Spanky Stephens who put together the team who wrote Natasha’s Law says “many do not realize that if a student continues to play with a concussion and receives a second head injury, there is a greater chance of severe brain damage or even death. “

Concussions in high school athletes may be a risk factor for suicide - UTHealth News - UTHealth. November 2019 - click on the link below.

https://www.uth.edu/news/story.htm?id=96956fae-b3fc-4d8b-a501-b6da7f10a7e9

Spanky Stephens a former Longhorn has taken the lead in concussion guidelines in sports

“Natasha’s Law is just the beginning,” Stephens said, “and it has stimulated the need for more research."

Deuell, who is also a physician, said coaches, parents, and student-athletes could misunderstand the symptoms and impact of concussions. “We want to create guidelines for the people responsible for protecting the children — parents, coaches, trainers,” he said. “A lot of them have questions.”

The Texas Governor has signed the concussion legislation into law; it is called Natasha’s Law, named after Natasha Helmick, a powerful advocate for this legislation.

We happened upon this legislative piece when we were examining the Illinois process and felt it was very good and forward-thinking. The highlights again include;

Concussion Management Team

Removal from Play

Waiver and Graded Protocol to Return to Play

Specific Education/Training for all HCP’s

State Wide Tracking/Logging of Concussions

Texas is now the 21st state with enacted legislation.

FUMBLE IN THE NCAA

A new brain injury lawsuit could be the undoing of college football as we know it

By Katherine Ellen Foley & Ephrat Livni June 11, 2018

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) dropped the ball when it came to protecting football players’ brains, argues the widow of a deceased player in a lawsuit about the neurodegenerative disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

Just a year after the National Football League (NFL) settled for $1 billion with the families of players who suffered brain damage, and after the college athletes’ league reached a settlement to provide free biannual medical screening for athletes, the NCAA will tackle the matter again publicly in a Texas civil court. But this time, the NCAA officials will have to testify in front of a jury. The trial, which begins today (June 11), will be the first time NCAA representatives will have to answer questions in court about brain injury, revealing just what they knew about CTE and the risks of playing football, how long they knew it, and whether they hid information about those dangers from college athletes.

The plaintiff in this case, Debra Hardin-Ploetz, is the widow of Greg Ploetz, a linebacker and defensive tackle for the University of Texas from 1968 to 1972. He never played professionally, but in 2015, after he died, neurologists from Boston University who examined his brain concluded that he had the most severe form of CTE, and that the disease is what killed him.

Although Ploetz stopped playing football after college, he experienced symptoms of CTE, including depression, aggression, and confusion shortly after graduation. Eventually, he lost the ability to communicate in full sentences, responding only “yes” and “no” to questions and requiring full-time care.

In 2017, Hardin-Ploetz sued the NCAA for over $1 million on two grounds, reports Sports Illustrated: First, for negligence generally, meaning that the NCAA did little to warn or protect players like Ploetz about CTE, while knowing the dangers of playing the sport and taking years of hits to the head. Second, for wrongful death, which is a negligence claim made by the victim of someone who is deceased and applies to Ploetz specifically.

The NCAA, for its part, argues that because Ploetz knew the dangers of playing a contact sport, it isn’t liable for his death.

At the time Ploetz played in the NCAA, the league had no public policies on managing head injuries and concussions, and no rules about what colleges had to tell players, according to a deposition (pdf) of Mary Elizabeth Wilfert, associate director of the NCAA Sport Science Institute.

Today, universities must have comprehensive plans to care for athletes who become concussed, including criteria for when players are allowed to return to practice, games, and the classroom. Each player must sign a waiver acknowledging that they understand that their particular sport puts them at risk of head injury. Football players must wear (pdf, p. 106) knee pads, shoulder pads, mouthguards, and helmets with a faceguard and chin strap that meet impact testing standards set by the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment. These helmets, too, must contain a warning label about the risks of obtaining head injuries.

Hardin-Ploetz’s attorneys have noted that it took the NCAA 12 years from the time they learned that mouthguards could help prevent concussions and other injuries to implement rules requiring the equipment. And that’s even when the recommendation to enforce mouthguard use had come from one of the NCAA’s own safety subcommittees. The attorneys say is this evidence the association wasn’t overly concerned with player safety.

The widow’s claims in this case are somewhat analogous to Big Tobacco cases. For decades, Big Tobacco hushed the scientific research showing that smoking does in fact cause lung cancer. Smokers may have suspected that their habit was dangerous, but companies were still found liable in the courts for failing to publicize science on the actual dangers. Similarly, the NFL for a long timed denied the link between playing football and developing CTE later in life, despite the fact that neuroscientists have known for many years that repeated hits to the head, and not just concussions alone, directly cause the neurodegenerative disease. Players may understand a contact sport is risky, but if an athletic association or league failed to disclose known risks and failed to take precautions that could have prevented harm, it can, arguably, still be held liable for negligence and CTE deaths, no matter what players knew.

