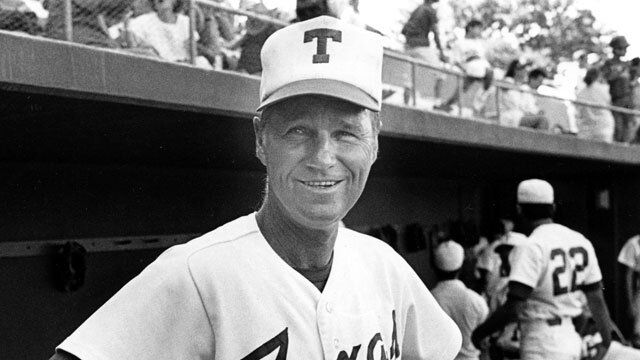

Coach Cliff replaced Bibb Falk as the head baseball coach.

Gustafson is one of a few college coaches who both played in the College World Series and coached it.

Cliff finished his Longhorn college career at Texas with a .308 average. Cliff Gustafson had one year (1953) pitching in the professional West Texas-New Mexico League. He was a good enough player to play for the pro’s but a broken leg cut short his professional career. Gustafson says that as a player for Coach Falk he learned to play good sound defense, develop pitchers, and capitalize on other people’s mistakes. “When I was playing for him I heard him say many times that most games are won on other people’s mistakes.” At the high school level Gustafson won 11 district championships and 7 state championships.

Darrell Royal, the athletic director in 1968, gets credit for hiring Cliff. Darrell Royal offered Gus the job over the phone. When Royal asked how much he was making at South San, Gustafson was embarrassed to tell him that he was making a lofty sum of $11,500. So Gus said to Royal I am making $10,500. Royal offered him the same amount to come to Texas.

Years later, Royal was asked if he ever dreamed Gustafson would be so successful. He responded, "Hell, no, If I'd known that, I'd have gone down there in my car to hire him instead of calling him on the phone."

His peers respected coach Gus. The Arizona State Coach Jim Brocks in 1981 said about Gus, "is the nicest guy in college baseball. Gustafson is a nice guy who wins, and usually, those two things are mutually exclusive."

His coaching style focused on sound pitching, sound defense, and playing the percentages.

