Sports writer Dan Jenkins said about the big shootout. “All week long in Texas the people said Hogs ain't nothing but groceries and that on Saturday in the thundering zoo of Fayetteville, the number one Longhorns would eat ….. hog meat with Worster-Speyrer sauce.

Fifty plus years later, Texas-Arkansas shootout worth remembering

ByLARRY CARLSON Dec 7, 2019

If you don’t really have an interest in UT football games of long, long ago, you probably don’t need or want to get past this first sentence.

And that’s OK.

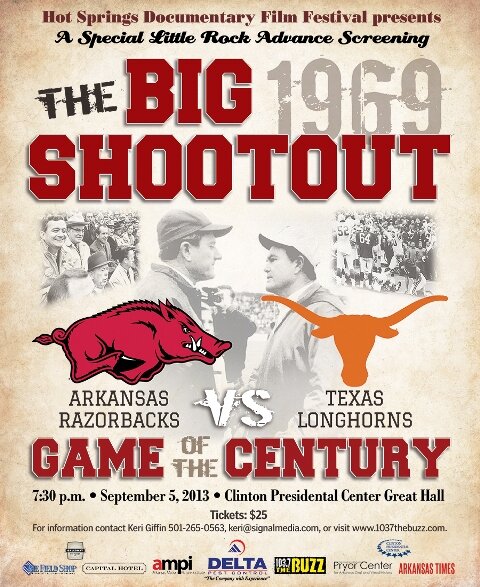

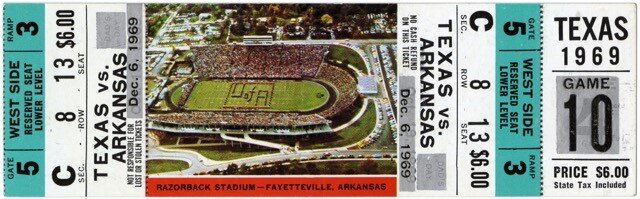

Fifty years is a long time to stare down the barrel of “The Big Shootout,” as the epic Texas-Arkansas game of a half a century ago this month (Dec. 6) came to be billed.

If you’re a Longhorn fan under 60 — and the numbers of us over that age continue, naturally, to shrink — it might not matter so much.

But back then, it meant so much to so many. To some it still does.

I was a high school junior in San Antonio and I’d been getting to attend three home games a year for a decade. The rest were captured by the magic drama of radio and thrice-yearly TV coverage, counting the bowl game that was a Horn fan’s birthright. I knew every player’s jersey number, height, weight and hometown.

And speaking of hometowns, unlike contemporary UT rosters dominated by players from mega-schools in the Greater Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio areas, the ’69 roster was well-represented by stud players from small high schools in sleepy, one-Dairy Queen towns across the Lone Star state.

The great wishbone fullback, Steve Worster, hailed from Bridge City in southeast Texas, just a few miles from the Sabine River and Louisiana.

Ted Koy, halfback and a tri-captain, came to UT with unmatched football heritage and grew up on a family spread outside Bellville.

All-American offensive tackle Bob McKay was from the blink-and-miss-it town of Crane, near the New Mexico border, and home for center Forrest Wiegand was little Edna down on the coastal prairie.

But wherever the players came from, they excelled as a team, beating the hell out of every foe they faced. Texas averaged whipping Southwest Conference foes by an astonishing 42 points per game.

Coming into the Arkansas test, the close call was a ho-hum, 31-0 blanking of Rice.

If you’ve read this far and know your Longhorn lore, you know the classic setting for The Big Shootout.