The NCAA has tried to block Hardin-Ploetz at every turn in this case, fighting her lawyers’ requests to depose association doctors and generally trying to minimize discovery. The deposition testimony shows acrimonious and contentious exchanges, with NCAA attorneys objecting to many questions, and the widow’s legal team complaining they can’t get the answers or witnesses they need.

While the trial isn’t likely to be a friendly affair, all parties will have to play a more civil game. If the NCAA seems to be blocking questions or otherwise indifferent to the plight of players, jurors will probably not be happy with the association.

On the other hand, a jury of Texans—who famously love college football— might be wary of what Hardin-Ploetz’s claims could do to the beloved pastime. If she wins, more former players may bring their CTE cases to court—which may result in further testimony from the NCAA on the dangers of football-playing, and could eventually influence the way football is played at the collegiate level. This, in turn, could put pressure on the NFL to do the same.

Although it’s hard to speculate, one such change would be transforming the way players are allowed to tackle one another. According to an analysis of the 2015 to 2016 season, tackling was the number one cause of concussions during games, and most of them come from helmeted head slamming into bodies. Theoretically, barring cross-body tackling—where a defensive player runs at an offensive player sideways with his head and chest across the offensive players body—and a win for the widow of a CTE victim in court would certainly help that cause..

However, college and professional football are high-stakes sports. If spending time learning alternative tackles takes away a team’s competitive edge, it may ignore new rules or find work-arounds to allow its players to continue making the sports’ characteristic big hits.

Football has already dropped in popularity in recent years, and a win for the widow in this case isn’t likely to help. Some fans may resist any resulting changes to beloved football traditions, while others may see the case as one more reason to abandon the sport.

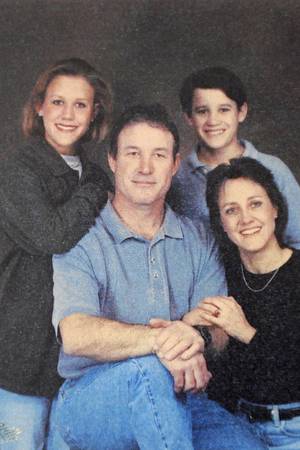

The San Antonio Express-News article by Mike Finger June 2, 2018 Pictures to Mike's article were added by Billy Dale . Greg was my teammate and Julius was my roommate.

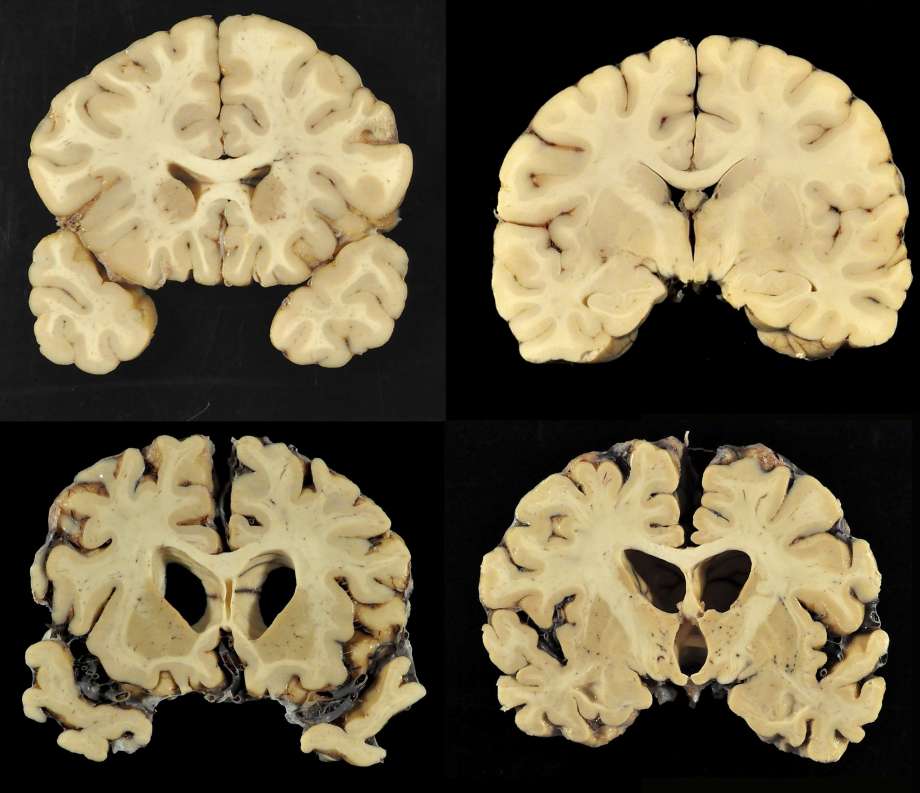

This combination of photos provided by Boston University shows sections from a normal brain, top, and from the brain of former University of Texas football player Greg Ploetz, bottom, in stage IV of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. According to a report released on Tuesday, July 25, 2017, by the Journal of the American Medical Association, research on 202 former football players found evidence of a brain disease linked to repeated head blows in nearly all of them, from athletes in the National Football League, college and even high school. (Dr. Ann McKee/BU via AP) less