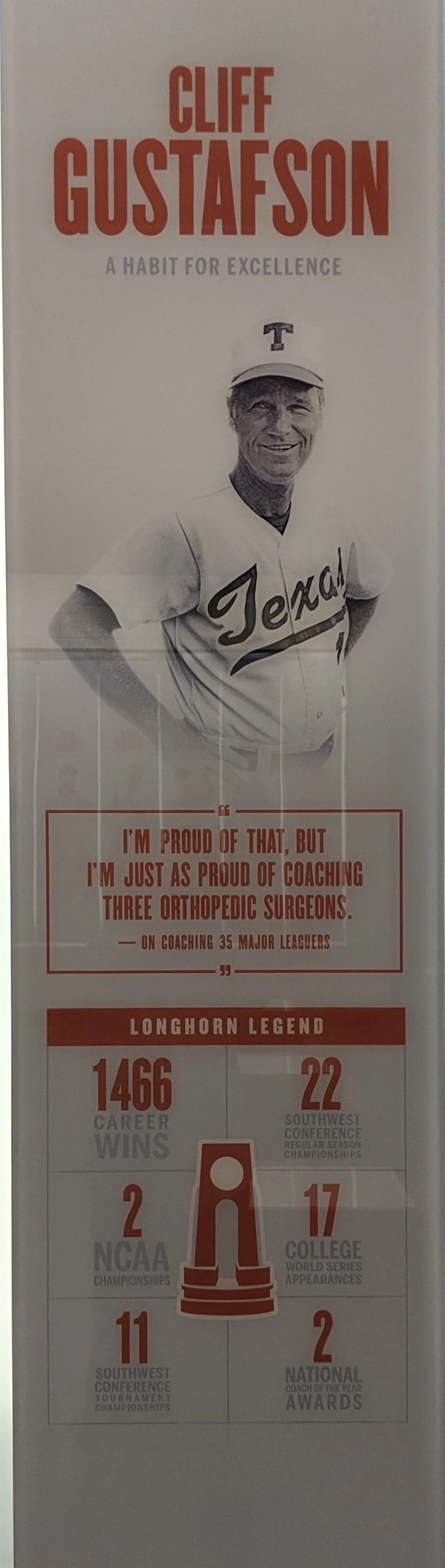

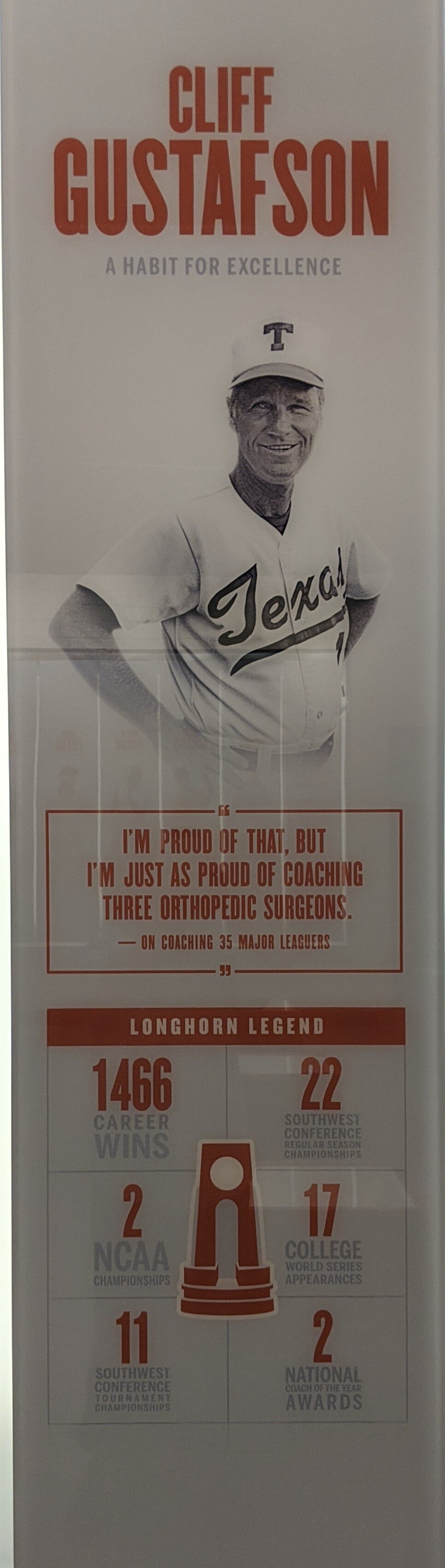

Gus's record includes:

22 Conference titles

11 SWC Tournament Championships

2 National Championship -( 1975 and 1983)

NCAA record 17 appearances to the College World Series

Won lost record of 1466-377-2 record

Member of the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame

1994 inductee into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame

1998 received the James Keller Sportsmanship Award

Coach makes decisions during his coaching years by statistics and percentages.

