Linus Baer through the eyes of a 10 year old

Childhood memories of the Christmas season stay with you. This one is seared into the personal brain files. The sounds of the Ronettes' new version of "Sleigh Ride" and Brenda Lee's already classic "Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree" formed the soundtrack in my ears and visions of something like sugarplums and the prospect of the Texas-Navy Cotton Bowl danced in my head on the last day of school, a glorious two-week break just hours away.

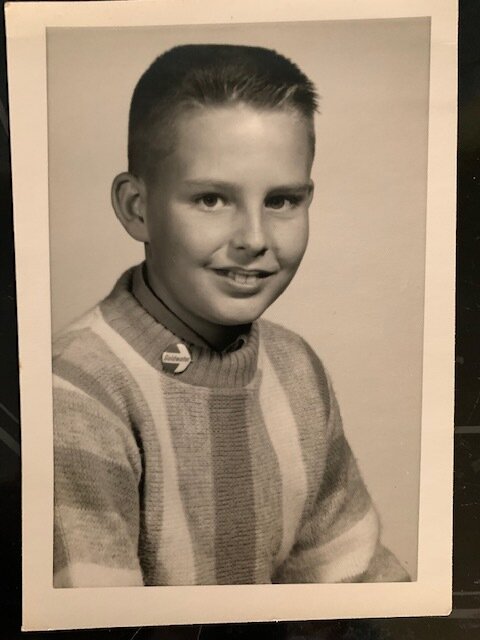

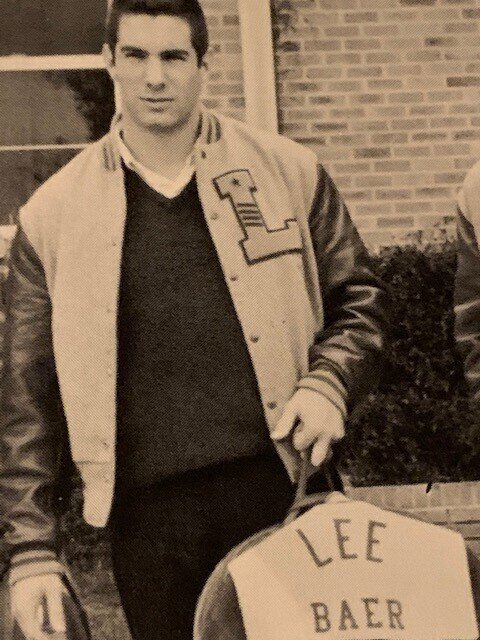

My fellow fifth-graders of Mrs. McGuire's class were about to go into our room, when what to my wandering eyes should appear... It was as if this striking, flat-topped, teenaged god of San Antonio high school football had descended from Mount Olympus. And he was gliding down the hallway at Jackson-Keller Elementary School. We stood in awe, watching as the almost fictionally-named Linus Baer effortlessly toted two giant six-packs of Coca-Cola under each muscular arm. The Texas High School Player of the Year was delivering Christmas party goodies to his sister Suzette's sixth-grade classroom this early morning in the waning days of 1963. We had been alerted to the tidings of comfort and joy, and stood reverently, eyes wide, some mouths agape. Christmas had come early, it certainly seemed.

Linus Baer vs. Warren McVea - One of the best football games in the history of high school sports.