Mildred Whittier still has not made it to the inside of a courtroom. It has been four years since she filed a lawsuit against the NCAA on behalf of her trailblazing brother, who battles dementia almost five decades after he became the first black football letterman in Texas Longhorns history.

Still, she waits.

Zack Langston’s family is waiting, too. In 2014, the former Pittsburg State linebacker committed suicide at 26, leaving behind instructions to have his brain studied for evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. Now, his case against the NCAA has been folded into a class-action lawsuit potentially involving thousands of former players.

For all of those families, a resolution could be years away.

But a week from Monday, Debra Hardin-Ploetz will not have to wait anymore. On June 11, she is scheduled to appear in a Dallas courtroom, where her attorneys will argue that the NCAA is legally responsible for her husband’s death.

It will be the first time a CTE case ever has gone to trial in this country. And for the NCAA, it will mark the beginning of what could be a momentous stretch of legal tumult that could leave a lasting effect on the governing body whose original stated mission is “to keep college athletes safe.”

Later this year, the NCAA will have to defend its limits on compensation for student-athletes in a trial set for a California courtroom. That case, legal experts say, has the potential to upend the entire concept of amateurism in college sports.

But in many ways, the CTE trial in Dallas could wind up being just as significant. That case revolves around Greg Ploetz, who played football at UT in 1968, 1969 and 1971, and died in 2015.

According to a clinical report cited in his wife’s lawsuit, Ploetz suffered a myriad of serious health problems throughout his life, and “became apathetic, disinhibited, exhibited compulsive behaviors, and his personal hygiene began to decline. He experienced paranoia and confusion, was psychiatrically hospitalized, and was in and out of respite homes due to aggressive behaviors.”

Neurologists at Boston University, who studied Ploetz’s brain after his death, concluded he suffered from stage IV CTE, the most severe version of the disease. Those same researchers recently published a study stating CTE was found in 99 percent of brains obtained from NFL players, 91 percent of college football players, and 21 percent of high school football players.

With that link in mind, the most important question to be settled in the Ploetz trial is this:

To what extent should the NCAA be held responsible for protecting athletes?

When the jury provides its answer, the effect could be huge. In an interview with The Brookings Institution, Donna Lopiano, the former UT women’s athletic director and former CEO of the Women’s Sports Foundation, estimated that the NCAA could face “at least a billion dollars in concussion liability.”

To win her case, Hardin-Ploetz — who is represented by Houston attorney Eugene Egdorf — will need to prove the NCAA was negligent.

Michael McCann, a legal analyst for Sports Illustrated, broke down the keys to proving that argument like this:

“Hardin-Ploetz insists that 1. the NCAA openly acknowledged a legal duty to minimize the risk of injury to Ploetz while he played college football; 2. Ploetz relied on the NCAA to satisfy this duty, and 3. the NCAA failed to meet the duty.”

The NCAA, of course, is likely to argue that college football players assume the risk of injury by voluntarily playing a physical sport and that the governing body had no duty to protect players as extensively as the Ploetz lawsuit suggests.

But Egdorf will have plenty of evidence to suggest otherwise. According to Sports Illustrated, Hardin-Ploetz’s lawsuit cites a 1933 NCAA medical handbook recommending that concussed players be held out for 48 hours, which could suggest that the NCAA should have required safety measures even during Ploetz’s career.

The plaintiff also could bring up NCAA president Mark Emmert’s 2014 testimony before the U.S. Senate, when he said, “I will unequivocally state we have a clear moral obligation to make sure we do everything we can to protect and support student-athletes.”

Hundreds of families, from the Whittiers to the Langstons to all of those filling the class-action suits still pending, believe the NCAA did not meet that obligation. Many of them have been waiting a long time to make that argument.

In just a few days, they finally will get to hear someone make it for them.

mfinger@express-news.net<mailto:mfinger@express-news.net Twitter: @mikefinger

INFORMATIONAL ONLY- The comments below are not endorsements by tlsn

NOTICE OF AMENDED TIMELINE IN THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT OF CLASS ACTION AND FAIRNESS HEARING FOR MEDICAL MONITORING AND RELEASE OF CLAIMS MAY 23RD 2017

On May 23, 2017, the Court issued a Scheduling Order which amended the timeline in the class action lawsuit called In re National Collegiate Athletic Association Student-Athlete Concussion Injury Litigation, Case No. 1:13-cv-09116 (N.D. Ill.). It is pending in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois.

