WHEN TO CELEBRATE A LOSS.

As I learned in high school track, losing can be part of a winning formula. On a day I set a personal best time in the 100-yard dash, I finished last in the heat. As a 17-year-old boy, I was surprised that I was happy as the young man above, who finished 3rd.

It was an epiphany moment that helped me, over time, re-calibrate my definition of success. It is essential to celebrate your personal best performance in your race through life, even if you finish last. It is vital to the human spirit to smile and enjoy success even in last place- no matter the circumstances. In order to experience a fulfilling life, it is necessary for you to clear the cluttered path formed by those who judge from the top of the podium.

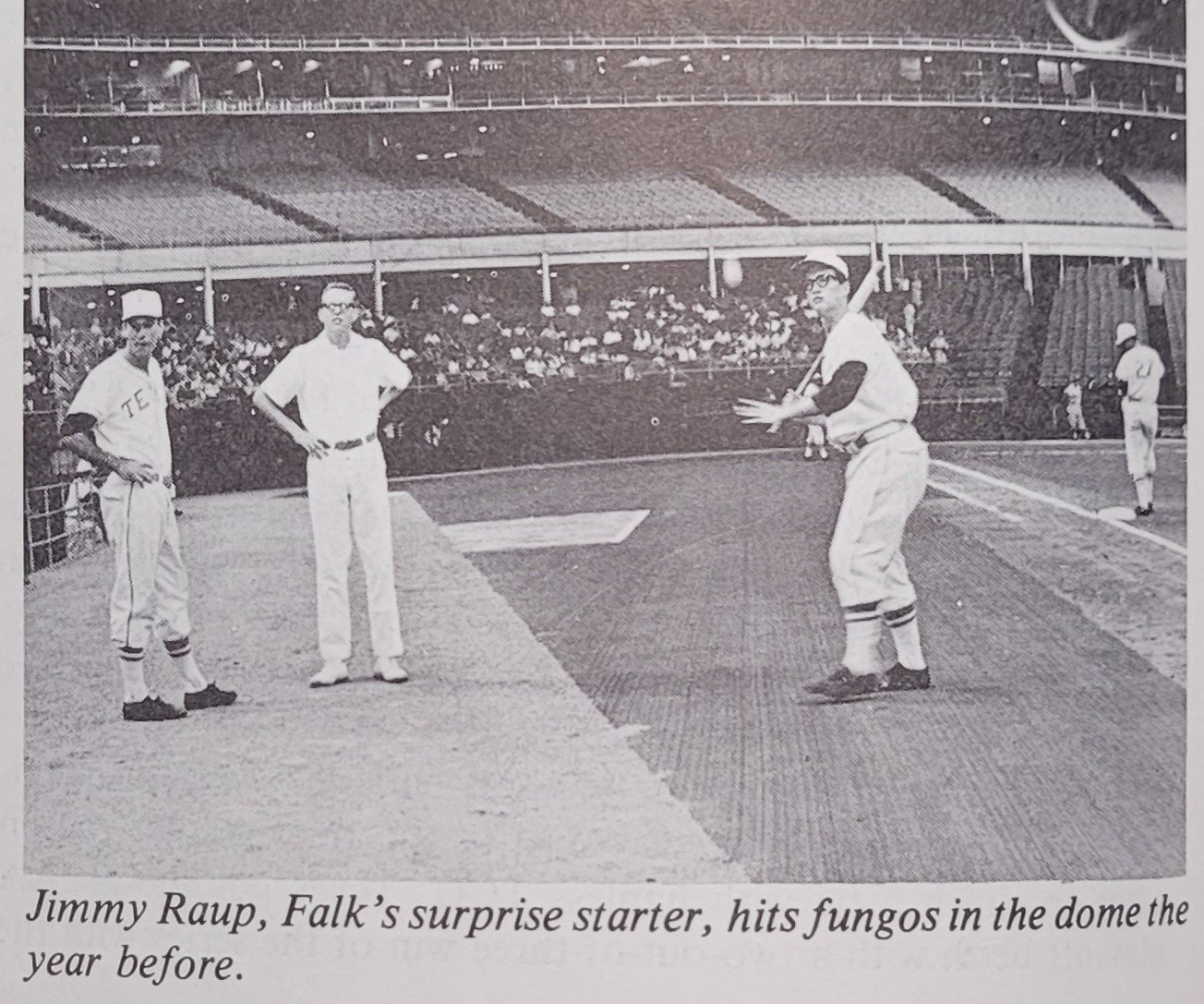

Longhorn pitcher Jim Raup shares an article titled “THE 27th OUT”—his story shares when to celebrate a loss. Texas missed a trip to Omaha, compliments of the Houston Cougars, and Jimmy Raup was the pitcher.

In the top of the 9th, Jimmy had two outs, two strikes on a Houston batter, and a 3-0 lead. Texas Lost!

Jim’s dream of winning the last game of Falk’s career and receiving an invitation to the NCAA tournament turned into a nightmare finish. The Longhorn season was over. But in his sorrow, Jim realized he had just pitched his best game as a Horn and chose to celebrate the loss, saying, “Most important, I learned and believe earnestly that there is no disgrace or dishonor in failure if one has tried his hardest to succeed. Disgrace is giving less than one’s best effort or allowing failure to kill one’s will to compete.”

A special thank you to one of Horn Sports' own, Coach Jim Raup, for letting us share this story with our members and all Longhorn fans. This is an incredible read for those that enjoy Texas baseball, history, and The University of Texas.

Hook 'Em.

The 27th Out

by Jim Raup

Jim is in the middle row, second from the left.