Gus won because he had an eye for talent, a recruiting moral compass,work-outs that preached repetition as the mother of all baseball skills, and a style of play called GusBall - gambling, run-a-bunch style in which nobody worries about hits. His teams won by using discipline and patience at the plate. No team on any level took more pitches than Texas. Many times the Horns had more runs than hits. In 1981 against Baylor, the Horns scored seven runs on one hit in the last inning to win 13-6. Recruits loved Gus's down-home and upfront interaction, but he was not happy when a recruit recanted a promise, so Gus held his moral ground. A high school catcher from California, Jeff Hearron, promised to come to Texas, so Gus moved on to recruiting other athletes in other positions. Gus and Jeff were talking on the phone when Jeff said he might go to Arizona State. Hearron told Gus he was going to "pray over his decision." Gus responded, "So am I, only I'm going to pray that the Lord will forgive you for being a liar." Hearron joined the Longhorns Gus hated road trips and change so much he would massage the baseball schedule to get as many home games as possible. One year The Horns played 38 of 48 regular-season games at home. Sometimes changes were even worse than travel. Someone threw away his coffee cup after the handle broke. He was furious at losing a cup that had served him well for 19 years. Super glue could have fixed his prize possession. Thirty-five of his players made it to the majors, including Boston's Roger Clemens and Houston's Greg Swindell, but he says, "I'm just as proud of coaching three orthopedic surgeons." Gustafson doesn't just coach; he teaches. Longhorn Shortstop Spike Owen was asked if Gustafson had ever done anything to help his game. "Naw, not really," says Owen. "All I can think of is that I used to take two or three little crow hops before I'd throw. He got that out of me in a week. My footwork deep in the hole was terrible, and he fixed that. He changed my throwing from over the top to three-quarters. He changed my grip on the bat entirely. Then he changed my stance. So he hasn't changed me much." Pitcher Calvin Schiraldi says, "All Coach Gus is, is a genius." Dodger pitcher Burt Hooton, says, "I've always wanted to be just like Gus, but so far the only similarity is we're both bald." Howard Richards, a member of the Texas Board of Regents, says, "I wish we could clone Cliff and let him coach every sport." Athletic Director DeLoss Dodds, before they parted ways, said: "If you took the best parts of all coaches, you'd get a Gus."

Gus Ball

GusBall was invented and mastered by Coach Gus. Other coaches feared the Longhorn’s ability to win when they don’t seem to deserve it. It is a successful technique of hanging on until the other team defeats itself.

Like a master chess player, baseball nurtured Coach Gus's competitive spirit, and he was able to master most other teams as the head coach of the Longhorns. But like DKR in football at the end of his career, he said, "the only bad thing is that the agony of defeat sure lasts a lot longer than the ecstasy of victory. It shouldn't be that way." Royal resigned, citing this as one of the reasons he left coaching. Cliff Gustafson left for many more complicated reasons.

