“Click on the text denoted in red font on the side bar to visit other sites in this “article” grid

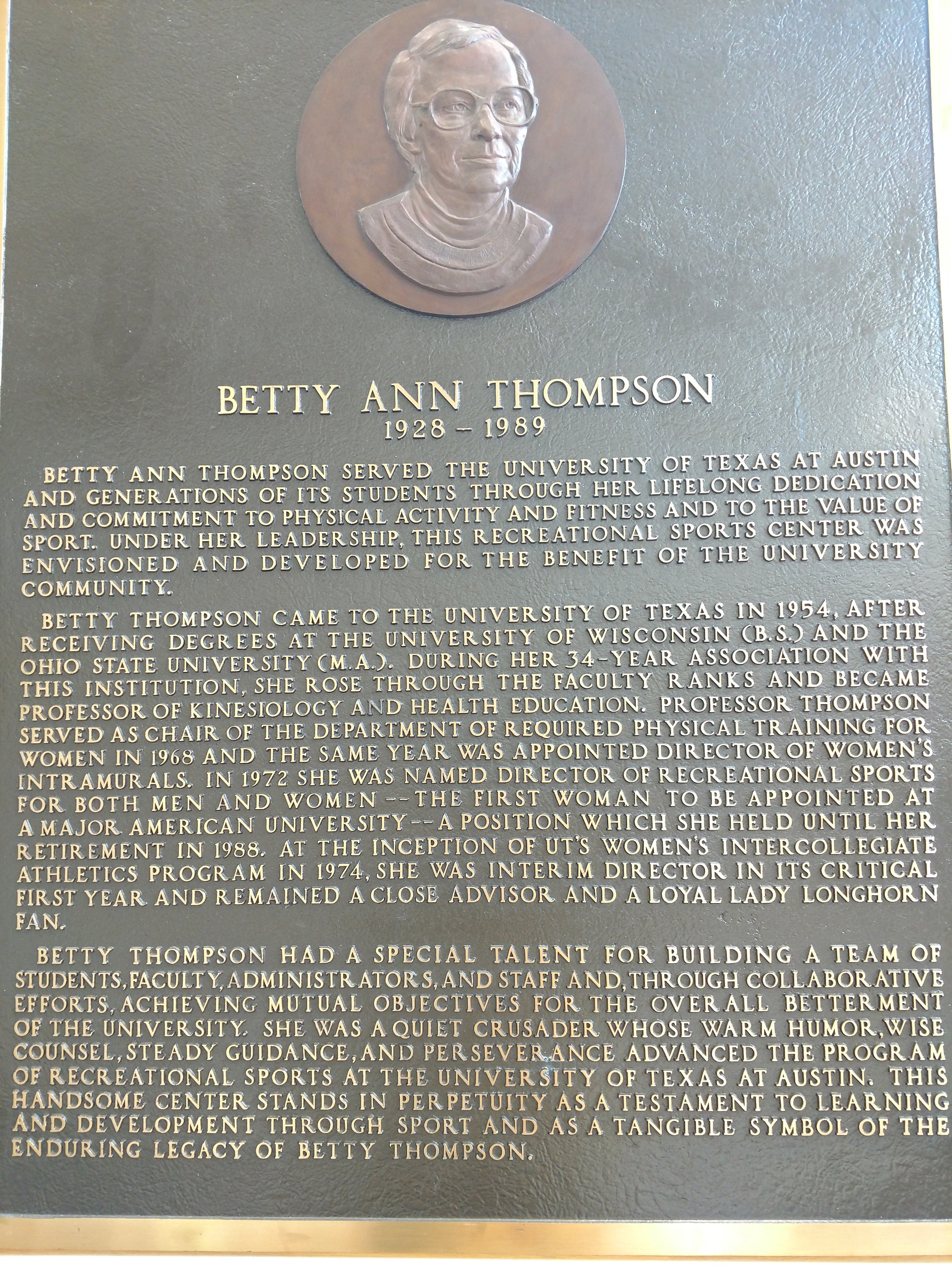

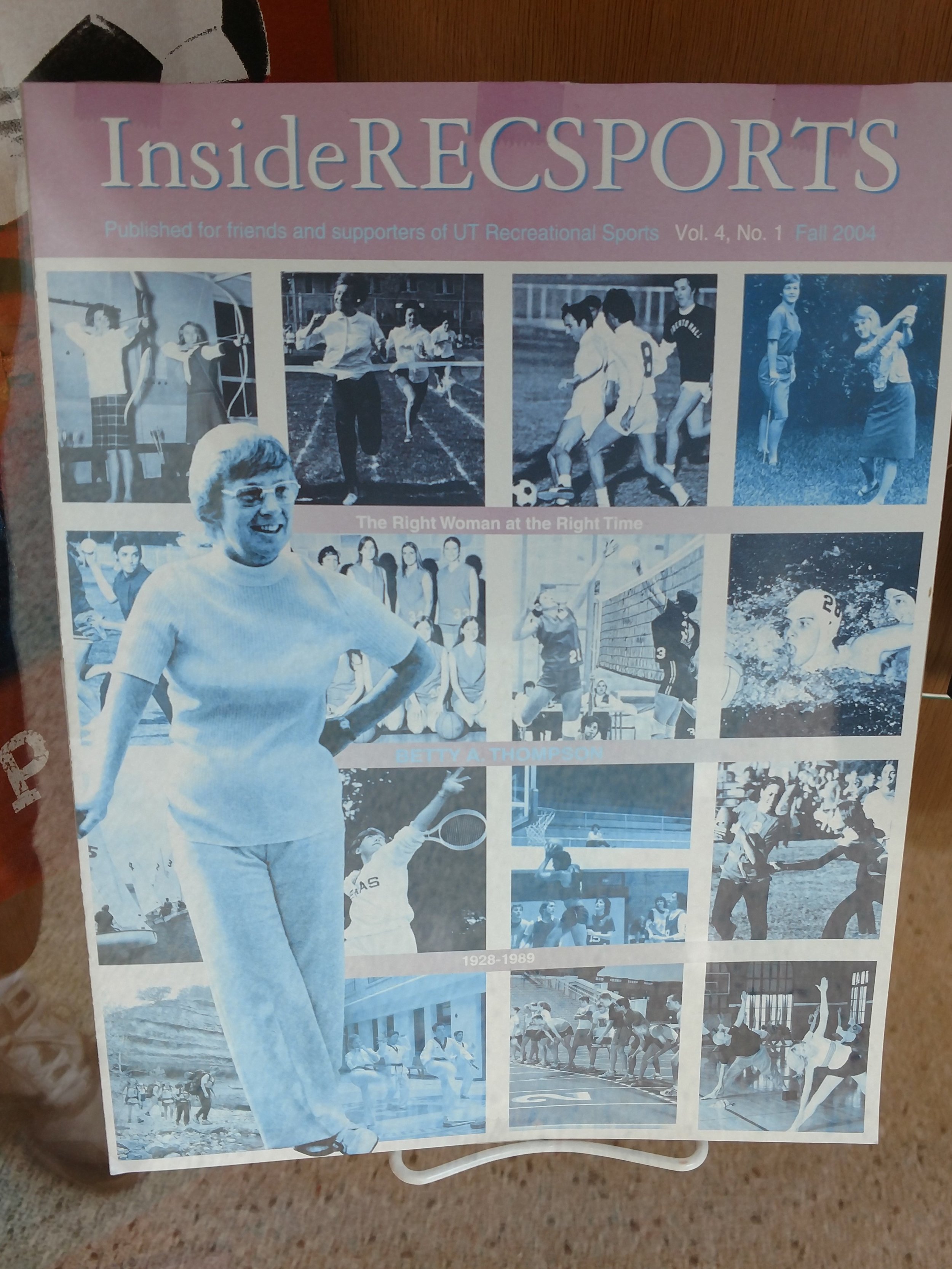

Betty Thompson, "The Quiet Crusader" sets the tone for the transition from the Hiss doctrine to the Lopiano Renaissance.

Betty Thompson's thoughts about women in sports were closely aligned with Anna Hiss. Like Hiss, her primary passion was recreational sports. Regardless of her beliefs and the other key administrators disdained for the male sports model, she understood that many female student-athletes wanted UT to add an intercollegiate sports model component that copied many of the features of the men's program. The student-athletes got their wish.

1966-1967 basketball and volleyball are the first two women's intercollegiate sports to be added at UT.

1967-1968 badminton, golf, and gymnastics were formalized as intercollegiate sports

1968-1969 tennis is recognized as an intercollegiate sport

1969-1970 swimming becomes an intercollegiate sport

The total budget for the seven varsity women's intercollegiate teams was $3000.

1973-1975 VERY IMPORTANT YEARs FOR LONGHORN INTERCOLLEGIATE WOMEN SPORTS

In addition to the title of Intercollegiate Sports Interim Woman's Athletic Director, she was also the Director of Recreational Sports responsible for the merger of the men's and women's intramurals. In 1975 she moved all administrative functions from Anna Hiss Gym to Gregory Gym Annex. Betty Thompson's accomplishments as Director won her the Babe Didrikson award for Best Athletic Department in 1975 and 1976.

