By the early 1960s a majority of students favored integration both on the playing field and off. In May 1961 the Regents received a Student Assembly and faculty petition with 7,000 signatures to support “the immediate integration of all housing and athletic programs.” A concurrent petition from students opposing integration contained only 1,300 signatures.

As it turned out, the university’s first black varsity athlete would be in track, not football. James Means, an Austin high school student, planned to attend UT in the fall of 1963 and wanted to participate in track. His mother, Austin civil rights activist and teacher Bertha Means, called Frank C. Erwin Jr., who was then a new member on the Board of Regents, to protest the fact that her son was ineligible for varsity track only because he was black. A few months later, the Board voted unanimously to integrate athletics, stating that extracurricular activities would be open to all students without regard to race or color.

Back in the 20th century, the Southwest Conference (1914-1994) was one of the premier college athletics groups in the United States. Schools included the Universities of Arkansas, Texas, Texas A&M, Baylor, Texas Tech, Texas Christian, and Rice, and Southern Methodist. In the early days, my own alma mater Oklahoma was in that group. Football was king, and still is though the conference has melded into the Big 12 a few years ago , and the evolution of college conferences continues at a mind boggling rate. However, over fifty years ago the Southwest Conference was also burdened with the stigma of segregation in its enrollment and coincidentally with the lack of the diversity in its athletic teams. Hispanic athletes may have participated to a limited extent, but the line was clearly drawn regarding descendants of former slaves. Wanting to confirm this statement about Hispanic athletes at UT, I wrote to Ricardo Romo. See his reply at the end of this posting.

In 1963 Lyndon Johnson, a native of Texas, became president in the aftermath of John Kennedy's death, and Johnson began making integration of the nation a believable option for all citizens. At the Texas Relays in April of 1962 there were freshly painted-over signs in the football stadium that had promoted segregated washrooms. Johnson's daughters were students at the University of Texas at that time, so when I witnessed those painted over signs, it was understood that those things could no longer be allowed to exist with an administration committed to a path toward civil rights and freedoms.

This story about the first African American athlete to play in a Southwest Conference athletic event comes from David Webb, a retired attorney from Houston, Texas, who was on that team. He writes about his teammate James Means who was that athlete who stepped forward. Following David's account I have added the 'official story' of that time, as published in Know a University of Texas Online Journal.

UT Track, James Means 1st to Integrate the SWC, 50 Years Ago

by David Webb

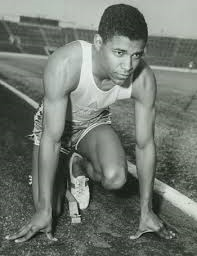

On February 29, 1964, James Means came out of the blocks in the heats of the 100, 200 and led off the UT sprint relay (as he then did for four seasons) at a very cold weather meet in Amon Carter Stadium in Fort Worth. This marked the first participation in a Southwest Conference event by a black athlete. If you hear it said or written that Jerry Levias of SMU or John Westbrook of Baylor were first, it is not so. Westbrook was the first football player in a game, Levias was the first football player after him, and a star, but both first played in 1966, almost 3 years after James Means. Several witnesses to this, in addition to me, are copied on this email.

James was also a star. He steadily progressed a from a 10.2 walk-on sprinter to 9.5 in his fifth year, after taking off the 1965 season because he felt he was not making progress. The next year, James was both the first black at Texas to earn a scholarship and the first to then become what we used to call a "Letterman." James ran 9.5 his senior season in 1968 and narrowly missed 1st in the SWC 100 that year. In 1969, he ran on the U.S. Army sprint relay, leading off for Olympians Mel Pender and Charlie Greene.

This is the guy for whom the "James Means Spirit Award," given annually to a track /field athlete, was named. He was my roommate on the track trips for the three years our seasons overlapped. When I called him today to congratulate and reminisce, I asked if any UT Coaches or Staff spoke to him in the Fall of 1963 about any issues or if he was was ever hassled about race by any teammate, other schools' runners or fans. He said no. It apparently happened that smoothly in track and UT was, not early in all things, but in this, was first.