UTNY: Four Longhorns helped Namath back up Super Bowl guarantee

By LARRY CARLSON Feb 3, 2019

Imagine four players who sweated and soared on a college championship team together, then moved on to one pro team and played key roles in a Super Bowl win, against the biggest odds there will ever be. The fairy tale turned into history a half-century ago this year, when the New York Jets, dubbed UTNY by some Texas scribes at the time, captured Super Bowl III.

A lasting image in American pop culture is a photo and video clip that defined a generation of football and its fans. Joe Namath, trotting off the Orange Bowl turf, wagging a "No. 1" index finger into the Florida twilight, palm trees just beyond the end zone. Joe Willie's triumphant digit might as well have been a middle finger directed at not just the soundly-beaten Baltimore Colts but the old guard NFL and authority figures everywhere.

Namath, just 25, had backed up his outrageous guarantee that the youthful Jets would beat the vaunted Colts, favored in Las Vegas by 18 points. Namath had done it with a heaping helping of Texas-sized talent and moxie from a quartet of UT-exes.

The irony of the moment was not lost on followers of Texas and Alabama football.

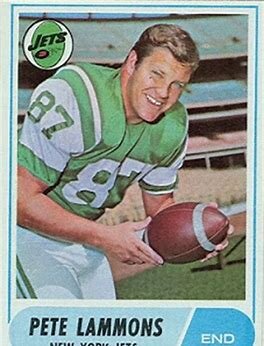

Pete Lammons (87) was one of four Longhorns who helped the Jets pull off one of the greatest Super Bowl upsets ever 50 years ago.

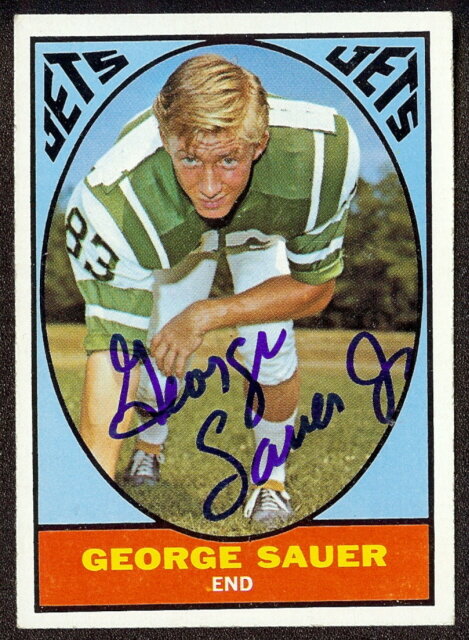

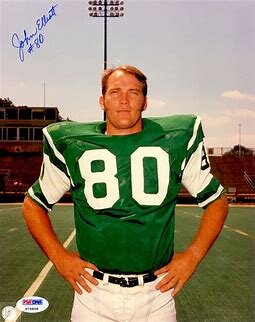

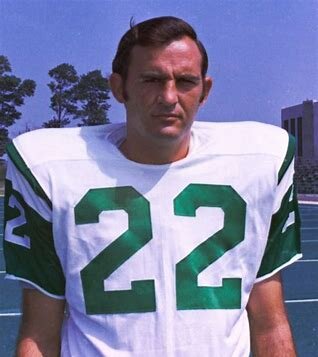

Four years and a week earlier, the Longhorns, with tight end Pete Lammons, wide receiver George Sauer Jr., defensive lineman John Elliott and safety/quarterback Jim Hudson as key contributors, had taken down Namath and the Tide, 21-17, in the Orange Bowl's first night-time primetime matchup.

Hudson, who seldom took snaps at quarterback all year, had even rotated in to loft a 69-yard touchdown bomb to Sauer. The burnt orange defense, led by the non-pareil linebacker Tommy Nobis, had stuffed Namath and Alabama just inches from the goal -- four running attempts from inside the six -- to preserve the big win.

Alabama had already been crowned as 1964 national champs but bragging rights and the Orange Bowl trophy went to Darrell Royal's Texas team, which had barely been denied a shot at back-to-back national titles because of a 14-13 mid-season loss to Arkansas. The Horns and Bear Bryant's Tide both finished 10-1.

No gazer into a crystal ball or wily pro scout could have foreseen what would unfold in four years. Namath jilted the NFL draft for a record payout from the still-wobbly AFL, then quickly became a star at Shea Stadium and in Gotham's late-night bar scene.