This Scheduling Order can be viewed at the Settlement Website, www.collegeathleteconcussionsettlement.com, and extends the deadline to request exclusion from or object to the Settlement to August 4, 2017, and rescheduled the Fairness Hearing for September 22, 2017, at 10 a.m. at the Everett M. Dirksen United States Courthouse for the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, 219 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, Illinois.

In re: NCAA Student-Athlete Concussion Injury Litigation, c/o Gilardi & Co. LLC, PO Box 43414, Providence, RI 02940-3414

5/22/2017

Saw this last week about a young lady with a remarkable recovery. This is the same group that Bob Lilly and others have treated with.

From Deb Ploetz

Greg Ploetz and many more of our teammates have paid the ultimate price from football-related concussions. The organization below is seeking funding to continue research on how to lessen the impact of this contact injury on players who have CTE.

http://concussionfoundation.org/story/greg-ploetz

Article Written by Terry Frei for the Denver Post about CTE and Greg Ploetz death

Many..... still are shaken by the September 2013 death of, the charismatic Wishbone wizard and the father of former Rockies pitcher Huston Street. Street died of a heart attack. Also, James Saxton, the Texas running back who finished third in the 1961 Heisman Trophy voting (behind Syracuse’s Ernie Davis and Ohio State’s Bob Ferguson), passed away at age 74 last week after a long battle with dementia. At least one other prominent player in the Texas program from 1969-72 also is fighting dementia.

In communicating with Dale during this process, and telling him how much I respected how the LSG has responded to help Ploetz and other former Longhorns and their families, I mentioned that my father was the head coach at Oregon during that period, and I’ve been reminded again and again over the years about how the bonds between teammates — and between coaches and players — last. The latest was when three of my siblings and I were present as our father posthumously was honored at the Oregon spring game on May 3, tying it the military appreciation theme of the afternoon because he had been a decorated P-38 fighter pilot during World War II … and never allowed that to be included in his coaching biography. (He was an Army Air Forces contemporary of Ploetz’s father, Frederick Ploetz, the P-40 fighter pilot, also in the Pacific Theater.)

I feel comfortable with sharing what Dale wrote me about the teammates’ bonds issue:

“Bonding only occurs when the respect of a teammate is earned. We all respect each other. We struggled through the mental anguish of trying to be a starter for the Longhorns. We shared victories, losses, work-outs, fellowship, sorrow, pain, and joy together and now that most of us are entering the 4th quarter of our lives, we huddle again as a team to help each other. The teammate bond is not broken and the respect for each other remains years after our glory days at UT have ended.”

Greg Ploetz, Former Texas Football Player, Dies At Age 66

Questions are now being raised about the association of CTE to football head trauma. There are now scientific arguments that question CTE as the primary cause for head injury. Please see link below.

Article in Dallas Morning News- Kevin Sherrington in 2015

Greg Ploetz hasn’t played a football game in more than 40 years, but the scar still shows. An undersized All-Southwest Conference defensive tackle at Texas, he earned it. A “warrior,” one teammate called him. Now, at 65, Ploetz couldn’t so much as handle the crowd noise at the Big Shootout. Conversation confuses him. Walking is sometimes terrifying. In his tortured mind these days, a crack in the floor looms like a leap across a deep, dark crevasse.

Ploetz — pronounced Plets — suffers from what neurologists call “mixed dementia,” the probable result of head trauma from his days as a 5-11, 205-pound lineman at Sherman High and Texas. Doctors can’t tell his wife, Deb, if he’s a victim of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, the progressive degenerative brain disease linked with multiple concussions, harrowing news reports and a lawsuit against the NFL.