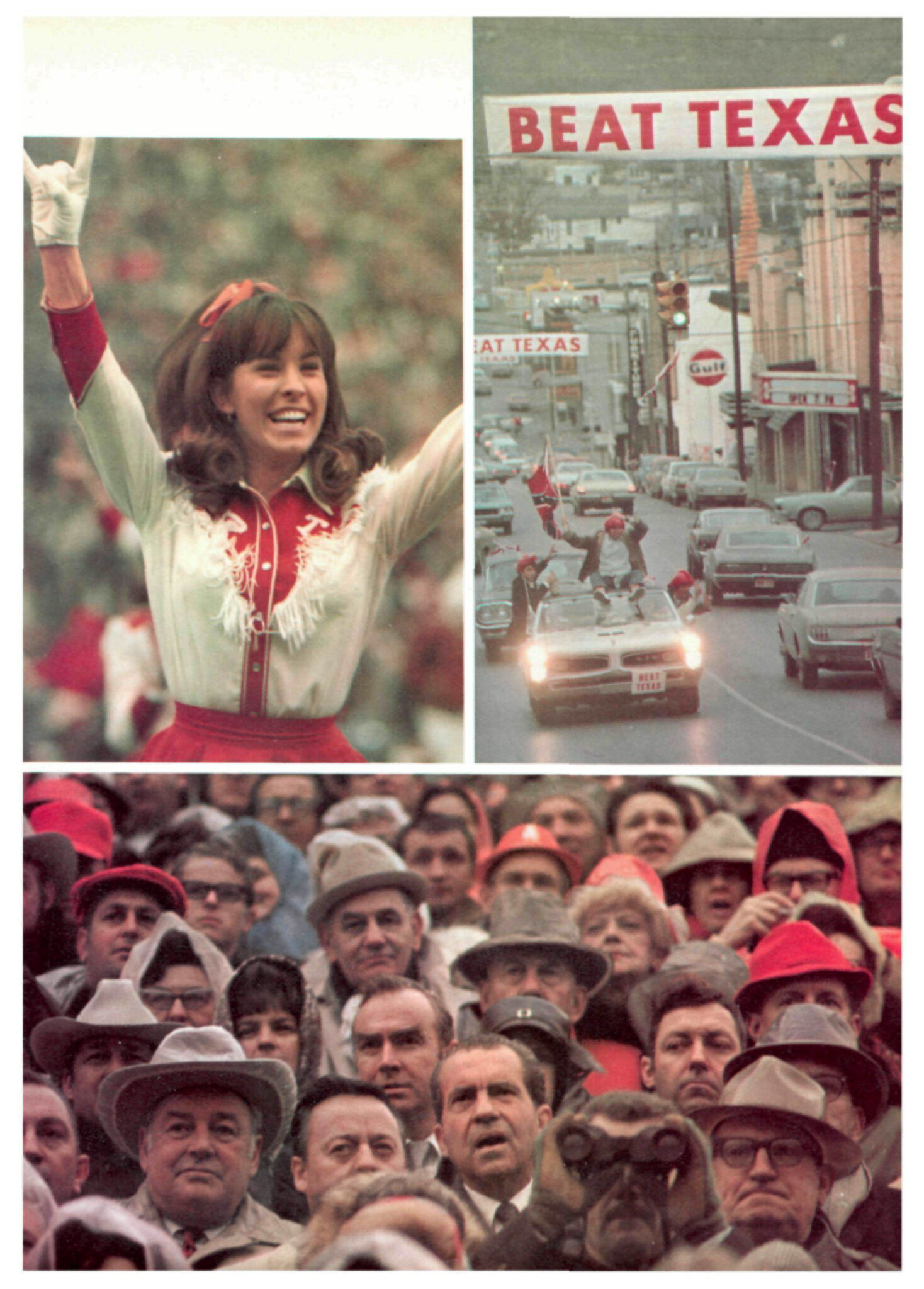

The visiting Texas team was No. 1-ranked and favored. Fayetteville, Hog Heaven, was cold, misty and raw that day. Just nasty. The city was bathed in red, decorated by tens of thousands of hog hat-wearing, hog-calling pigskin zealots who backed a similarly undefeated, 9-0 team, ranked second and primed to show up UT and the entire disdainful state of Texas.

Right now might be the first time in history that anyone ever declared Arkansas to have been ahead of the times. But in hindsight, I believe Arkansas was.

Long before endless streams of sports talk radio, trolling websites and cross-promoting 24-hour sports TV networks, an entire state was in pedal-to-the-metal “Gameday” mode, not for a few hours of screaming on cue for cameras as kickoff approached, but for a full week at least.

Passion, pride, fervor, hatred of Texas and desperate hunger for national respect... Arkansas had it all.

Even church signs notably warned or threatened the Longhorn “guests.” It all led legendary Texas defensive boss Mike Campbell to venture that visiting Arkansas was "like parachuting into Russia.”

But at least the folks at the Kremlin weren’t eager to fuel up on whiskey and then launch the empty bottles at the Texas sidelines.

Razorback Stadium, long before the traveling carnival of Herbie, Corso and crew was conceived, was the most spirited, cacophonous, ominous theater maybe ever to host a game as college football wound up its first century that gray day.

50 years later, the long lost Nixon plaque that he gave to Texas finds its way home. A recreation of the plaque was delivered to Chris Del Conte this week to honor the 1969 National Championship.

So there was that setting in the Ozarks. And when the Longhorns’ wishbone — which had throttled 18 straight opponents — took only two snaps to begin stumbling, bumbling and fumbling, Arkansas quickly jumped to an easy 7-0 lead. Nobody in the Texas camp thought this would be just the first of six turnovers by the previously almost perfect Steers.