1967 - front -Thurman, Hunt, Lackey (manager), Enderland, Johnson, Scheschuk, Roberts- middle- Fell, Raup, Gressett, Vaughn, Peebles, Bracht, Scott, Hale (trainer) -back- Falk, Clements, White, Smith, Brown, McBride, Moore

Jim Raup

Baseball is a cruel game. I have heard that venerable adage my entire life as a baseball player, coach, and fan. Usually, the statement is spoken as a universal truth by a losing manager or coach or by a player who did not succeed when success mattered most. I considered the phrase to be avoidance of acceptance of personal failure: if baseball indeed is cruel, then the Game must have caused the bad result, not any personal failure by team or player. For me, baseball was a simple game with no inherent cruelty: get 27 outs and score more runs than the other team. One of the defining moments of my baseball life caused me to reflect, however, on heart-breaking events inextricably interwoven with the 27th out and to wonder if there is truth to the adage that the Game itself is cruel.

Side-note - Jim says “the student trainer in that photo is Terry Hale, who was a very close friend. He was killed in Viet Nam. He was such a great guy. He was a Marine lieutenant and stepped on a land mine. Falk called me at home to tell me.”

On May 19, 1967, the University of Texas Longhorns and the University of Houston Cougars prepared to play the third and deciding game of the NCAA District Six playoff series. To the winner would go a berth in the College World Series in Omaha. The teams had met in the 1966 District Six playoff, and Texas advanced after a 2-1 series win. For Texas, trips to Omaha were commonplace, but Houston was a relative newcomer to NCAA playoff baseball and had been to the World Series only once previously. To add to the significance of the day, this game would be the final Austin appearance for Bibb Falk, the legendary Longhorn coach who was retiring at the end of the 1967 season.