By Kirk Bohls

Posted Sep 24, 2016 at 12:01 AMUpdated Sep 25, 2018 at 8:55 PM

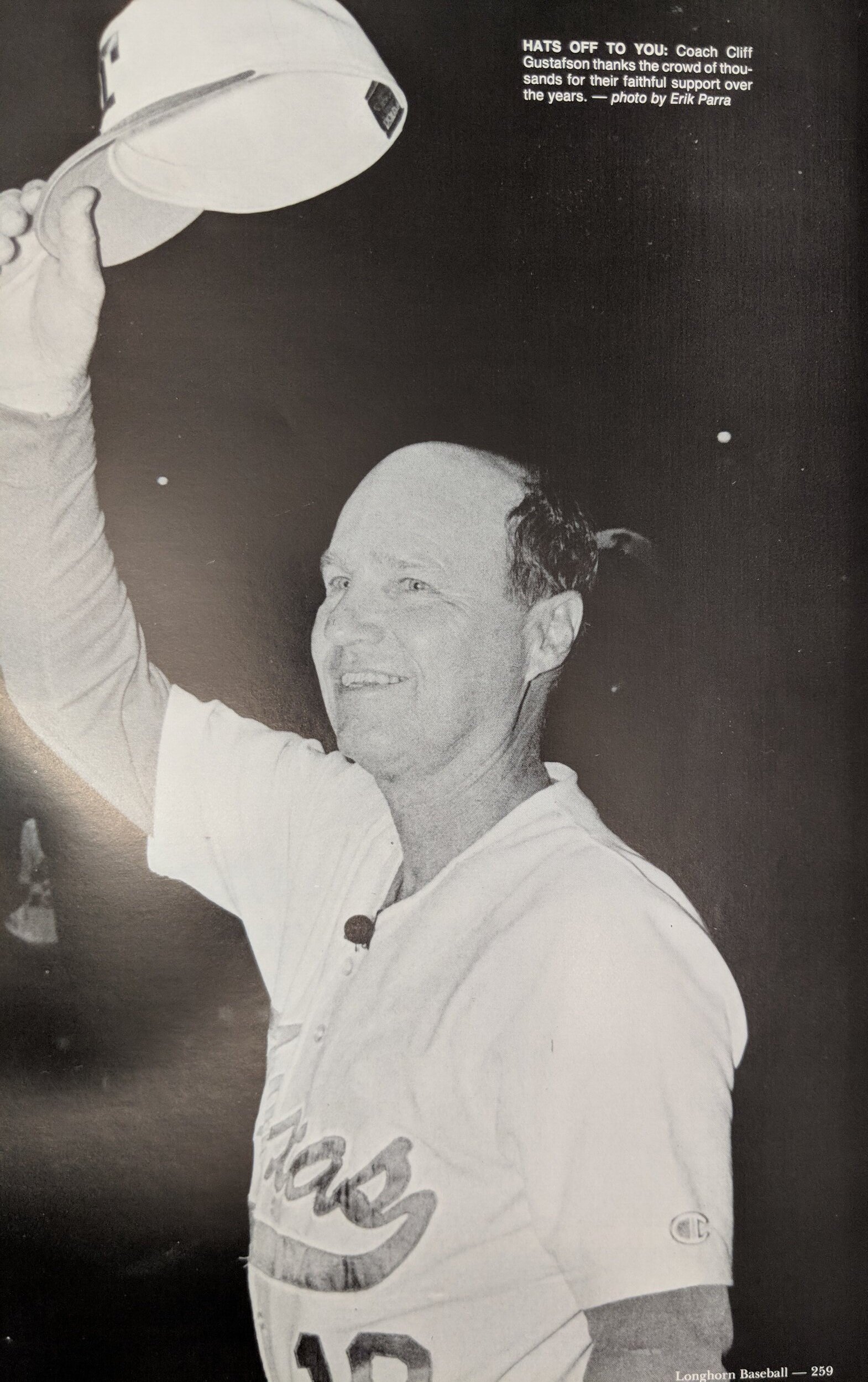

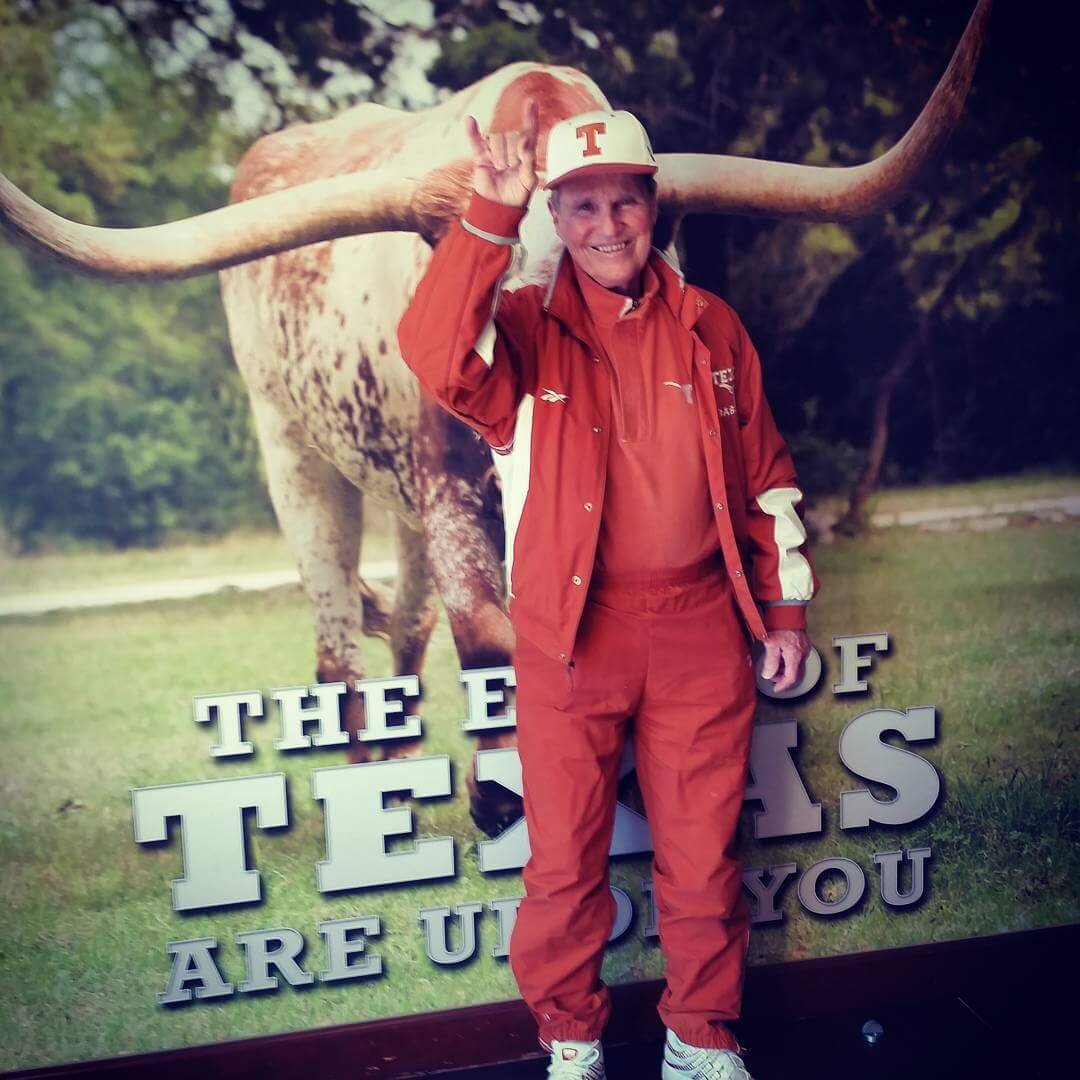

Austin celebrated Cliff Gustafson last week, and even the city’s historically snarled traffic didn’t deny him an easy trip down memory lane.

The South San Antonio high school baseball coach, who lied to Darrell Royal in 1968 by saying he was making $500 less than he really was so as not to scare off Texas’ athletic director, eventually accepted the Longhorns job and became the winningest coach in Division I baseball.

Of course, Gus said he was so skeptical when Royal first called, he almost said, “Yeah sure, and this is Roy Rogers.”

More than a half-century later, Gustafson — who attended Friday’s dinner honoring him as a National College Baseball Hall of Famer with his new wife, Ann — joins Augie Garrido, Rod Dedeaux, Jim Brock and Ron Fraser as the five best coaches in college baseball history, in my opinion.

There were laughs and toasts and even some winces. Brooks Kieschnick reminisced about throwing 172 pitches to beat Oklahoma State in a College World Series game, to which someone in the crowd bellowed, “Is that all?”

Gus wasn’t much on pitch counts or excuses for losing or long hair. But he took baseballs home to stitch them up and pored over his stats and scorebooks and lineups in between nightly bowls of Blue Bell vanilla. He’d hold practices from 1 o’clock until way past dark, and he drilled his teams incessantly on everything from the squeeze bunt to hitting the cutoff man. “It may come up in a game,” he would tell his exhausted players.

He gave his players the take sign almost automatically on 2-0 and 3-1 counts, although that didn’t apply to Keith Moreland. Why? “I didn’t look (for a sign),” he said.

And Gus won. All the time. An amazing 1,427 times for a .792 winning percentage that still ranks first among Division I coaches. He won with pitching and defense and balk plays and double steals and bases-loaded walks. He won so much that nemesis Gary Ward of Oklahoma State finally told him he knew his secret and showed up with custom boots to the CWS press conference. Gus calmly rolled up his pant legs to show off his boots and said, “Yeah, but Gary do you have your number on yours?”