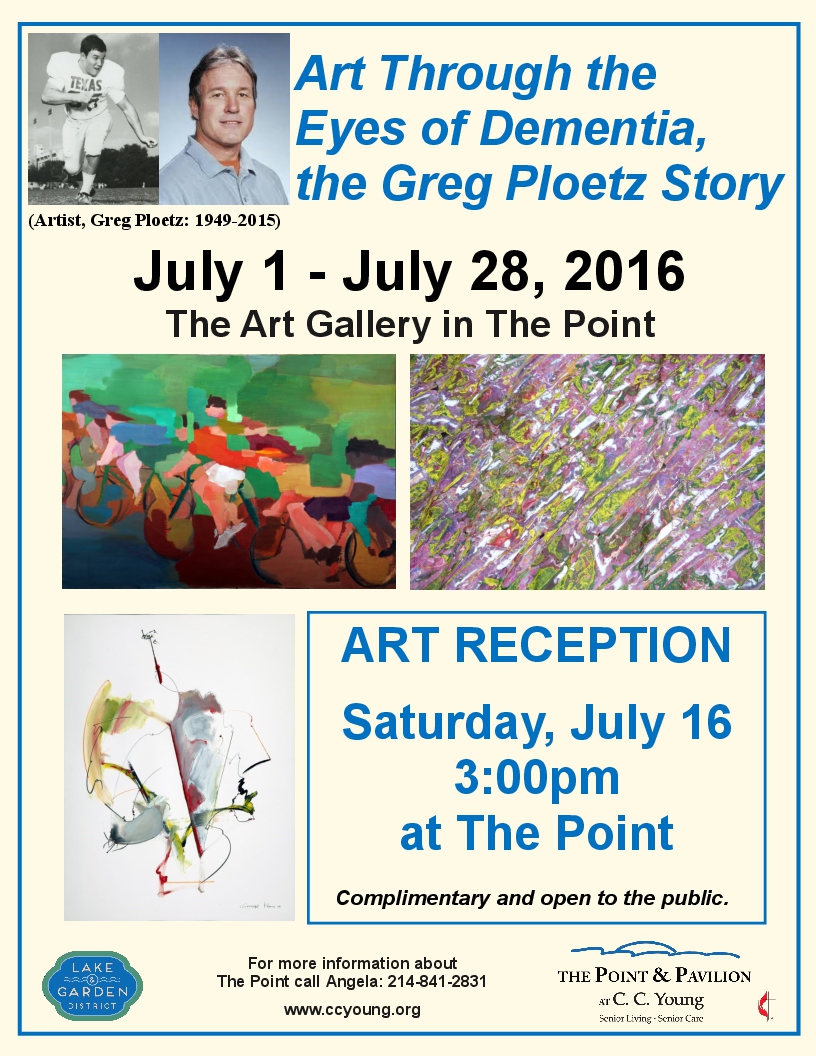

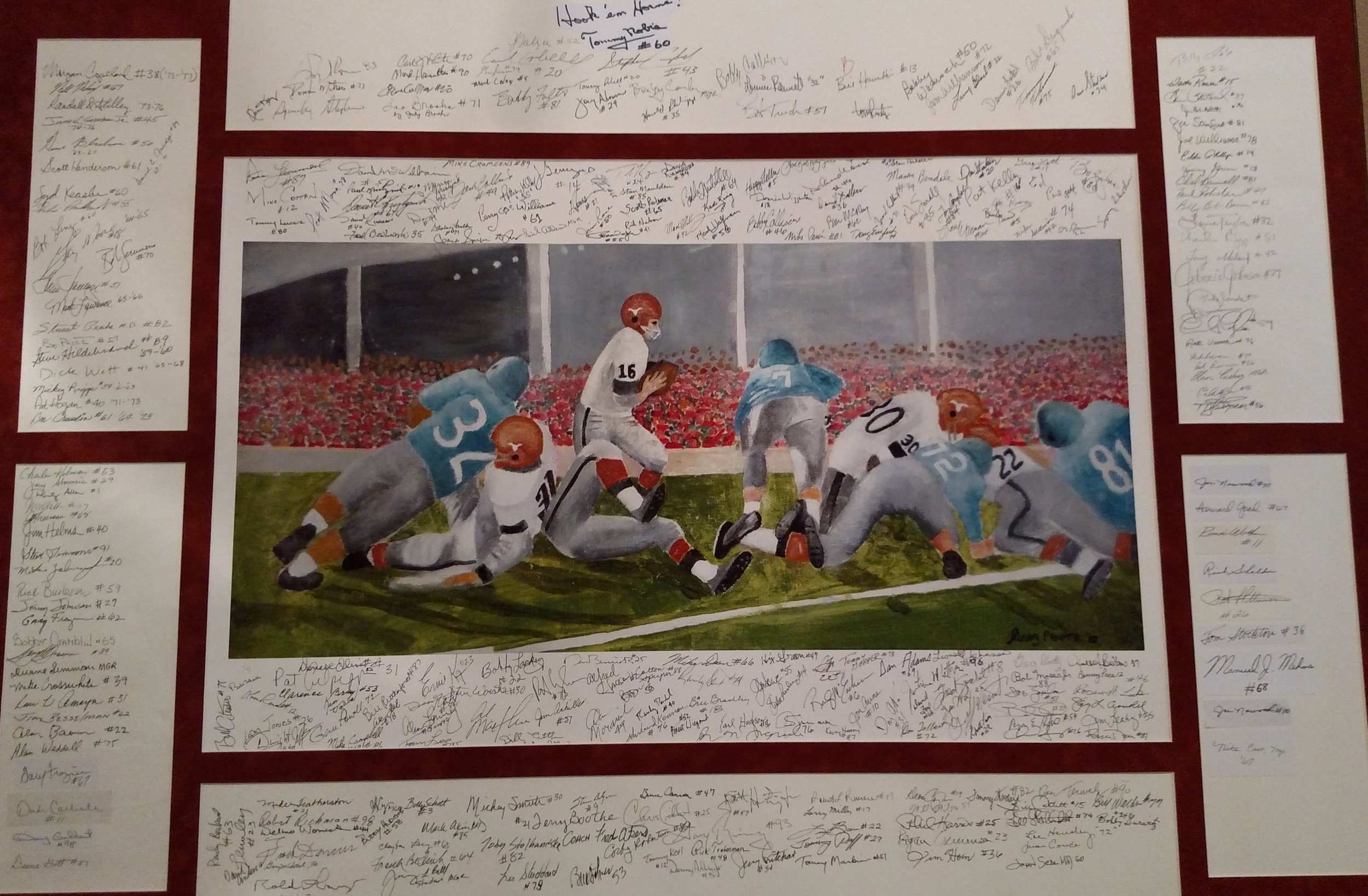

One of Greg’s last paintings while struggling with CTE signed by 285 DKR players

They won’t know for sure until after he’s dead. A year, maybe two.

If there’s any difference between Ploetz and the more than 4,000 plaintiffs in the NFL suit, it’s that he never played pro football. His last game was the ’72 Cotton Bowl, against Penn State.

Other than occasional financial assistance from former Texas teammates, no help is coming to the Ploetzes, as it may yet for the NFL plaintiffs. Texas isn’t liable. Neither is the NCAA. No union push by Northwestern can help them at this point, either.

At least 60 former college players with similar stories have filed lawsuits against the NCAA without success. Even if they’d cashed in, Deb wouldn’t have been a party to it.

“Greg chose to play football,” she says, “so I don’t really hold people liable for the choice he made.”

Talk to players of Ploetz’s generation, and this is the answer you get: I’d do it all over again.

Ploetz was no different until he realized just how different he is.

“Five years ago, he never wanted to recognize that football did this to him,” Deb says.

“The last two years, he stopped watching.”

Now he waits.

Ploetz is too young to die like this, for something he did in his youth, for the honor he brought his school, his family, his memory. He didn’t understand the risk. No one of his generation did. If he played today, he’d have the benefit of concussion protocols and better health care. He could make an informed decision.

He might even be able to put it into words.

What do you do then with men like Greg Ploetz? Write it off as bad luck? Dismiss it as the Ploetzes’ problem? Call it a cautionary tale and leave it at that? Easy enough to do with these men, I suppose, until you hear one of their stories.

Ploetz chose football, not this: An artist, teacher, and gentle soul kicked out of two memory care facilities and an adult daycare center because of aggressive behavior. Darrell Royal once said he could depend on the size of Ploetz’s fight. Whatever else has been stripped from him, the fight remains.