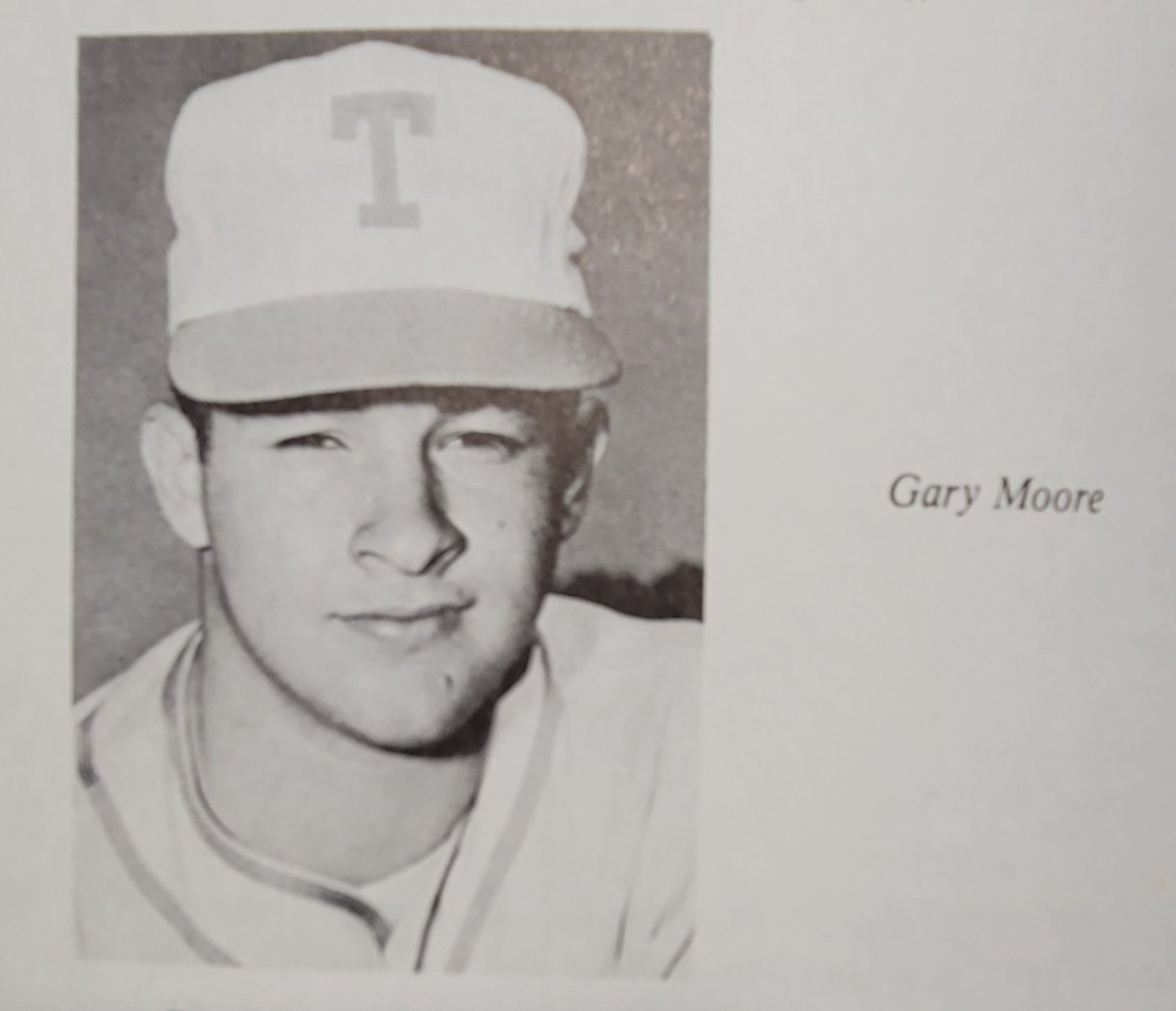

The 1967 Longhorns were not expected to be preparing for a playoff contest. Picked to finish in the second division of the Southwest Conference, Falk told the media that he hoped for a .500 season. Gary Moore, a pitcher/outfielder and the 1966 team MVP, had signed a professional contract with the Dodgers. His defection left the pitching to Tommy Moore, a hard-throwing senior righthander from Austin, Gary Gressett, a soft-tossing senior lefty from Mississippi, and a whole bunch of nobodies. I was one of the nobodies and was headed into my senior season in 1967. Pitching was expected to be a serious problem for Texas.

