Woman,” it outlined how Terry and Jan met at Mercer, how she had learned of the great strongwomen of history, the circus performers and vaudeville acts of yore; how the two had fallen in love; and how, after Jan graduated, they married. They eventually moved to Nova Scotia, where Terry took a job as a professor at Dalhousie University, while Jan helped teach strength training to local women and ran a 100-acre farm, managing one-ton bay horses and helping produce 5,000 bales of hay in July of 1977.

“She was never afraid to try anything. I guess I admired that most about her,” Terry told SI. “She was a natural force. Mount Rushmore. She had a sort of love-hate relationship with the college president [at Mercer]. She was a thorn in his side when she was editing the [school news]paper, but once I heard him say, ‘She’s a helluva man.’ That was his greatest compliment.”

Jan’s grandfathers on either side worked with their hands: Suffolk worked for U.S. Steel in Pennsylvania, where her father eventually worked before moving on to other jobs in steel, and Yerty was a carpenter. Born Jan Suffolk, she was always a tomboy, but also ran the household while her mother supported the family as a nurse: doing laundry, cooking, baking, cleaning, and preparing food. In high school, she was named — “to her everlasting embarrassment,” according to SI — the “Betty Crocker Homemaker of Tomorrow.”

At Mercer, Jan took square dancing as her physical education class. “I wasn’t thinking of myself as an athlete then,” she laughs.

But being married to the world’s foremost expert in weightlifting can alter how you see your own athletic prowess. Terry brimmed with knowledge of strongmen (and women) throughout history, and was the rare, if only, scholar in the field. It was a knowledge borne from a sharp memory and a ravenous desire to collect as much material related to strength as possible, especially since few others were doing it. He was the kind of expert whose doctoral dissertation on progressive resistance training came complete with a 300-page, annotated bibliography.

“After we married, I would sort of tag along with him to the gym,” she says, “but I was never interested in the kind of cosmetic work women were encouraged to do at the time.” Then, on a visit to Austin, she met a woman who competed in men’s lifting classes. That changed everything. Hearing Terry describe to her the history of sideshow strongwomen, culled from his encyclopedic knowledge, ignited something in Jan. They believed that, with training, she could clinch a Guinness world record for the highest two-handed lift by a woman. Just a few years later, she did exactly that, raising 394.5 pounds.

Growing up, Jan had few examples of female athletes. But by the late 1970s — with Billie Jean King, with Title IX — the scene was set for change. “I began to realize how important it was for women to try hard, to do these things,” she says.

Together, with much cajoling of male-centered gym owners, Jan and Todd worked to formalize women’s powerlifting, while at the same time continuing to study the history of strength-training. By the time they came to the Forty Acres in the 1980s, they had in tow 385 boxes of sporting memorabilia and research. After another two decades of digging into barns and old homes in search of rare collections, they had amassed more than 3,000 boxes of records and items related to physical culture — all waiting to be revealed to the world.

H.J. Lutcher Stark, whose last name fittingly translates from German as “strong,” was born in 1887 with a sylvan spoon in his mouth, as the only son and scion of a vast fortune made from East Texas timber. He loved sports, and football in particular, eventually enrolling in UT and becoming manager of the football team before graduating. His first donation to his alma mater was a set of blankets for the team, emblazoned with a nickname that would soon become official: Longhorns.

That same year, 1913, Stark, BA 1910, decided to take up weight training with a Philadelphia-based expert named Alan Calvert. The era was still defined by the belief that over-building muscle would leave one musclebound, too tight from musculature to be truly physically fit. But Stark returned to Texas with 40 of his 200 pounds melted from his 5-foot-7-inch frame and a mind full of the potential of weight training, a notion now practiced by strength coaches in locker rooms around the world.

Stark, somewhat nebbish-looking in pince-nez spectacles but square-headed, was friends with L. Theo Bellmont, then-secretary of the Houston YMCA. They bonded over their love of lifting iron, and Stark convinced the UT Board of Regents, which he would later serve on for 24 years, replacing his father, William Henry Stark, to hire Bellmont as the university’s first athletics director. In turn, Bellmont hired Roy McLean, a wrestler and weightlifter, as his secretary. Eventually, “Mac” was taken on as a coach, and at UT, he taught the first organized, university-level heavy weight-training classes ever taught in the U.S. By the 1950s McLean had taken a shine to Terry, then a master’s student, sharing with him what would become the Todd-McLean Collection, the basis of the modern Stark Center collection. Today, the Todd-McLean Library holds rare pamphlets, letters, and photos, including the remarkable archive of Ottley Coulter, a circus performer and strongman whose family, over the years of box-gathering, became close with the Todds.