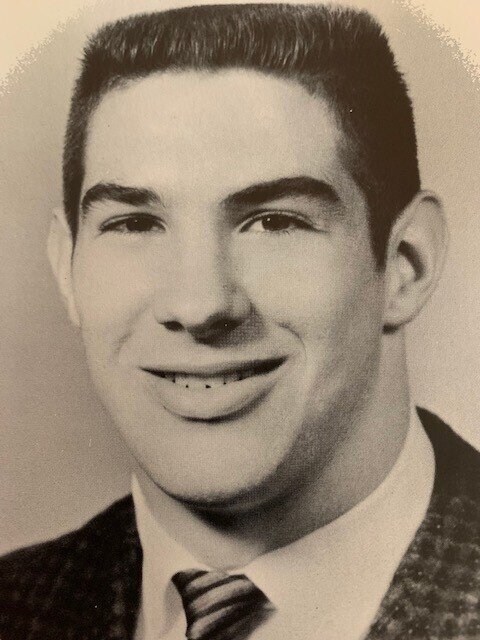

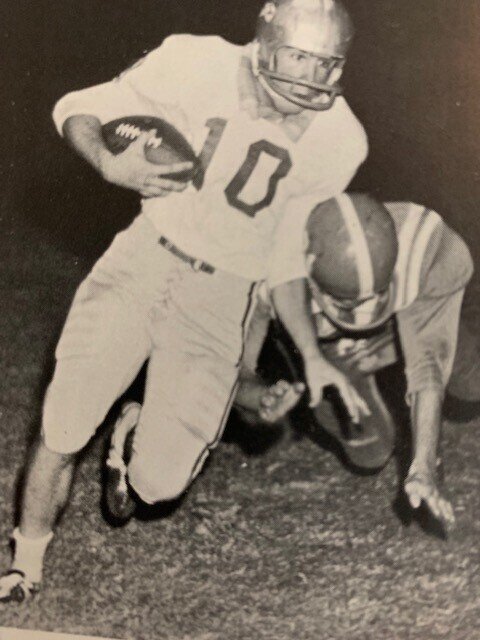

All football season we had witnessed the sensational feats of Baer as he ran, caught passes, punted, kicked, and played nifty defense for the Robert E. Lee Volunteers en route to an 11-0 start that finished with a narrow two-point loss in the state quarter-finals. Baer had merited all-district honors even as a freshman, so he had been on the radar of top college programs for several years.

Just three weeks earlier, Lee and Baer had challenged "Wondrous" Warren McVea and defending state champion Brackenridge High in the bi-district round of playoffs, to decide bragging rights for the city. On November 22, scarcely six hours after President John F. Kennedy had been killed by an assassin in Dallas, Baer and the Vols had taken the field against arch-rival MacArthur High to try to finish a perfect regular season and certify a playoff spot. It was a different time in America, in sports, in society.

I was there in the stands with my young friends, as Lee drubbed Mac, 50-12, with players and fans subdued by tragedy, still carrying on in somewhat dazed capacities. Even as a nation mourned, demand for tickets to the Lee-Brack matchup was so great that fans began camping overnight and waiting in line almost 18 hours before seats went on sale the next week. Twenty-three thousand tickets were all gone quickly and the water cooler talk and wagers in San Antonio's icehouses, office buildings and barbershops began to elevate expectations to stratospheric heights.

The two spotlighted teens, Baer and McVea, were used to competing against each other in track meets and reigned as the flashiest runners in the entire state. McVea had an edge in flat-out speed but either would've been hard to tag inside a cramped VW Beetle, and Baer, at a sturdy 185 pounds, could also overpower would-be tacklers.

The three daily newspapers in San Antonio, the Express, the Light and the News, had been drooling over the prospect of the Baer-McVea duel all season, and crammed pages with Lee-Brack facts, photos, stats and hype that week. One local TV station feverishly promoted an evening program to air the night before the Friday night game -- set for 11/29/63, one week after the assassination -- that would be a half-hour special titled "Great Runs by Baer & McVea." Another TV station had wisely already secured the rights to televise the marquee contest.

San Antonio was a charming old city, teeming with history and personality back then. Still is. But this was pre-HemisFair '68, pre-Spurs and long before the 24-hour sports cycle brought constant news of all pro and college "news," 365 days a year. The Alamo City, back then, was sometimes still referred to -- either affectionately or derisively -- as the world's largest small town.