My UT baseball career prior to my senior year can be described as bad luck and bad pitching. I was a relief pitcher in the eyes of the coach, and to understand the role of a relief pitcher on the Longhorns in 1967, one must understand the rules governing SWC baseball at that time. The small schools dominated the Southwest Conference because simply put, they could outvote Texas and Texas A&M. Consequently, the SWC did not allow fall baseball practice and strictly limited the number of games any team could play. In 1967, for example, UT played 25 regular-season games, and West Coast teams often played more than 50. Because of the limited number of games, Coach Falk would use three pitchers predominantly two starters and a reliever. If the reliever failed in his first appearance, he went to the back of the line to wait his turn for another chance. Often, that second chance never came.

In 1965, I did well in my first opportunity, and I became the first pitcher to be used out of the pen. After getting a save against TCU, bad luck struck. Coach Falk broke my jaw hitting grounders to our shortstop while I was pitching batting practice, and although I did not miss a day of practice with my teeth wired together, he did not put me in another game.

Bad pitching struck in 1966. My first appearance was a disaster, and I went to the back of the line to become a little-used righthander for the rest of that season. My first opportunity in 1967 was against Oklahoma with the bases loaded and no outs, and I struck out the side without allowing a run. On the strength of that performance, I became the relief pitcher, and I pitched well enough during the season to maintain my position as the playoffs began.