Together, Bellmont, Stark, McLean, and finally the Todds set the standard for athletic achievement, and the theories of sport and education that went with it, for future generations of Longhorns. With a repository of rare knowledge, they set about the herculean task of giving it all a place to live and grow. That legacy would reach its zenith when the Stark Center moved its collections from the Anna Hiss Gymnasium (previously, the collection was housed in Gregory Gym, before a renovation in the mid 1990s) and found its permanent home — appropriately alongside Bellmont Hall — in DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium in 2009.

Following Texas football’s national title, in 2006, the university was making an investment in expanding the stadium, and then-Athletic Director DeLoss Dodds and UT administration agreed that the 800,000 square-foot addition to the north end zone area seemed just the fit for the already well-regarded Todd-McLean Collection. Now Terry and Jan had to raise $3.5 million to help make the proposed 27,500-square-foot facility a reality. Donors like bodybuilding empresarios Joe and Betty Weider helped the Center get its footing. The Todds also got major support from the Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark Foundation, started by the bespectacled regent who helped hire Bellmont, and who lifted weights with both Texas’ first athletics director and McLean.

From left: Magazine covers, including the February 1957 issue of “Muscle Builder,” featuring Betty Weider, who appeared on more than 300 covers; original strongman and strongwoman show posters, including Katie Sandwina and French strongman Apollon (center).

The 1977 SI article brought the Todds a measure of fame outside the small world of their new sport. In 1978, Jan went on the Tonight Show, ostensibly to teach Johnny Carson how to deadlift a barbell loaded with 415 pounds. She instructs him in the technique, Johnny lowers himself, grabs the bar, and pulls. He cannot move an inch, and begins immediately howling with laughter at the difficulty, the seeming impossibility. Eventually, he invites the evening’s other guests, Carl Reiner and Jack Klugman, over from the couch. Together, they are able to lift the weight, which Jan managed on her own in one try.

Terry and Jan moved to Terry’s hometown in 1983. They both joined the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education in the College of Education, eventually taking up and operating a 300-acre Central Texas cattle ranch complete with a menagerie of livestock, including five peacocks, a Percheron draft horse, 50 head of cattle, two Sicilian donkeys, three English Mastiff dogs, an emu, and three Maine Coon cats. By then, Terry had been building on McLean’s collection of manuscripts and ephemera, written his own books and articles, and edited sports magazines. In 1979, he helped establish the National Strength Research Center at Auburn University, and in 1990 created Iron Game History: The Journal of Physical Culture, an academic journal. Despite this, the Todds were well aware of the dearth of academic resources on the subject of strength-based sports, and continued the quest to gather as many handbills, posters, photos, and various collectibles as they could find, then work to give them a place that would preserve and share them.

“We had many collecting adventures,” Jan says, but eventually, things were ballooning to near-unmanageable size. “It was sort of like buying the albatross to hang around your neck.” They realized the best solution was to create a permanent research center for the subject.

“I still say ‘we’ all the time,” Jan says about Terry and the Center’s work. “We’re so proud of it, and the people who helped.”

The Stark Center’s Teresa Lozano Long Art Gallery, featuring original works of art and two sculptures on loan from the Blanton Museum of Art.

Barbells, dumbbells, and other pieces of strength training equipment in storage.

The Farnese Hercules reproduction that rests in the Stark Center lobby is a fitting mascot. Like the stony giant who stands watch at its door, the revelation of the Stark Center to the world was the kind of unexpected achievement that comes from lifetimes of immense effort. Call it a heavy lift, a series of events and of people who came together to protect a rare cache of human culture.

Inside, striking photos abound of many eras of bodybuilders and strongmen, from Ottley Coulter to Lou Ferrigno and, of course, Arnold. In the lobby, the tired Hercules is almost done with his labors, clutching the apples he took from the nymphs known as the Hesperides, the 11th of his 12 labors. In one version of the tale, Hercules convinces Atlas, the Titan who holds the world literally on his shoulders, to go into the orchard and take the apples while Hercules holds up the world for him. When Atlas returns, he tries to leave his post, offering to take the apples back himself. But Hercules, both cunning and strong, asks Atlas to take up the world again, just for a moment, so Hercules can adjust his cloak. When Atlas is burdened once more, the hero escapes with his reward.

It’s highly fitting then that this vision of Hercules, the strong man, has just returned from a heroic work combining the strength of mind and body, cunning and power. The door he guards is one behind which both kinds of strength are, together, valued. Reflecting on it all, Jan notes that the process of piecing together the Center was not unlike the labors of Hercules — at least his famous fifth labor.

“There were very many times,” she says, “when it felt like I was cleaning out the stables.”

Photographs by Nick Cabrera

A previous version of this article stated that H.J. Lutcher Stark’s father was named Lutcher Stark. His name was William Henry Stark.

A misreading of a joke from Terry Todd in the Sports Illustrated article about Jan’s grandfathers being circus geeks has been corrected. One worked in steel and the other as a carpenter.

The Stark Center did move from Gregory Gym to DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium, but first briefly moved to Anna Hiss Gym. The Alcalde regrets the errors.