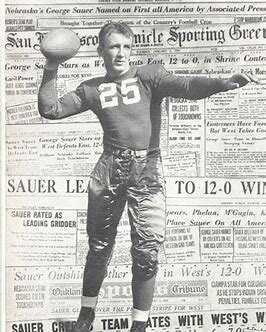

Sauer, son of George Sauer, Sr., (a member of Green Bay's 1936 NFL champs, a SWC Coach of the Year at Baylor in 1950 and then the director of player personnel for the Jets) would do his own bit of shocking football betrayal. He became the first Longhorn to ever skip a year of eligibility to bolt for a pro contract.

https://texas-lsn.squarespace.com/george-sauer-conflicted-soul

DKR, stunned and angered, henceforth banned Jets scouts from the UT premises.

First Hudson, then Lammons and finally Elliott joined Sauer and the Jets. All quickly ascended to starting jobs. Like most of their fellow starters aside from Namath, their salaries of less than $25k reflected the times when players still took offseason jobs and scrapped hungrily for playoff money that could basically double their annual football earnings.

"Broadway Joe," as Namath had instantly been dubbed by Manhattan reporters, became a symbol of success, excess and a measure of innocuous anti-establishment bravado. The white shoes, the slightly shaggy hair and a shrugging lack of awe for the old-school football ways, all made Namath the hottest commodity in professional sports. Starlets wanted to be with him and teenaged boys across the land — later captured by the fictional Kevin Arnold of the TV series, "The Wonder Years," — idolized him, ditched their regional teams, slapped Jets pennants on their bedroom walls and savored any Jets appearance on NBC's Sunday AFL lineup.

Namath and the Jets were featured in the infamous "Heidi" game prior to taking on the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III.

And the '68 season featured the infamous "Heidi" game in which millions of viewers missed a wild Raiders comeback victory over New York when the network automatically defaulted to Disney fare while Ben Davidson and Namath were still doing battle. But the New York team, still dwarfed by its crosstown big brother, the Giants, made it to the AFC championship game. There they avenged the Heidi nightmare by ousting those big, bad Raiders. That, in spite of losing Hudson and Elliott because of separate incidents that led to their ejections after what officials deemed to be excessive protests.

But now the UTNY boys plus six more Texans (most notably, future NFL Hall of Fame wide receiver Don Maynard from old Texas Western and offensive tackle Winston Hill of Texas Southern) would be playing in pro football's biggest game. At least one New York writer had wondered before if maybe having ten Texans on a roster was "like too much pepper in the stew."

But followers of football in the Lone Star State already knew that there's no such thing as too much heat in a great batch of chili.

Since Green Bay had embarrassed Kansas City and Oakland in the first two editions of the new NFL vs. AFL season-ender, nobody had much thought of the matchup as anything resembling "Super." Oddsmakers figured the junior New York team had essentially no chance to win against the mighty Colts.

But Namath was hardly intimidated by the scoffing and famously remarked a few days before the game that "...we are going to win Sunday. I guarantee it."

The media hype surrounding the game suddenly exploded. As writer Bob Lederer notes in his 2018 book about the Super Jets, "Beyond Broadway Joe," Pete Lammons had been voicing similar matter-of-fact confidence to his teammates. The East Texan from Jacksonville had told Jets head coach Weeb Ewbank to stop showing the squad so much game film on the Colts.

According to Lammons, it was making the Jets over-confident.

Sunday came and the TV audience was enormous for this "Lions versus Christians" mismatch. Half of the viewers no doubt were hoping for a game, the other half hoping Namath would be devoured by the proud Baltimore club.

History shows the Jets winning, 16-7, in a game pretty much controlled, wire-to-wire, by the upstarts.

The Colts were ready to take away any Namath-to-Maynard bombs and they succeeded in what can generously be categorized as a pyrrhic victory. Maynard was shut out on catches for the day. But Sauer, a route-smith and all-star receiver on the other side, turned single coverage into ball control and ultimate victory, catching eight passes and relentlessly, along with Matt Snell's pounding runs, moving the chains and draining the clock.

Lammons was Lammons. The man once described by a Longhorn position coach as having "a sweet smile and a mean disposition," caught three balls and delivered bruising blocks that paved the way for the Jets' game plan.

The New York defense never gave Baltimore's league MVP quarterback Earl Morrall a chance. He and fellow crewcut football god, Johnny Unitas (who was called on late) suddenly looked not just outdated but tired and unprepared for what the Jets delivered.