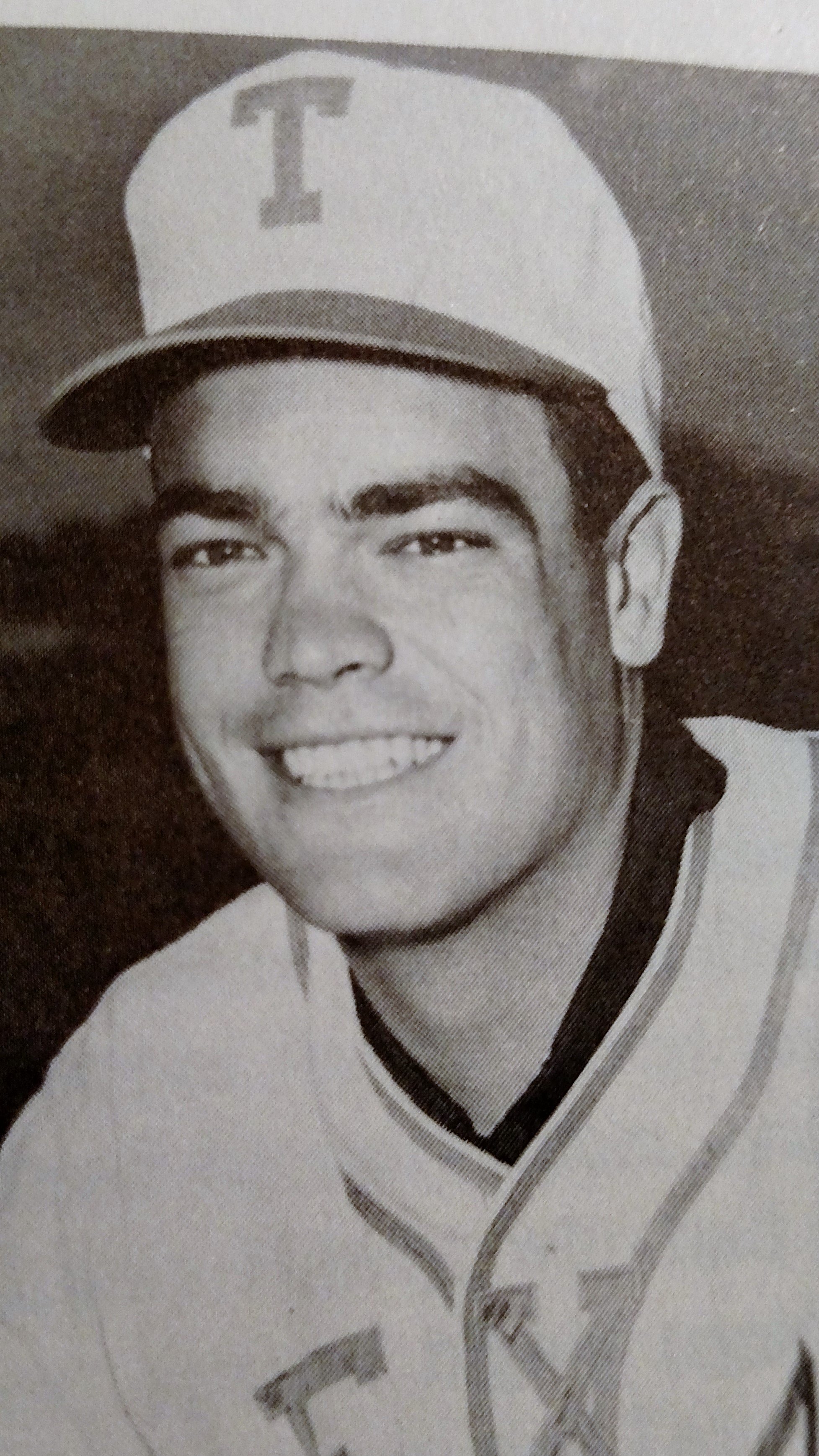

Led by senior pitcher Tommy Moore, who finished at 9-0 and received All-SWC and third-team All-America honors, the 1967 Longhorns surprised everyone by finishing the regular season with a 16-9 record and a SWC co-championship with TCU. By virtue of its 2-1 season series win over TCU, UT advanced to the District Six playoff against Houston. The Longhorns boasted the SWC batting champion, first baseman Bob Snoddy at .392, and the team hit 24 home runs, which was the second-highest total in Longhorn history. Gressett, the number two pitcher, had an unlucky 6-4 record, but his 1.53 ERA, the lowest ever for a UT starting pitcher, provided effective support for Moore. Four Texas players received All-SWC honors. UH had a hard-hitting lineup with several players hitting near or over .300, led by junior left fielder Tom Paciorek. He was hitting well over .400, had a school record for home runs, and was first-team All-America. Both teams featured two-sport stars, which was not unusual for the era. Texas third baseman Minton White also played basketball, and Houston outfielders Bo Burris and Paciorek and first baseman Ken Hebert were outstanding football players.

My season, like the player, was pretty good but not great. I threw a sinking fastball, which Coach Falk liked, and I also had a good curve, an ok slider, an effective changeup and outstanding control. Going into the Houston playoff series, I had pitched the third-highest number of innings on the staff. UT baseball had not yet discovered the concept of closer and Coach Falk brought me into games to protect a lead and into games in which we were behind. I had pitched as few as ⅓ inning and as many as 4⅔ innings in our games. I had given up about a hit per inning, but I had walked only one during the regular season. I was happy and satisfied with my role. I was the relief pitcher for the SWC champs, and I knew I would pitch in important games. I could neither ask for nor hope for more.

Texas and Houston had split the first two games of the playoff series. The Cougars routed Texas ace Tommy Moore in the opening game in Houston; Moore faced nine batters in the first inning, retiring only two, and gave up five earned runs before being removed. The Longhorns fought back to tie the score at 5-5 to take Moore off the hook for his first loss, but UH quickly regained the lead on a home run by Paciorek. Houston pulled away to record an 11-8 victory. I pitched four innings in the middle of the game but did not distinguish myself. I issued my second and third walks of the season and, incredibly to me, I walked in a run. I gave up three runs, two of which were earned, but was the only Texas pitcher to retire Paciore on a towering fly ball that our center fielder caught with his back to the fence.

Two days later, the teams played in Austin. Coach Falk again started Tommy Moore, as everyone thought he would, and with a second chance, Moore pitched a complete game and shut down the Cougars on eight hits. The Longhorns won 5-1 to even the series, and immediately the media questioned Falk on his choice of a starting pitcher for the third game to be played the next day in Austin. Moore is it until further notice, Falk said, but in speculating which pitcher Coach Falk would select for the deciding game, the Austin newspaper mentioned virtually every pitcher on the UT staff except me. Gressett, the logical choice, had left his last start early with what he described as a sore shoulder. I was neither surprised nor offended by not being mentioned. Coach Falk viewed me as a three-inning pitcher, and I agreed with the sportswriter’s omission of Raup as a possible starter. I joked at the time that even if I were the only pitcher at the park, Coach Falk would start someone else.