The worst part is, before language and reason left him, he could see it coming.

“Deb, please help me,” he begged his wife. “I don’t want to live like this.”

Mike Dean has been inducted into the Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame and Longhorn Hall of Honor, but when Texas’ coaches came to Sherman his senior year, they were looking for Greg Ploetz.

Only 5-11 and 195 pounds in high school, thick in the neck and chest, son of a World War II fighter pilot, Ploetz was a “warrior,” Dean says. That mentality enabled him to start between Bill Atessis and Leo Brooks in Texas’ 1969 defensive line despite a hairline fracture in one ankle and the build of a short, squat safety.

"It’s a good feeling to have 257 pounds on one side of you,” Ploetz told The Dallas Morning News in the fall of ’69, “and 244 on the other.”

Ploetz more than held his own, particularly against the run. “He was a tackling machine,” says Dean, who started at offensive guard. “He’d run right through people.”

He was a classic ’60s paradox. A high school classmate, Dan Witt, called him quiet, wry, drawn to “artistic, iconoclastic, radical people and elements.” Julius Whittier, who in 1970 became the first black scholarship player at Texas, counted him among a handful of friends on the football team. Everyone liked Ploetz.

Probably didn’t hurt that he played so well. Ploetz was especially effective in the Big Shootout, recording six tackles in the win over Arkansas. It was nearly his last hurrah.

He sat out the ’70 season because he was academically ineligible, a byproduct of his girlfriend getting pregnant and the baby coming early.

“They didn’t know if he was going to make it,” Ploetz told Terry Frei in Horns, Hogs and Nixon Coming, “so I called Fred Bomar.”

Father Bomar baptized Chris Ploetz in the hospital. He was accompanied by Freddie Steinmark. The little Texas safety had already lost a leg to cancer and would die in 1971. Frei wrote that Ploetz couldn’t talk about his son, who survived the ordeal; the baptism; or Steinmark, Chris’ godfather, without choking up.