Linus Baer and Warren McVea were celebrities in a quite populous American metropolis. I remember a class field trip to the SA Symphony downtown at the old Municipal Auditorium that autumn. The hostesses from a southside high school, Burbank's "Orange Jackets" were ushering us in when they politely asked where we attended elementary school. We knew our school's name wouldn't ring a bell so we billed it as "right across the street from Robert E Lee." The response from the girls was immediate and enthusiastic: "Oooh, that's Linus Baer's school," they cooed. Then, "He's cuuuute." ."Yeah, he's the best," we chimed. Such was the fame of young Linus Baer.

When Friday night, the 29th arrived, I was like tens of thousands of frustrated SA football fans. I had no ticket to the biggest game ever, so thank God for TV coverage. But luck occasionally finds the, well, lucky, especially among kids. Enter Mike Mahan, my bosom buddy. Mike's dad happened to wield the feared "board of education" as principal of Brackenridge High, as principals all did at their respective schools. He was a man of influence, but especially in this week, of all weeks. And so it was that Mike and I, two excited ten-year-olds clad in blazing red shirts to support the Lee Vols, accompanied Brack's tall, formidable principal as uninvited guests to the warm, roomy press box, high atop Alamo Stadium.

That evening, somehow exceeding Texas-sized expectations, McVea scored 38 points for his team, while Baer -- running, returning kicks, catching passes, and placekicking --tallied 37 of his own. One of his touchdowns was a 95-yard return, the only time either team kicked off deep, foolishly as it turned out, to the opposing school's star. Lee scored last, and the Vols were 55-48 victors, de-throning the state champs of '62. There wasn't a punt in the entire contest. Long before the term "instant classic" was coined, people knew that history had been made. Game films were even shipped overseas to entertain American troops in southeast Asia and Europe. Each decade, Dave Campbell's Texas Football magazine would hail the game as the state's best ever, and it stayed that way through the 20th century.

Warren McVea

Two months after the masterpiece game, McVea, a hotly-sought national recruit, chose not to play for an already integrated Big Ten team. He opted to stay closer to home and make his mark with one of the South's only football programs willing to sign its first black player in 1964. (Writer's note: McVea would star for the Cougars and played five seasons of pro ball. He was a member of the Kansas City Chiefs' Super Bowl IV champs. He was later convicted of various crimes and served several stints in prison before being released for good in 2000. In 2004 McVea was inducted into the UH Hall of Fame and has reportedly turned his life around. He is also a member of the Texas High School Sports Hall of Fame and the San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame.)