With this background, UT and UH prepared to decide which team would be the District Six representative at the College World Series. During batting practice, I was engaged in my usual pre-game activity of mindless chatter and shagging balls hit to the outfield when I saw Coach Falk walking toward the group of players I was in. He came directly to me and handed me a new baseball, which is the universal symbol to designate the starting pitcher. Coach Falk walked away without saying anything, and I was struck deaf and dumb by the realization that I was going to be the starting pitcher in the most important game of our season and of my life.

I immediately thought of my Dad, who was traveling to Port Arthur to attend to his ailing father and who would not see me pitch. There were no cell phones in those primitive days, of course, and I could not even tell him my exciting news. My on-again, off-again girlfriend was mad at me, as she often was, and was not coming to the game. Of those persons closest to me, only my mother and my brother would be present to witness whatever thrills or disappointment resulted from Falks unexpected decision. Throughout his storied career, Bibb Falk had defied the odds successfully with his unconventional decisions, but none was more surprising than his choice of me as the pitcher to start this game. I retired to the locker room to compose myself for the biggest game of my life.

I have never been more nervous than I was warming up in the bullpen prior to the game. Nervousness sapped my energy and made me feel weak and as though I could not get the ball to the catcher. Warming up was always like this for me, but once I got to the mound and into the game, the nervousness disappeared immediately. Coach Falk came into the bullpen and stood by the catcher to watch me throw. I finished my warmup routine and started toward the dugout to get ready for the game to start. Coach Falk approached me, and I expected a go get em or some similar words of encouragement. I should have known better. What he said was Go as hard as you can for as long as you can, and don’t embarrass anybody out there. Then the game started, and I was on the mound.

The tricks the mind plays are funny. As readers who stay with this piece will see, I can remember clearly almost every pitch in the 9th inning, but I remember very few details about the rest of the game. The Austin newspaper called my game one of the most magnificent pitching performances in recent years by a Longhorn, but I do not remember the game that way. I remember that I was not nervous and did not think of the importance of the game once I began to pitch. I remember that I was just pitching and getting them out. I remember that I used all my pitches, as a starter does, rather than throwing sinker after sinker as I did as a reliever. I remember that I had uncanny control of all my pitches and that I believed I could throw the ball through the eye of a needle. I remember a four pitch walk to a weak hitter that I could not fathom and an umpires bad call at first base that robbed us of a double play after the walk. I remember that we scored three runs early and should have scored six or seven. I remember that I was in total control of the game and that my dominance seemed like the most normal thing in the world.

Then came the top of the 9th inning. The Longhorns were ahead 3-0, and over the first eight innings, I had given up two hits, walked two and struck out four. No UH baserunner had advanced past first base, and I had faced only 28 batters. As I began my warmup pitches, the announcer reminded the overflow crowd that Bibb Falk was coaching his final game in Austin, and the announcement was the first I had thought about his retirement. None of us on the UT team believed this would be his last game, and we were in the College World Series as soon as I got three more outs. I was not tired, and I knew I would get those three outs as easily as I had gotten the first 24. When I finished my warmup pitches, I was relaxed and merely pitching a baseball game as I had been doing since I was nine years old.

Ken Hebert, the Cougars first baseman, tried to bunt his way on, but I threw him out for the 25th out. George Cantu, the third baseman, popped up to our shortstop, and I had 26 outs. Tom Paciorek, the hitting terror of the series, would make the 27th out that would send us to Omaha. He had come into the game with seven hits in nine at bats, but he was 0-3 as he stepped in.

I can see the 9th inning pitches as though I have them on video in my mind. Paciorek was taking a strike, and I threw a fastball right down the middle for strike one. Down in the count 0-1, he lifted a high, lazy foul fly down the right field line.