The summer of ’71, Ploetz was back in Austin, working his way through school, when Texas coaches recruited him again. He asked to sleep on it. That fall, he was All-SWC.

Other than the ankle injury, nothing on Ploetz’s chart hints at any problems to come. Deb says that, in high school, he once wandered to the wrong sideline. Teammates steered him to the huddle and his place in the line.

Greg Ploetz: More On Former Texas Longhorn Fighting Dementia In Colorado

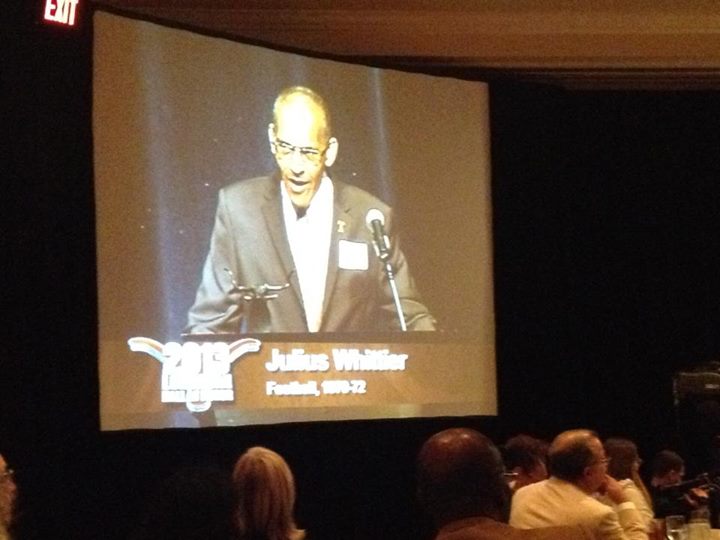

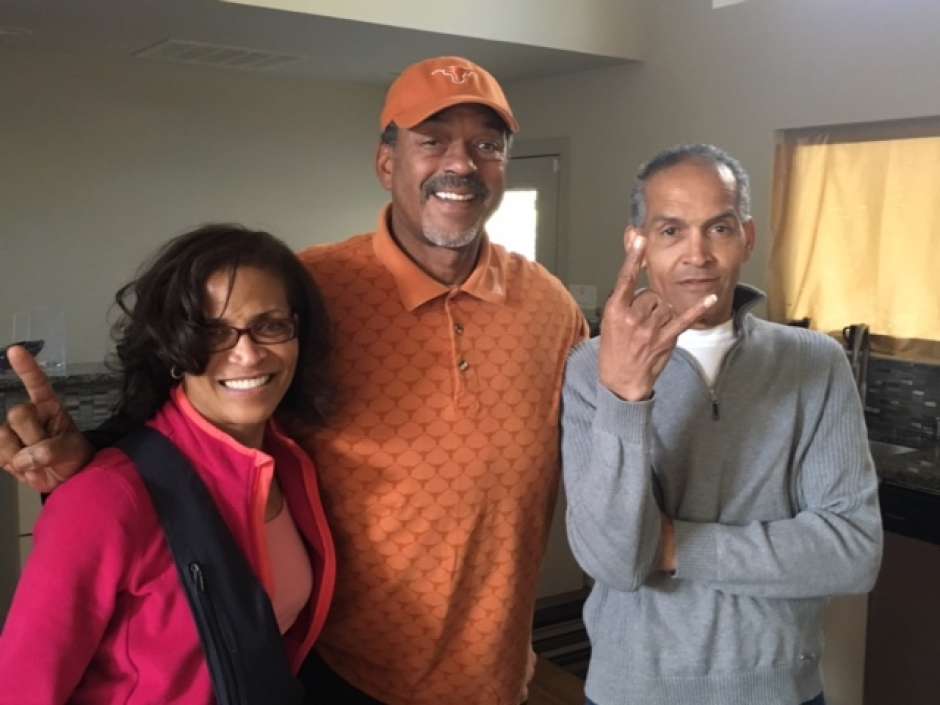

Julius whittier by Millie Whittier

UT ex Julius Whittier battles Alzheimer's as his sister takes on the NCAA

Mike Finger Sep. 16, 2017 Updated: Sep. 16, 2017 8:33 p.m.

Mildred Whittier did not need to know.

Looking back on it, almost five decades later, she can appreciate her youthful naiveté as a gift of kindness from her big brother. She was only a sophomore at Highlands High School when Julius Whittier went off to college in Austin, and she had no idea he was doing anything out of the ordinary.

Julius was going to attend school, and he was going to play football. Simple as that.

Even if he understood everything that went along with integrating the Texas program and becoming the first black letterman in Longhorns history, there was no reason to tell his younger sister.