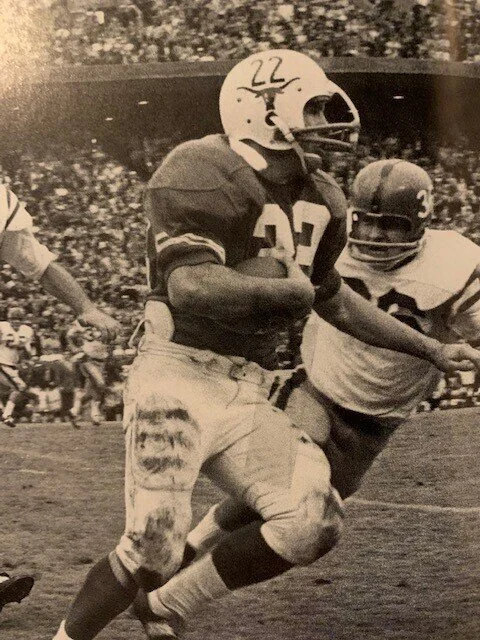

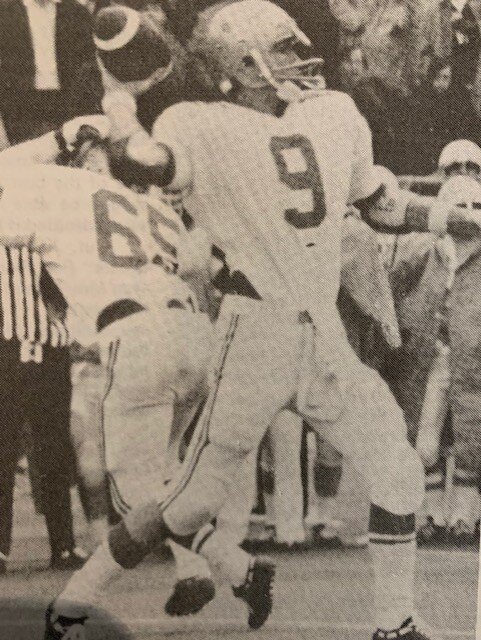

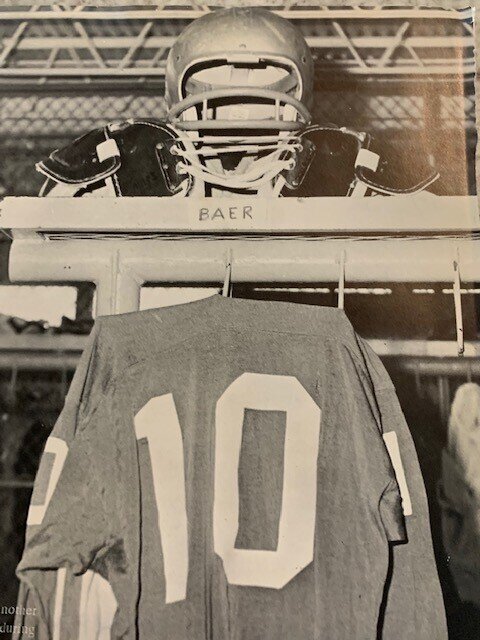

Linus Baer as a Longhorn

Linus Baer and Joel Brame

Linus Baer, bluest of blue-chip football stock, signed in February with Darrell Royal's national champion University of Texas Longhorns, fresh off a convincing 28-6 win over Heisman Trophy winner Roger Staubach's Navy team in the Cotton Bowl. It would be understated to say that the Horns were bullish on Baer. So highly regarded a recruit was he, that Texas later chose to play its Orange-White spring game at San Antonio's Northeast Stadium, Lee High's home field that it shared with MacArthur. Try THAT one on as a tribute to a high school signee. If it wasn't that, well, consider it a very, very, very mind-boggling scheduling coincidence.

But before Baer could even set foot on the Forty Acres for fall practices and classes in Austin, fate took a cheap shot at his football fortunes. That summer of '64, while playing in the then-prestigious, but ultimately still meaningless, North-South Texas All-Star game, Baer severely injured a knee. It was not yet the prime era of sports medicine and astounding six-month recoveries from horrific injuries. Baer's future on the gridiron was uncertain. Linus would have surgery (it would require removal of cartilage and repair of the medial ligament) and re-hab the knee while his fellow freshmen played their standard five-game season. The varsity missed back-to-back national titles due to an incomplete pass on a two-point try (losing to Arkansas 14-13) but later beat the already declared national champion Alabama team in the Orange Bowl and finished 10-1.

When September was peeled back on the '65 calendar, Baer was a starter at halfback for UT. He scored a TD in his first game as a Longhorn, the opener against Tulane, and also made waves with a 52-yard punt return. Against OU a month later, Linus delivered 48 yards rushing on ten carries, to aid considerably in a 19-0 spanking of the Sooners. But Baer's repaired knee didn't feel the same.

Gene Powell, Loyd Wainscott , Linus Baer and DKR

"It definitely affected my ability to move laterally," Baer told me almost 20 years after the injury, when I interviewed him for a book I wrote on the history of Robert E. Lee Vols football. "I still had pretty good speed straight away, " he continued, "but when I tried to make cuts off that leg it was like slow motion."