Our right fielder, George Nauert, was a catcher but played the outfield because of his hitting. Coach Falk did not use defensive replacements, and Nauert could not get to the foul fly from his alignment in right-centerfield. Paciores would-be third out fell harmlessly to the grass, but the count was 0-2, and I had him.

My next pitch was a slider that was maybe an inch or two outside. The plate umpire was John Mazur, a local postman who had called balls and strikes for my games since Little League. When he called the pitch a ball, I thought Mr. Mazur, after all these years, you owed me that pitch. The count on Paciorek moved to 1-2, and I still had him. Our catcher called for a changeup, and I made a mistake in my approach to the pitch. I loved his pitch selection because I had fooled Paciorek badly with a changeup during an earlier at bat, but when I accepted the sign, I thought Just don’t bounce it. Of course, with that negative thought, I bounced it at his feet. Paciorek was fooled and out on his front foot, but the pitch was too bad to swing at. The count was 2-2.

James Scheschuk, our catcher and my senior classmate, called for an up-and-in fastball, and I put the pitch exactly where he called for it. The pitch jammed Paciorek severely, and he fisted a slow roller down the third baseline that I could not field.

Our third baseman, Minton White, was an outfielder playing third base to get his potent bat into the lineup, and he was playing very deep behind the bag. His all-out charge to make the play was too late, and Paciorek beat the throw for an infield hit.

At the moment the umpire signaled Paciorek safe at first, I remember an immediate but brief feeling of fatigue. Perhaps the spell had been broken, but the 27th out was still there to get in the person of Bo Burris, the Cougars lefthanded hitting right fielder. After a swinging strike, Burris lined a single to left field moving Paciorek to second base. Ronnie Baker, the second baseman, moved into the batters box. Baker, a righthanded hitter, wasted no time. My first pitch was a slider headed for the outside part of the plate, and he leaned over the plate and hooked a low liner down the left field line. Paciorek and Burris scored easily, and as I returned to the mound with a one run lead to protect, Baker was on second, and Falk was on his way to me.

My first thought was No! You cannot take me out of this game now! He could and he did, although for a brief moment I thought I had talked him into allowing me one more hitter. I received a standing ovation as I left, but that was no consolation for me at all. Moore and Gressett both were warmed up and ready, but Coach Falk inexplicably allowed the pitching coach to send in for the save a reserve third baseman who had a great arm but who had pitched only 8⅓ innings all season. On a 3-2 pitch, the reliever walked the Cougars shortstop, Art Toombs, who was hitting under .200, and again on a 3-2 pitch, gave up a two-run triple to the next hitter. Gressett came in to retire the side with one pitch, but I had a no decision, and we were down 4-3 with only three outs to go. The Longhorns rallied valiantly in the bottom of the 9th, but our 27th out was the tying run thrown out at home plate to end simultaneously the game, our season and Bibb Falks coaching career.

Unlike the smack-talking and disrespect that todays athletes direct toward opponents, the 1967 Longhorns and Cougars met in the center of the field to congratulate, commiserate and wish each other well. Several of their players were gracious to me in victory; Paciorek put his arm around me and told me that he was happy to win but sorry to have ruined the great game I pitched. I appreciated their sportsmanship, but our loss crushed me. The game was my last as it was Coach Falks last. I grew up in Austin dreaming of playing some sport for the Longhorns, but now with the opportunity to put my team into the College World Series, I failed to get the 27th out with but a single strike to go. I had only thrown three pitches following Pacioreks infield hit, and now my time as a Longhorn pitcher was over. The suddenness and finality were shocking.

The teams parted and went on to their respective destinies. UH lost badly in the first game of the double elimination College World Series, but as they did on May 19, the Cougars fought their way back in the tournament before losing to Arizona State in the championship game. UT baseball season ended that day, and I and the other seniors graduated and began our futures. My future was high school coaching initially and then law, and I have been reasonably successful in both careers. Tom Paciorek, my chief protagonist, had an 18-year career in major league baseball as a player and then 19 more seasons as a broadcaster. No doubt we both are satisfied with our lives after our brief encounters with one another, but I wonder if he ever thinks about the deciding game in 1967. I certainly do.