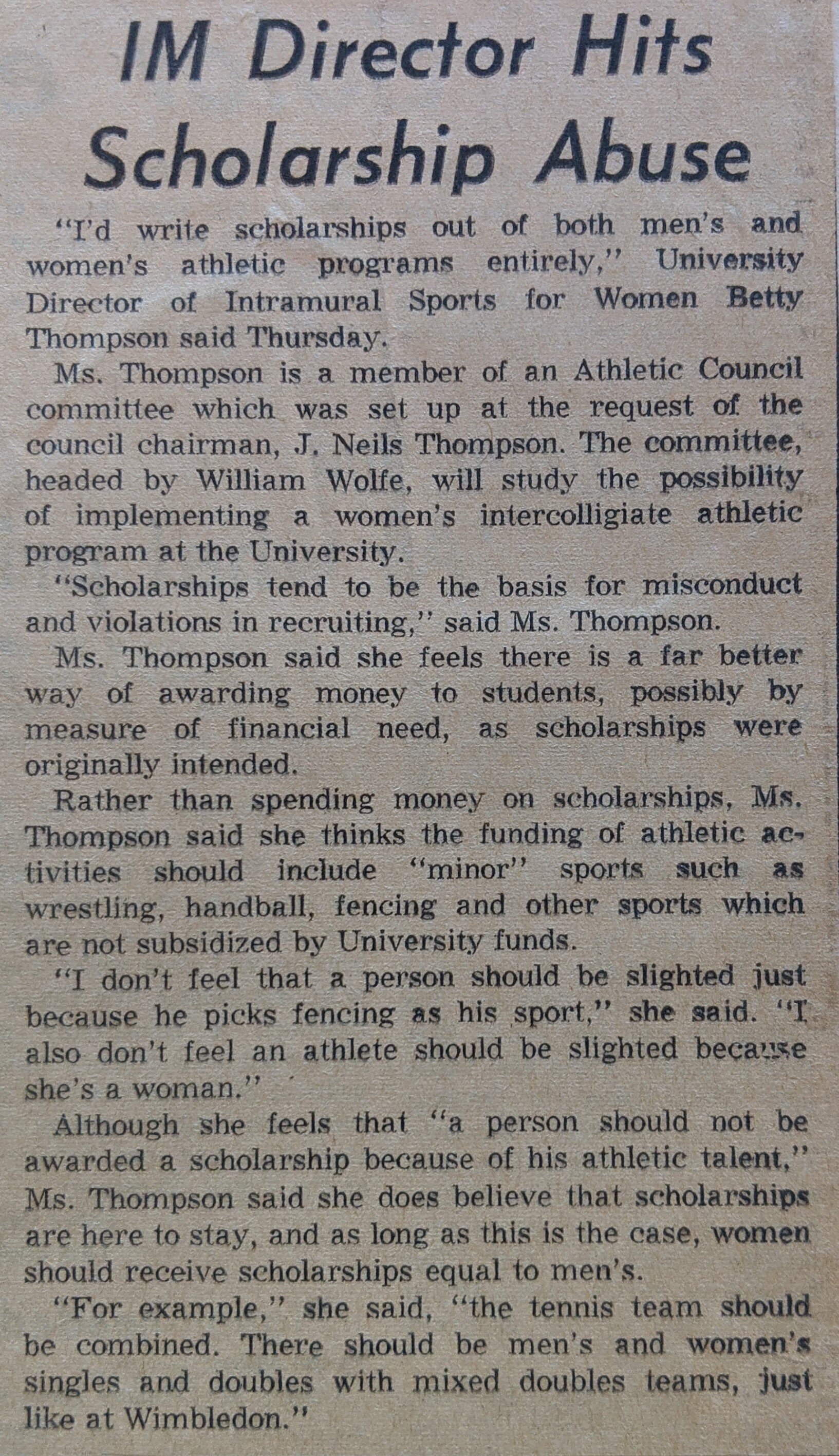

Betty Thompson "NOR HELL A FURY LIKE A WOMAN SCORNED"

On March 11, 1974, Betty Thompson wrote a letter to Dr. Stephen H. Spurr questioning the Athletic Councils (all Men) deciding on a program for Intercollegiate athletics for women. The letter was sent after Spurr rejected a special committee’s recommendation to merge the women's and men's programs into one athletic department. Instead, the Athletic Council suggested a "separate and distinct" department for intercollegiate athletics for women. On the surface, this decision appeared to guarantee the independence of women's sports from men's sports, but in reality, this decision made the success of the new intercollegiate women's athletic department problematic. Without question, funding from scratch and building a Women's Athletic Department would require tremendous sacrifices from both the players and coaches.