The 1966 season saw Baer, recognized by UT coaches as the best blocker of all the backs, moved to fullback. He flourished there his final two seasons. There weren't many carries but Baer opened big holes for HB Chris Gilbert with steady effectiveness. Gilbert would race for more than 1,000 yards in both years behind Linus, and would eventually become college football's first player in NCAA record books to compile three one-thousand-yard rushing seasons.

It wasn't in the bum cards dealt out for Baer to play in the glorious '61-'64 UT era (40 wins, 3 losses, one tie) or to explode in the wishbone's '68-'70 debut (30 wins, 2 losses, one tie). Instead, he and his Longhorn mates played in the three straight 6-4 regular seasons from '65-'67 that marked the only prolonged slump of Darrell Royal's two decades in Austin.

The Horns' lone bowl outing was a victory over Ole Miss in Houston's Bluebonnet Bowl game. But Baer wasn't one to look back at the gaudy statistics he compiled, game after game, back at Lee, as the most coveted football player in the Lone Star State. He later said he ranked those accomplishments behind what he contributed while wearing the famed burnt orange. "I'm proudest that I started three years for The University of Texas and I that I was a captain my senior year," Baer told me. "That's voted on by your teammates," he explained, pride in his voice.Linus also received the sportsmanship award and the leadership award at the Longhorn team banquet after his senior season.

Allow this writer, this fan, another vivid memory. A good seventh-grade buddy's dad (those kinds of connections!) was a member of the Oak Hills Country Club in San Antonio, and got us in to watch the 1966 Texas Open golf tourney. We had a blast, following crowd favorite Chi Chi Rodriguez around the course, listening to him banter with fans, picking up his busted tees and discarded Tiparillo cigar butts while appreciating seeing-eye putts and rocket-like tee shots.

But we got our biggest thrill when we cut through the manicured course between holes and spied the great Linus Baer, strolling with the gorgeous girlfriend he had met at Lee and would later marry. We gathered our courage, sprinted over and asked for Linus's autograph. He had performed these duties, amazingly as it sounds now, after almost all his high school games at Lee as a senior several years earlier, always mobbed by adoring kids, girls and grown-ups. Baer was used to it, and smoothly, politely obliged us, while pretty JoAnn beamed. Linus had the easy bearing of a regal movie star twice or three times his age.

For three youngsters, the presence of the world's best golfers suddenly had dimmed. Golf had again taken its rightful place way, way, way behind football, even on a sparkling spring day with September four and a half months away. We cared now not a whit that Harold Henning of South Africa was about to walk away with the Texas Open trophy and a paycheck with lots of zeros. We had again seen Linus Baer, up close. And we owned fresh autographs. Howard, Irl and I couldn't stop smiling.