With the perspective of forty years that included many years in coaching, I realize that Coach Falk made the correct decision to take me out. He never expected me to be in the game in the ninth inning, and Houston had just gotten three consecutive hits to narrow our lead to 3-2. There are many what ifs to ponder without that decision being one of them, however. I could have and should have had Paciorek out three times in his final at bat. What if the umpire had given the hometown pitcher the benefit of an extremely close pitch on 0-2? What if Coach Falk had made a defensive substitution in right field to start the ninth inning? What if I had not had the negative approach and had not bounced that changeup? What if our third baseman had been playing behind the bag but not with his heels on the outfield grass? What if after Pacioreks hit, I had reverted to my customary role of reliever and had thrown nothing but sinkers?

The biggest what if of all is what if Coach Falk had used one of our top two pitchers to get the 27th out instead of an infielder who had a great arm but who rarely pitched? I never will understand why a Hall of Fame coach who had 477 career victories, 20 SWC championships and two national championships would allow a pitching coach to make the most important pitching change of the season. Coach Falk did, though, and he later provided the 1967 Longhorn team its epitaph with his final comment to the media as UT’s coach:Some days you try things and they work; other days you try and they don’t work. He never spoke to me about this game, either in the locker room after the game or in the many times I talked with him before he died, so I will never know what he was thinking that day as he walked to the mound to get me.

So, readers who are still here, is baseball a cruel game when a team is so near victory in a crucial game but cannot get the 27th out? After much serious reflection, I do not think that it is. Certainly what happened to the Longhorns and to me in the UH game was cruel, but what happened to Tom Paciorek and to the Houston Cougars was wonderful. Our opponents refused to give up and forced us to record all 27 outs to beat them. When we threatened to steal their victory with our rally in the bottom of the 9th, they got the 27th out. I was the one who could not get that 27th out, not some malevolent Game that cruelly denied me a victorious finish. I failed when success mattered most, and accountability for that failure must be with me, not attributed to some inanimate Game. If ones best is not good enough, congratulate the winners and move on; do not wax philosophical about a cruel Game.

With the perspective of years and experience, I think I gained much from the UH game that initially brought me intense pain. I learned that sometimes a player can be at his absolute best, but his best still is not enough to overcome the opponent. I learned to respect opponents who fight their hardest to avoid defeat, no matter what the final outcome may be. I learned that no one is entitled to victory or to success, no matter how much he may want to win or how hard he may try to succeed. I learned that losing is every bit as much a part of the Game as is winning and that the final outcome does not diminish the accomplishments of those who competed.

Most important, I learned and believe earnestly that there is no disgrace or dishonor in failure if one has tried his hardest to succeed. Disgrace is giving less than one’s best effort or allowing failure to kill ones will to compete. True success lies not only in victory but also in picking oneself up after a gut-wrenching loss and in striving to be better the next time. If sports fans could understand how difficult victory is to attain and how much competition requires of players bodies and minds, appreciating a team and its players for the quality of the competition will be more rewarding than focusing on final scores. Perhaps then despicable epithets like choke to describe a losing effort never will be uttered.

No, baseball is not a cruel game, despite the occasional elusiveness of the 27th out. On the contrary, the Game allows both teams an equal opportunity to win and requires the winner to get all of the 27 outs. The Game rewards those who do more when victory or defeat hangs in the balance, and the Game penalizes those who fall short in those situations. Whether one succeeds or fails when all can be won or lost is the essence of competition. The Game benignly provides a stage to determine a contest’s outcome, but the Game does not guarantee any player success or compel his failure.

We lost on that fateful May day in 1967, but the Game was not to blame. Today I recall those events with twinges of regret and disappointment but with great pride in my performance. I failed to get the 27th out, but that day I was the best I ever was. On May 19, 1967, the stakes were high, and the competition was magnificent. The Game promises no more, and I was fortunate to have been a part of that competition.