The rest really is, well, history.

Arkansas led 14-0 after three quarters. Late two-touchdown leads in that era were regularly filed under "insurmountable."

But James Street, the greatest swashbuckler UT had produced since Bobby Layne, scrambled away from a big pass rush on the first play of the last period and outran faster Arkansas players for a 42-yard Texas touchdown. Before you could say "Darrell Royal," Street scored on a two-point conversion to pull UT within six points of the Hogs.

DKR, never one to leave stones unturned, had told Street on the bus ride to the stadium what play to run should the Horns need a two-pointer. Done.

Arkansas answered with a drive that seemed destined to make Street's heroics a moot eight points.

But on third down at the UT 7-yard line, Arkansas committed a fateful error, the biggest by far in the program's history.

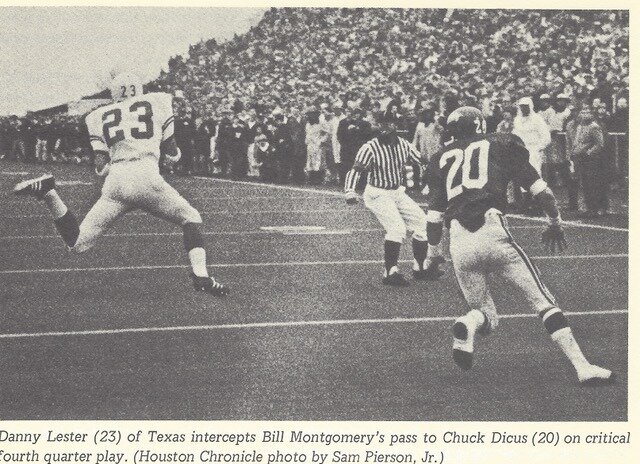

Instead of playing it safe for an easy field goal and a two-score advantage, the Hogs' splendid Texan quarterback, Bill Montgomery, sailed a pass into the end zone. Defensive back Danny Lester snuffed the gamble with a pick that buoyed the Horns' hopes.

Moments later, Texas was back on life support, it seemed.

Third-and-3 at its own 43 with under five minutes to go, it was UT's turn to gamble. What followed was for many years the defining play in Longhorn history and one that certainly lives on today as, at the very least, one of the two biggest plays in school record books.

It was "53 Veer Pass," as unlikely a call as a crushing wishbone team could dial.

Perfect pass by Street, perfect catch by Randy Peschel, missing four Hog hands by centimeters. Forty-yard gain and new life.

Koy then weaved and smash-mouthed 11 huge yards to the 2-yard line. Jim Bertelsen crashed in and cashed in on the next play to tie it up. Third-team quarterback and stellar holder Donnie Wigginton coolly snagged a high snap and the aptly-named ace kicker, Happy Feller, gave Texas a 15-14 margin.

Okay, some more "the rest is history."

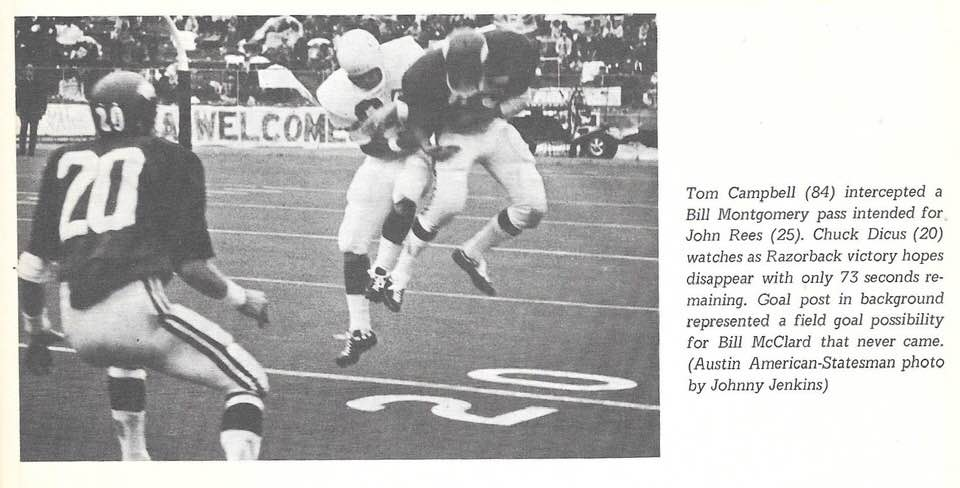

Defensive back Tom Campbell, the twin of defensive end Mike and son of Coach Campbell, stole the ball from the waiting hands of UA's John Rees, deep in Texas territory with under one hundred ticks to play.