No. 18 was No. 1 with Texas for a long, long time.

Gus coached when going to Omaha was the standard. He went there 17 times in 29 seasons. He won there twice. Could have won a half-dozen or more. One time he finished second in 1989, his team had no business even being there.

He followed Billy Disch and Bibb Falk and made Texas better.

Assistant coaches, opposing coaches, umpires and former players, all gushed about Gus and their memories of him a week ago:

Gene Stephenson, who won 1,837 games, cost Texas a national title when his Wichita State team knocked off a Longhorns team in 1989 that had two great players in Dressendorfer and hitting star Scott Bryant and little else.

“We came here in 1982 for a doubleheader. We never scored a run, and I was so furious,” Stephenson said. “I kept wondering why weren’t we hitting these guys. He threw two weak, little pitchers named Roger Clemens and Calvin Schiraldi.

“He’s the classiest coach I’ve ever been around.”

Gustafson, who turns 84 next week, never would say his 1975 team that won his first national title was his best. Until the night the Longhorns beat South Carolina and the players got him to admit it. “When (shortstop) Spike Owen played, he was the greatest I ever saw in college,” he said. “And Burt Hooton was the greatest college pitcher I ever saw.”

The Longhorns were set to play TCU in Fort Worth one day, and Gus, per tradition, hit the hay long before everyone else in the same hotel room.

Long-time assistant coach Bill Bethea and staff stayed up for a few more rounds of 42 before shutting it down for the night.

A war movie on the television punctuated the spirited conversation without interrupting the domino game. During one scene, a group of Navy frogmen swam up to a pier and came across a bomb inscribed with Japanese words.

Pitching coach Clint Thomas squinted at the television and wondered aloud, “What do you think that says?”

A voice broke the silence. From under the covers, Gus said, “Beat Texas.”

“He taught me the right way to play the game,” Clemens said.

Gus always had the strictest of policies and a hair code that didn’t exactly fit the times in the late ’60s. Long sideburns were out. Mutton chops were forbidden.

The late James Street was one of the first to test his coach. He didn’t worship Elvis Presley just for his blue suede shoes. Later, burly catcher Bill Berryhill also felt strong about free expression, particularly when it came to their wavy locks.

One morning, Berryhill arrived at the ballpark and noticed that his uniform wasn’t in his locker. He approached trainer Spanky Stephens, who told them to take it up with Coach.

“I don’t see the relationship between my ability to hit a baseball and the length of my hair,” Berryhill told Gus defiantly.

Responded Gus, “Well, in your case, we’re not going to find out.”

Freshman catcher Tommy Harmon became the leader on Gus’ first team in 1968 and then a long-time assistant, but his recruitment to Texas pre-Twitter lacked a bit of today’s drama.

During a series with TCU in Fort Worth where Harmon starred for Eastern Hills, Bibb Falk, Gus’ predecessor, saw him at the game and sidled over for a recruiting pitch.

“You want to be a Longhorn?” Falk asked.

“Yes,” Harmon said.

“You are,” Falk said.

Harmon has an even stronger recollection of a troubled situation years later when taskmaster Texas trainer Frank Medina, who was barely taller than a couple of Louisville Sluggers, approached Gus about a problem player. Medina’s brow was tightly knit.

“I got a player who’s a little bit lazy,” Medina told Gus. “Keith Moreland won’t do anything I’m trying to get him to do. He’s always last in the line. He won’t run. He won’t do anything.”

Medina had the perfect solution: Kick Moreland off the team.

“Frank,” Gus began, “I can find another trainer. I can’t find another All-American third baseman.”

One of Mike Anderson’s proudest moments came when the left fielder played a ball hit off the wall and held the batter to a single. Chest puffed out, he jogged into the dugout at the end of the inning. Gus promptly chewed him out. “You either catch the ball,” Gus said, “or you run through the wall trying to catch it.”

“You’ve changed our lives, Gus,” star hitter Doug Hodo said. “And we appreciate all you’ve done for all of us.”