After football

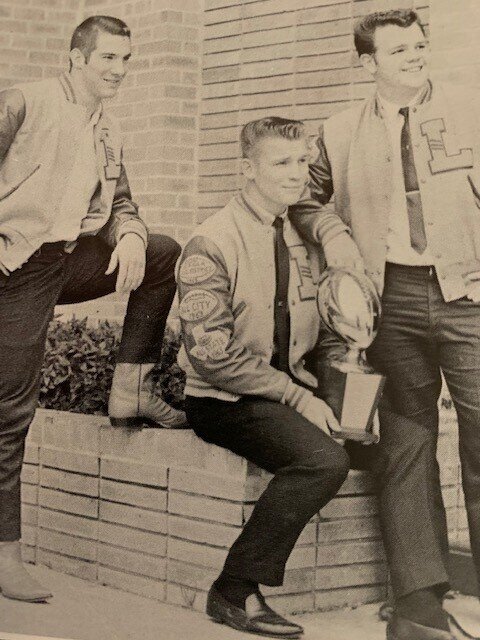

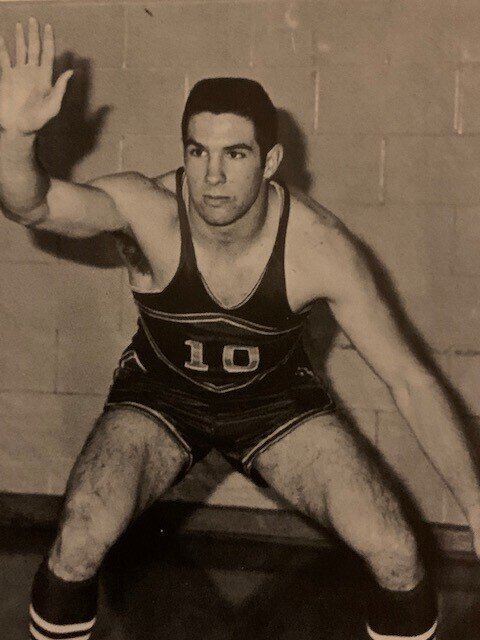

After Baer's UT playing days, he rapidly climbed through the ranks of the Houston and San Antonio business communities. He was a bank vice-president back in the Alamo City by his late twenties and would navigate a long, successful career in finance and investments. Naturally, Baer was elected to the Texas High School Football Hall of Fame and the San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame, keeping company there largely with former Spurs and San Antonians who made it big in the NFL or major league baseball. It says something that those honorees, for the most part, earned national recognition, Olympic gold, lucrative contracts in professional sports and big-time product endorsements. Linus Baer had been a four-sport star at Lee High and became the greatest schoolboy football player in the greatest state one autumn before turning in a respected career at UT.

Pardon the cliche, but looking back almost six decades, Linus Baer was truly a legend in his own time. As a teenager, he gracefully faced and no doubt relished intense fame and pressure while collecting honors and accolades that can scarcely be imagined now for the times in which he played. Unlike the sometimes stereotypical "high school hero" whose life peaked at the age of 17, Baer never had to look back to those days, just as he never -- except when he spontaneously waved a low "come on, catch me" hand at a trailing Jefferson High Mustang -- had to look back at outclassed opponents in futile pursuit.

Nobody was gaining on him. Nobody would catch him. That's not to say Baer's post-playing days have all been easy. He lost his wife, JoAnn, the former Lee and Texas cheerleader, to cancer when she was just 39. And nobody knows the assorted struggles of any individual. But Linus Baer, it would appear, has continued to excel at life, the way he did in athletics.

The Story of San Antonio Lee sports dominance

Back in Baer's senior season, Lee High was in only its sixth year of existence and just it's second competing in the state's highest athletic classification. Baer, as mentioned earlier, was the Texas Player of the Year, the first of an incredible four Vols to win that award in a ten-year span from '63-'72.

Tailback Pat Sheehan in '65, WR Richard Osborne ('71) and QB Tommy Kramer ('72) followed Baer as honorees. In an era of only the district champion advancing to the state playoffs (four teams now advance from each district), Lee produced six teams that reached the state semifinals or better in 13 years. The '65 and '69 squads lost heartbreakers in the state finals. One edition, the '71 squad, beat Wichita Falls, 28-27 for the title trophy, avenging a loss to the Coyotes two years before.

The '71 championship contest was the first high school game played in the Cowboys' Texas Stadium in Irving (similarly, Lee had won the first high school game played in the Astrodome, beating Beaumont Hebert in a semifinal duel in '69). Kramer was firing bullets and bombs to Osborne and Pat Rockett, a UT football signee who then took the first-round draft money from the Atlanta Braves and played several seasons as an MLB shortstop before arm injuries ended his baseball days. Osborne was beefed up to play tight end at Texas A&M, then spent four seasons in the NFL with the Eagles and Jets. Kramer was an All-America QB at Rice, later starting for a decade with the Minnesota Vikings, earning Pro Bowl recognition.

But revered as they were, none of Baer’s successors at Robert E Lee High achieved Linus legendary status with teammates, fans, future students, and a generation of football players.

- Write to Larry Carlson at lc13@txstate.edu