This letter was sent after Spurr rejected a special committee’s recommendation to merge the women's and men's programs into one athletic department. Instead, the Athletic Council suggested a "separate and distinct" department for intercollegiate athletics for women. On the surface, this decision appeared to guarantee the independence of women's sports from men's sports, but in reality, this decision made the success of the new intercollegiate women's athletic department problematic. Without question, funding from scratch and building a Women's Athletic Department would require tremendous sacrifices from both the players and coaches.

A TRIBUTE TO BETTY THOMPSON FROM RODNEY PAGE

It was 45 years ago, during the summer of 1972, that I first set foot on the University of Texas campus. Little did I realize how that would affect my future, personally and professionally. It was also my first visit to Austin, TX. I came to interview for a teaching position in the Department of Physical Instruction, which later merged into the Department of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation (HPER).

The first person I met on campus was a calm, soft-spoken, selfless, bespectacled Dr. Betty Thompson, who was representing the Physical Instruction Department. Betty wore many hats, which included Physical Instruction, Recreational Sports, and Women’s Athletics. We met in her office in Anna Hiss Gymnasium. In our first meeting, it was apparent that she was genuine and trustworthy, and I sensed she was a person that I could trust. That never changed and actually grew.

After my first year of teaching, I approached Betty Thompson about the possibility of coaching the UT Women’s Basketball team in 1973. Rice University in Houston, TX, had offered me a teaching position, but I wanted to remain at UT, particularly if I had the opportunity to coach women’s basketball. I served as a graduate assistant women’s basketball coach at the University of Houston during my Graduate studies. When the UT coaching position became available, I approached Betty Thompson about applying for the position. It’s important to know that not many people were lined up to apply or coach the team. It was like going to battle with limited resources. Perhaps you had to be half crazy to even want the job. I guess that described me, particularly since there was no pay the first year, and we were on the ground floor of establishing a legitimate intercollegiate basketball program. It was truly a labor of love and passion.

Betty Thompson hired me first as a teacher and then the UT Women’s Basketball coach. As I reflect on those early days, I remember Betty Thompson as a friend, mentor, guide, and advocate. In offering me opportunities as a teacher and then a coach, I always saw genuine acceptance in her eyes. She saw the best in me, she believed in me. I felt valued as a human being, and I always heard the truth in her voice. What a gift to a young “man of color” stepping into the reality of the social landscape of the time and the state of UT in terms of diversity and inclusion. I often think how easy it would’ve been for my UT experience to have never happened. Yet, it is history.

Being the first African-American head coach was never discussed. It was never brought up when I was offered positions as a teacher or coach. I was hired based on competency rather than tokenism. This is not to say that race was not significant. It was definitely not in denial but more about understanding the social climate and the UT reputation and environment at that time. The social issues of the day were too obvious to deny, and UT was certainly not immune to them. What can be openly and freely discussed was not spoken so overtly in those days.

I’ve heard it said that sometimes “words unspoken speak loudest.” I feel confident that this was true concerning our relationship. I think that both Betty Thompson and I were listening to a voice that didn’t use words (Rumi). We both were aware of the issues of the time concerning equity, gender, and race. Looking back, it is clear that her actions demonstrated and spoke loudly about her commitment to equity and fairness. From my perspective, she was a champion in that regard. She had concern for my journey as a “man of color” every bit as much as I understood her journey as a woman, as we were both fighting for equity, justice, and equal opportunity. I cannot be persuaded otherwise. There is another name that comes to mind when I think of Betty Thompson, and that name is Branch Rickey. I’ll let those who know the history and story dwell on this connection.

Betty Thompson and I maintained a warm relationship based on mutual respect and honesty throughout my seven-year tenure at UT. As a friend and mentor, she provided sage counsel in personal and professional matters. Her strongest recommendation came as she offered candid suggestions for me to consider in response to my removal as UT Women’s basketball coach.

If I had the opportunity today to sit across a table from Betty Thompson, I would take her hand in mine and share a few heartfelt words. Betty, thank you for the opportunity to hire me both as a teacher and UT Women’s basketball coach. Most of all, thank you for believing in me and always seeing the best in me. Thank you also for your courage in hiring me. We both demonstrated tremendous courage in that venture. And last but not least, thank you for trusting me.

Our relationship sparked my dear friend Betty Thompson's genesis of a successful and fulfilling career for me that has continued into the present. I stepped into my destiny through the portal of our relationship. For that, I am eternally grateful.

In my own words and still standing,

Rodney Page

Life Coach/Consultant

June 23, 2017