On a day when not a damn thing went right for three quarters, Texas raked in all the chips at the end.

Richard Nixon handed a national championship plaque to Royal and captains Street, Koy and linebacker Glen Halsell inside a jubilant Texas locker room. Now the Longhorns were going to get to leave "Russia," only to be mobbed by ten thousand fans at the smallish Austin airport a few hours later.

Meanwhile, when the final gun mercy-killed Arkansas, all my family members in San Antonio were screaming, jumping and hugging, the kind of scene going on in a zillion homes filled with burnt orange hearts.

A mile away, my best buddy Morris — who would enroll as an Arkansas freshman in a year-and-a-half, was not in a joyful mood. But two hours later, he and I would be side-by-side in the stands, again pulling for the same team, as our Lee High Vols came back to beat Seguin in the state quarterfinals.

I stayed quiet about the earlier contest, knowing I wouldn't have wanted any wisecracks or boasts had the tables been turned. The shared victory for our school set up Lee for the following week's historic first high school game in the Astrodome and a thrilling 21-18 decision over Beaumont Hebert for a ticket to the state finals.

Good, good times.

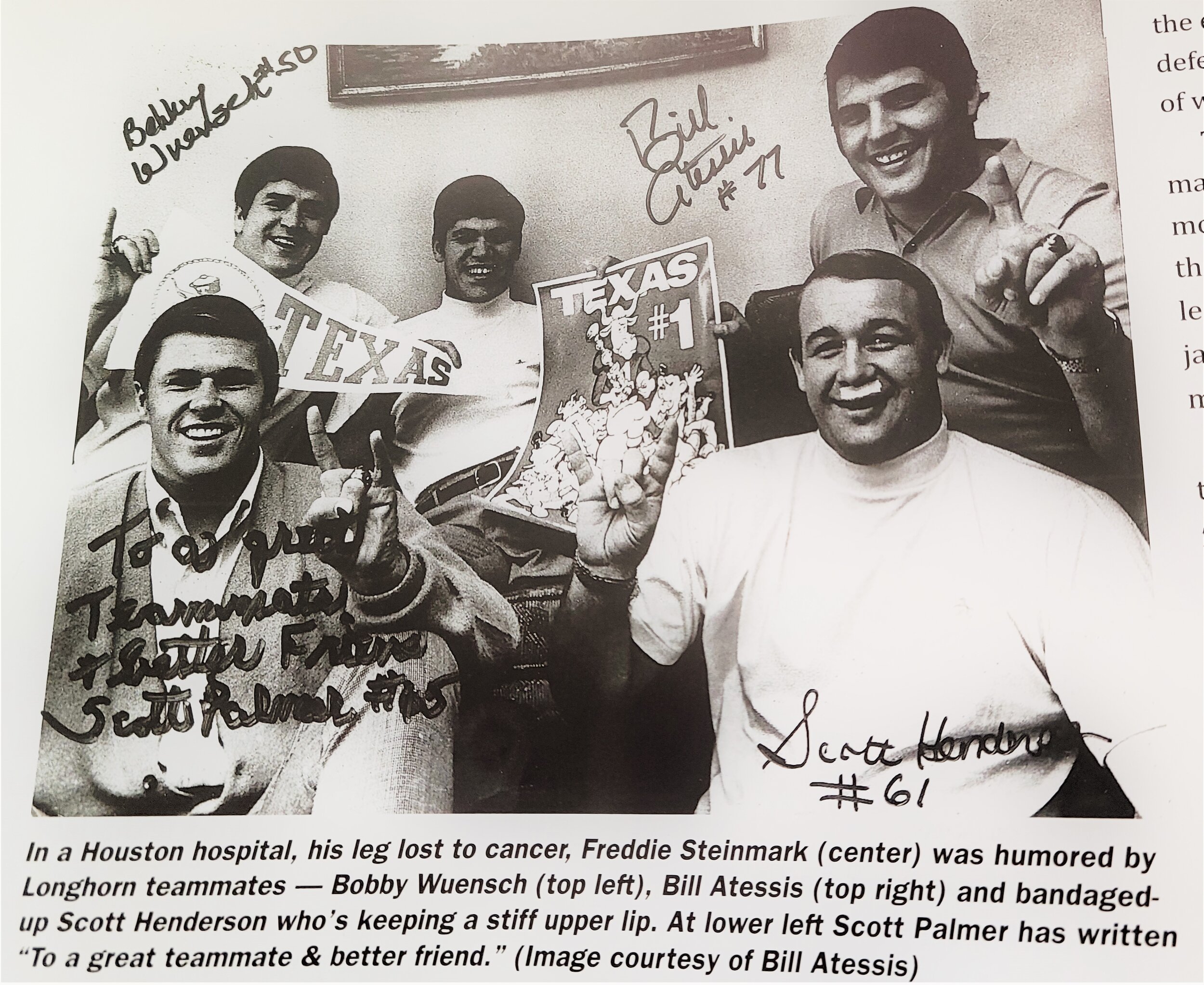

But less than a week later, safety Fred Steinmark, though strangely hampered by lack of speed, had saved a sure Arkansas game-clinching touchdown pass by alertly tackling a speeding Arkansas receiver en route to wide open status, had his cancerous left leg amputated. He would become a national symbol of courage and optimism and would make it to the Texas sidelines on crutches in under three weeks to inspire his teammates in a spine-tingling 21-17 Cotton Bowl victory against Notre Dame on Jan. 1.

Tragically, Steinmark succumbed to cancer the next year. His legacy lives on with all UT players today. A lingering sadness remains with his family members, teammates, friends, loved ones and fans.

If you've not read the excellent Big Shootout prologues, game accounts and epilogues by author Terry Frei and author/documentarian Mike Looney, you're missing out. Both noted the sportsmanship, kinship and fellowship that Texas and Arkansas players felt that day, have lived with and even rekindled together.

It seems unfathomable today that there was no wild celebrating nor whining, no trash-talk or misconduct on such a big stage with unprecedented stakes. But those were different times.

Today, college football players wag fingers or gesticulate wildly and celebrate routine tackles, catches or pass breakups. Even when trailing by 27 points. By no fault of their own, they are almost universally referred to by their coaches as "the kids," and perhaps treated as such.

But those Longhorns and Razorbacks, back then, they were men. They worked hard, played hard and dealt with the draft for service in Vietnam during the week of the biggest game. They handled gridiron outcomes with grace and class.

Almost to a man, they became very successful in their chosen fields.