"I didn't understand the enormity," Mildred said. "The fact that he was the first African-American didn't move me one way or another. I wasn't caught up in him doing anything historic. He was just my brother."

Now, all of these years after he left his mark on the football field and in the courtroom, there is something Julius does not need to know. By not mentioning it, Mildred is returning a gift to him and keeping him unaware of another enormity.

Julius has Alzheimer's disease.

"I never can tell him that," Mildred said. "I don't think he has made the connection, that you have dementia, that you have Alzheimer's. He says he's forgetful. He says, 'I have to rely on my sister.' "

Pushing for change

In a way, others are depending on Mildred, too. In 2014, she filed a class-action lawsuit on Julius' behalf against the NCAA in U.S. District Court. The suit seeks up to $50 million in damages for players from 1960-2014 who did not go on to play in the NFL and who have been diagnosed with a latent brain injury or disease.

That case is separate from a proposed settlement in which the NCAA agreed to set aside $75 million for brain trauma research and testing for current and former athletes. But that settlement offers no financial compensation to injured players, and the goal of Mildred's lawsuit is to establish a fund for the supplemental needs of those suffering from the effects of brain trauma.

The lawsuit claims the NCAA "was fully aware of" and "concealed the dangers of" head impacts in football.

As Mildred watches how the 66-year-old Julius' mind has deteriorated, she remains convinced his days as an offensive lineman and tight end caused it.

"No doubt at all," Mildred said. "He continually spoke of how he was trained to block, using his head. For someone who was as brilliant and as vital as my brother, it's just sad. I've cried so much, I don't think I can cry anymore."

Mildred's cried with former colleagues and teammates of Julius who have stopped by the north Texas memory care facility where he now lives. She can tell he realizes he's supposed to know these old friends, but he doesn't, so he just smiles and laughs.

She has cried with Deb Ploetz, the widow of one of Julius' UT teammates. Two years ago, Greg Ploetz died at the age of 66, and was found to have been suffering from Stage 4 Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Deb, who told the Denver Post her husband would have chosen never to play football "if he knew he would suffer and die like he did," filed a separate lawsuit against the NCAA last January.

"She wanted to stay in touch with Julius and stay in touch with me," Mildred said of Deb. "I think she needed somebody to relate to."

What Mildred and Deb understand is how brain conditions overwhelm not only the patients but also everyone who love them. It begins with a couple of troubling signs, and then a few sleepless nights, and eventually it becomes too much for a man or a woman or a family to bear on its own.

A quick descent

For Mildred, it started in 2012, when the leadership team of Julius' law firm asked her to attend a meeting. He had been in private practice for more than two decades following his stint as a Dallas County assistant district attorney.

He was only 61 at the time, a year away from his long overdue induction into the Longhorns' Hall of Honor. The memories of his days at UT, where as a freshman in 1969 he dealt with the often-difficult circumstances of becoming a racial pioneer and then earned his historic varsity letter in 1970, were still vivid.

But other parts of his mind were slipping, and his fellow attorneys noticed. He would drive to a lunch or a meeting, and wasn't sure where he was supposed to go after that. His bosses told Mildred it might be best if he stepped away from the job.

For a while, Julius continued to live at his home in Oak Cliff, not far from Mildred's work as a systems analyst for the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. She would stop by to eat lunch with him every day, and before long she was attending to some of his hygienic needs, too.

"He started to wander," Mildred said. "He was not able to cook on his own safely, manage himself. I suspected (Alzheimer's) but I didn't want to face up to it. Telling a brother that has been so full of vitality his whole life, it was not easy for me."

Then came a fire at Julius' home, and Mildred used that as a reason to get him to see a doctor. She told him he'd been through a lot of trauma and needed to get "checked up."

He agreed, reluctantly, and Mildred's fears were confirmed. He had early-onset Alzheimer's, and things were only going to get worse.

For a while Julius lived with her in Plano, but in 2016 he moved to the memory care facility. One of his former UT teammates, who has visited the home but asked not to be identified because of the pending lawsuit, confirmed Julius no longer recognizes him.

For the future

Mildred believes this can be prevented. She says one of the main reasons for her suit is because "football is big-time, and we have to do what we can to make sure more people don't suffer through this."

When she filed the suit, Julius knew about it, and was all for it. She says he told her he was glad to be in a position to address the problem, and hopefully to find a solution for those who followed him.

He is not aware of the legal proceedings anymore, though. He does not realize he is suffering from a terrible, cruel disease. Medication keeps him drowsy most of the time, and Mildred says his spirits seldom get lifted.

"I am so happy to say that when he sees me, he lights up," she said. "But then he starts crying. Deep down inside, he understands he might be missing something."

He does not need to know what it is.

Only the rest of us do.