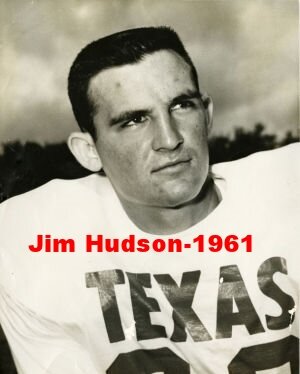

Jim Hudson developed into a standout safety with the Jets and drew the assignment in Super Bowl III of covering Hall of Fame tight end John Mackey.

Hudson, a superior athlete from the Rio Grande Valley city of La Feria, had turned down John Wooden's offer of a UCLA basketball scholarship to play football at Texas. He was good but never great in Austin, splitting time at quarterback and in the defensive backfield.

But his speed, size (6-2, 210) and physical play made him a standout strong safety in New York. Going into Super Bowl III, Hudson had drawn perhaps the biggest challenge on either side of the ball He would be largely responsible for preventing All-Planet tight end (and future Hall of Famer) John Mackey from adding to what — since the early retirement of Cleveland's peerless running back Jim Brown — was the glossiest, showiest highlight portfolio on NFL Films' highlight reel.

With the exception of one good play by Mackey in the early going, Hudson won the day. He held Mackey to just three catches for 35 yards and made a key interception to end the first half when the Colts tried trickery to kill New York's growing confidence and momentum. The 7-0 intermission lead would swell to a 16-0 advantage before Baltimore, at last, got on the board with under four minutes to play.

As for Elliott, the rangy 6-foot-4-inch defensive who hailed from the map-speck Big Thicket community of Warren, he launched his All-Pro status that Sunday in Miami. On the Colts' first play from scrimmage — when Hudson lost to Mackey for the only time that day — Big Bad John (as he was known on Jets radio broadcasts) pursued and ran down the swift tight end and knocked him out of bounds after a 19-yard pickup.

Later on that drive, Elliott foreshadowed the Jets' toughness, talent and knack for adjustments that would culminate in what is still the biggest upset in Super Bowl annals.

According to Lederer in "Beyond Broadway Joe," Elliott pulled off a "superhuman defensive play" by fighting off not one, not two but three blocks and then made a solo tackle on Colts running back Tom Matte for just a one-yard gain, And when he wasn't making tackles, Elliott bedeviled Earl Morrall all the livelong day.

Namath and the Jets, fueled by the four Longhorn stalwarts, made history that day. The kind that lasts. They changed pro football and pushed the sport toward the highest step on the sporting and financial ladder for those players, viewers and fans who would follow and who enjoy NFL football today.

Some of us still remember the day Joe and the Jets backed up the braggadocio and created a little sports miracle. In bigger picture news, a hulking but now haggard Texan named Lyndon Baines Johnson, eroded by the pressures and publicity surrounding the war in Vietnam, had buckled and decided not to represent his party in the '68 presidential race.

When the sun set on the Super Bowl that January 9, 1969, the President would have less than two weeks left in office and under five years to live.

On the sunnier side of news, in the sporting world, the Jets were kings and a University of Texas football program that had suffered through three straight 6-4 regular seasons, was back. The Horns had finished the '68 season with nine straight wins, including a 36-13 annihilation of Tennessee in the Cotton Bowl. Twenty-one more consecutive wins would come, as would two national championships amid five more Cotton Bowl trips in a row.

Now, 50 years have passed. Many of the triumphant Jets players have died, including all but Lammons from the flinty UTNY gang. The game propelled Namath to a Hall of Fame career while he was also making Hollywood movies and selling an autobiography entitled "I Can't-Wait Until Tomorrow...'cause I get Better-looking Every Day."

The chapters sported cocky and catchy titles such as "I like my girls blonde and my Johnnie Walker Red", and "Broadway Joe" will forever maintain legendary for his guarantee and ensuing heroics. But even Joe now stands tall not against the blitz but by facing reality and Father Time, pitching Medicare benefits to fellow seniors via television ads.

The New York Jets have never returned to the Super Bowl. But for one magical afternoon back in '69, the Jets really were super.

It was guaranteed.

For more information on Lammons, Sauer, Elliot, and Hudson click on the link below.

https://texas-lsn.squarespace.com/longhorns-lammons-sauer-elliot-hudson-and-the-jets

Write to Larry Carlson at lc13@txstate.edu