The work done by the likes of Frei and Looney leads me to suspect that perhaps the loss has stayed with Arkansas players and followers even more than has the victory been branded into Texas mindsets. It was Royal himself who once mused that the losses stay with you more than the wins. Winners expect to win. And losses don't go away.

This win, though, was and is part of the players and fans who were there, watched or listened.

That is certainly so for this writer.

Everything about it seems imprinted into the brain files. And in December '69, I didn't dream that eight years later I would be working as an Austin radio sportscaster, hosting the postgame Longhorn Locker Room Show and getting to interview the legendary, unbeaten (20-0, forever) Street in my first two weeks on the job.

When James — stupidly called "Jimmy" by ABC's Chris Schenkel on the Big Shootout telecast often replayed in muddy film on the Longhorn Network — yelled at me by name across a crowded watering hole a few days after I had met him, I wanted to pinch myself.

Later, I couldn't wait to call my dad and tell him who had bought me a drink.

Soon, I was fortunate enough to write for Street's "Orange Power" magazine several times. Boy, I needed that first paycheck I got from him. But before I cashed it, I had to take it to the Xerox machine and copy it.

I mean, James Street had signed it.

Many, many years later, I would marvel at my good fortune to chat up Worster for an hour before his induction into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame. I listened intently as we talked football and he told me how his old teammates had helped him through the tough times when a hurricane destroyed his home — back in good ol' Bridge City — forcing him to live out of his car.

Three years ago I contacted Dr. Ted Koy and asked him if there was any way he might find time to visit my sports media class at Texas State University, to reminisce about the Big Shootout, little big man Freddie Steinmark, life in the NFL and as a long-time veterinarian. Of course he could, and did. The UT Communication major sure knew how to wow young communicators-in-training.

And their instructor.

After I sent Ted a thank-you note for his visit and kindness, I received a note in my mailbox. It was from Ted, thanking me "for the opportunity to meet with the fine young people.”

I don't know if they even still make people like Ted Koy. I really don't. But I sure hope so.

All these years and I have a wealth of great memories connected to the '69 champs and The Big Shootout. And they're still arriving.

My ol' buddy Morris, long a proud Arkansas grad living in the Fayetteville area, recently made a phone confession, just shy of a half-century after the fact. When he and I were scheduled to meet for our high school's crucial game a few hours after The Big Shootout, Morris apparently made kind of a grand exit from his parents' home.

"I was still so stinkin' mad," he recalled, describing the force with which he hit the back screen door en route to a cheeseburger and then the game.

His folks howled, he said, and it wasn't with laughter.

"How bad was it?" I asked.

Now, a cool 50 years later, Morris allows himself a cackle. "That baby was flyin'!"

Write to Larry Carlson at lc13@txstate.edu